Chaoyang Review 001: “A Nickelodeon Riff on Camus”

Reviews of: The new album from Xi’an post-punk band FAZI, a WeChat sticker pack that’s more picture book than reaction GIF, and a definitive ranking of Beijing’s (remaining) bookstores.

Tianyu: Welcome to the first Chaoyang Review. Here’s what’s within:

I

Close Reading: Emily compares bookstores in Beijing

II

Chinese Rock on Chinese Rocks: Jake Newby on the new FAZI (法兹) album

III

Contemporary Memes for Sad Comicbook Teens: Krish Raghav on WeChat stickers

I

Close Reading

Emily reviews Beijing's remaining indie-ish bookstores (as people in your English class). Tag yourself.

PAGEONE

“Trilingual influencer expat with a Nietzsche quote on his IG bio. Overdressed for school. Research interest is something niche af, like napkin-folding in the Early Renaissance or Victorian pornography.”

Emily: Once owned by the Singaporeans, PAGEONE was the coolest kid around the block. Large portions of my teenage years were spent in its double-storied landmark branch in Sanlitun, where shelves used to be packed with crisp “original editions” (原版书), meaning English books. PAGEONE also perfected the art of selling those decorative hardback interior design portfolios that plague every liminal coffee table in Beijing. It was The Bookworm’s stylish cousin from across the street (have you heard that it’s closed?).

PAGEONE Sanlitun has shrunk to half its size. The rest is an ARKET store. Original editions (or what’s left of it) occupy an inconspicuous corner. Young fashionistas coming for a night out would stroll in while they wait for their Didi pickup and leave upon the beckoning of a brave new world.

Rating: 7/10

3 for nostalgia, 3 for its current reserve of Chinese books, 1 for having my back when I run out of things to do in Sanlitun, waiting for my non-INFJ friends who are always late.

One Way Street 单向街

“Feminist NB cynic because they read too much. Have 4 different side projects outside of school including an avant-garde zine that has better print quality than professional magazines. Likes: 16th century satirists; Hosting dinners with friends from carefully curated backgrounds for intellectual exchange.”

During one of my visits to OWS I found myself in a high-brow literary salon…situation, and overheard some classic waffling about “hermeneutics”, “abstractism” and “disenchantment”. But, my newfound respect for them comes from their curation, in their Hangzhou branch, of a special stand for feminist books in support of The Chained Woman two months ago. The display reads “If we can’t remember everything, we should at least remember what we’ve forgotten”.

Rumour has it that the store got a call from the local police “inquiring” about the display after it went viral online. The next day, a new sign went up that said: “her story is inaccessible”. The pun was brilliant, because “inaccessible” (无限) also meant “unlimited”. There are countless Chinese women out there who fell victim to trafficking, forced marriages and rape, walking on a one-way street towards a set of chains. This store’s attempt at amplifying female voices for the sake of those women won me over.

Rating: 8

Mostly for being a staunch feminist, but also their merch——saving that for another episode.

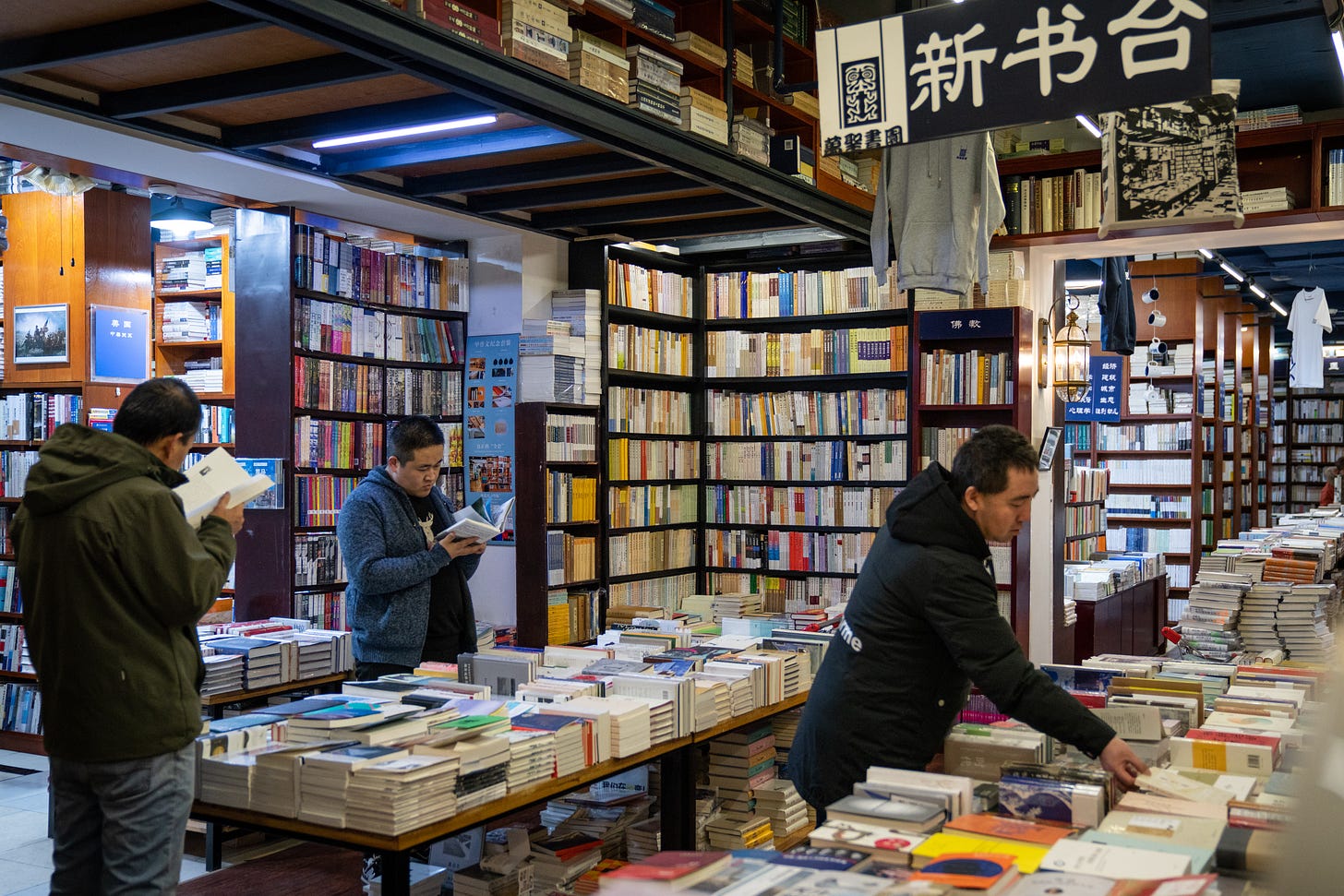

All Sages Books 万圣书园

“Regular attendee of One Way Street’s dinners. Quiet, likes to keep a low-profile, but secretly leads protests. Probably decolonizing the curriculum. Doesn’t text you back. Occasionally sends you links to journal articles on Foucault.”

I once spent an unproductive afternoon of dissertation writing in their cosy cafe, where One Way Street founder and host of renowned talk-show series “Thirteen Invitations” (十三邀) once interviewed Chaoyang Trap fave Luo Xiang. Drinks on the menu are named after book titles and (of course) I went for the “Submarine at Night” (an absolute must-read).

But All Sages is one of the few bookstores where the “cafe” isn’t the focus. It's a true book lovers’ mecca, with everything ranging from mainstream classics to the most obscure, undiscovered gems. Books are shoved together so tightly that it’s impossible to pull something out. It reminds me of my vintage bookstore hopping days in London and I physically couldn’t bring myself away from the shelves to sit down and write.

I later read that the founder of All Sages was an icon during the Tiananmen protest. That would explain the ever sobering and truly soul-striking slogan painted over the cashier: “Acquire liberation through reading.”

And thus I forgive their inadequate service and repeated hollering at customers for not wearing a mask. Government rules have to be followed, obviously. It’s the price to pay for liberation.

Rating: 10/10 for the spirit.

6.4/10 for service. (get it?)

Yanjiyou 言几又

“Double majoring in English and Visual Arts but gives zero shits about either. Only here for hook ups. Wears too much cologne, claims to like the Romantics, and steals pick-up lines from Shelley.”

This bizarre name comes from dissembling the Chinese character “设”, meaning “design”, and it’s apparent that their book selection process is a similar kind of mangling. The end result is an illogical mish-mash of a limited number of titles, often outdated and barely readable. The store, particularly its Guanshe branch, is (ironically) poorly designed, unevenly lit and has a confusing layout where the walkway cuts through a no-talking cafe area, and the children’s books section is also their…warehouse, with half-opened cardboard boxes.

As I write this review I wasn’t surprised to come across a Zhihu thread written by a former staff at Yanjiyou, criticising the chain’s lack of management and mistreatment of workers. Despite the ambition to open 100 branches across China, Yanjiyou was forced to close down many of its so-called “cultural lifespaces” in recent years due to its broken supply chain. Yet again I sigh at a cursed trope in contemporary China: a dying industry wears a facade of wanghong extravagance only to be pierced through by business basics, accelerating its own demise.

Rating: Compared to the first three bookstores in this review, 3/10.

Compared to Xinhua Bookstore, I’m willing to raise it to a 4, tops.

Sisyphe 西西弗书店

“Too optimistic about life to be studying English. Hates it when it’s too “gloomy” and prefers the jolly stuff, such as the idylls. Loves to share quirky facts: did you know the majority of Shakepseare’s sonnets are addressed to men?”

The store has nothing to do with the tragic figure it’s named after. It’s more of a Nickelodeon riff remotely inspired by Camus, mostly stuffed with benign gardening guides and a huge self-help section. More importantly, it sells the most original danmei—male-male romances—out of all the stores in this guide. I was surprised to find that a lot of the steamiest of these romances I first read online were vanilla-ed into “clean” versions for “commercialized copies” (商志), where homosexuality is toned down into homosociality. They’re shelved proudly next to The English Patient and Orlando and it’s always difficult to know how to react. I’m thrilled to see that an internet subculture can appear in a tangible form alongside canonical works, but I lament their unwilling collusion. They have come so very far to be visible, and yet what’s seen is not even what’s intended to be seen in the first place.

Also the coffee is decent.

Rating: 5/10.

11/10 for having danmei, -7 for mutilating it. +1 for the decent latte I had while I sulked about the mutilation.

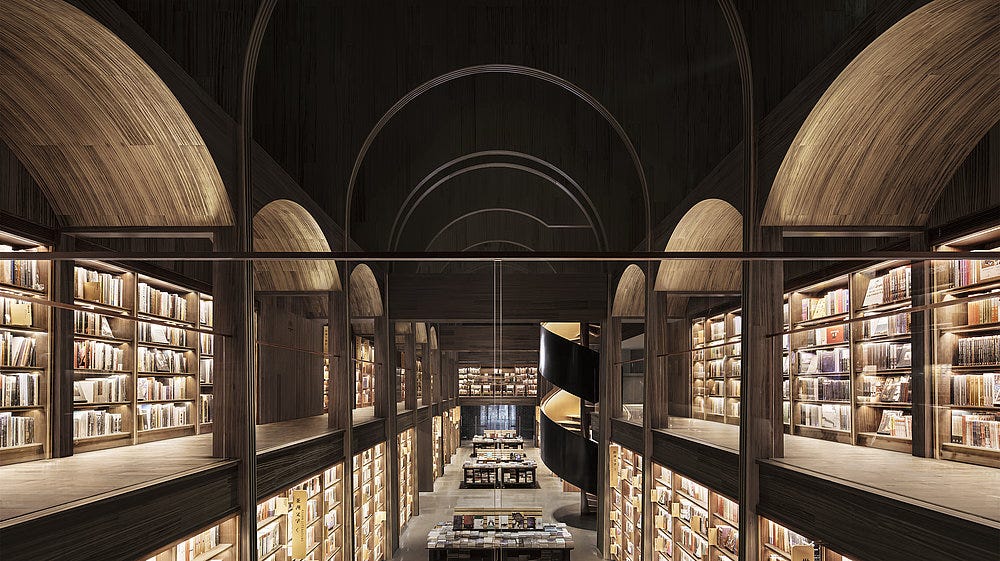

Yan: If I continue the English classmates comparison, all of the above (except for All Sages) are trust fund kids living rent-free in serviced apartments. They’re chains that have a parasitic relationship with shopping malls in exchange for favorable rent rates. Think Fangsuo Bookstore in Taikooli in Chengdu, and the wanghong Tsutaya bookstore in OōEli (天目里) in Hangzhou.

Krish: Many of these bookstore images also circulate frequently on Twitter on account of their flashy designs:

Yan: The codependency of book stores and shopping malls in Chinese cities is so common that it’s hard for me to think of a book store, besides All Sages, that’s not in a mall. But when I think about it, I’m actually less bothered by the malls than the chain. Living in a big city in China you unavoidably have to go to malls… a lot.

When bookstores become chains it takes away their personality and renders their curation less interesting. When it’s so easy to find and buy books online, I go to bookstores to browse, to be surprised, and to look for books that won’t be recommended by algorithms. Many chain bookstores have the vibe of an IRL online bookstore with a cafe and a stationary shop attached—everything is sleek and clean, yet predictable. On the other side of the spectrum, All Sages may have stuffed too many books on their shelves, but when certain books are presented at prime spots, you know you need to read it. I guess OWS’ chained woman curation was an exception, but we also have to take into account that the chain started as an indie bookstore, and its brand was closely connected to its founder Xu Zhiyuan, an influential “public intellectual.”

Caiwei: The growth of mall and CBD office building bookstores in China is not organic. It’s engineered to offer a “cultural experience” tied to corporate mission statements. The books are secondary. This is evident in how overpowering the gift and stationery sections always feel in a regular mall bookstore. Thanks to Fangsuo and Citic Securities (who own the Citic bookstore chain), every real estate giant feels compelled to create their own bookstore chain, or at least include a “cultural space” when mapping out their new developments. These bookstores sometimes feel closer to wanghong pseudo-exhibitions, co-opted by entrepreneurs and real-estate tycoons willing to pay lip service to the “culture scene”.

SKP, the luxury mall in Beijing created its own bookstore line Rendez-Vous in 2017, aiming to “provide new urban hybrid spaces in which all kinds of cultural business intermingle.” The mall, at the same time, is known for denying a delivery driver entry for wearing the yellow uniform that signifies his blue-collar status.

On the other hand, book stores like All Sages that put books and curation first, including my favorite Douban (no relation to the website) and now-defunct Yecao, usually live off a symbiosis with nearby universities. With online shopping eating into their popularity, a lot of them operate community WeChat groups to try new ways to shift inventory—I’ve found so many rare second-hand gems from Douban’s Wechat posts on my feed. Truly one of things I miss the most about living in Beijing.

Krish: Just going to drop this here for anyone asking about Beijing’s zine-centric Jet Lag Books or Post Post (I still love you):

Krish: Alright, Jake. Over to you!

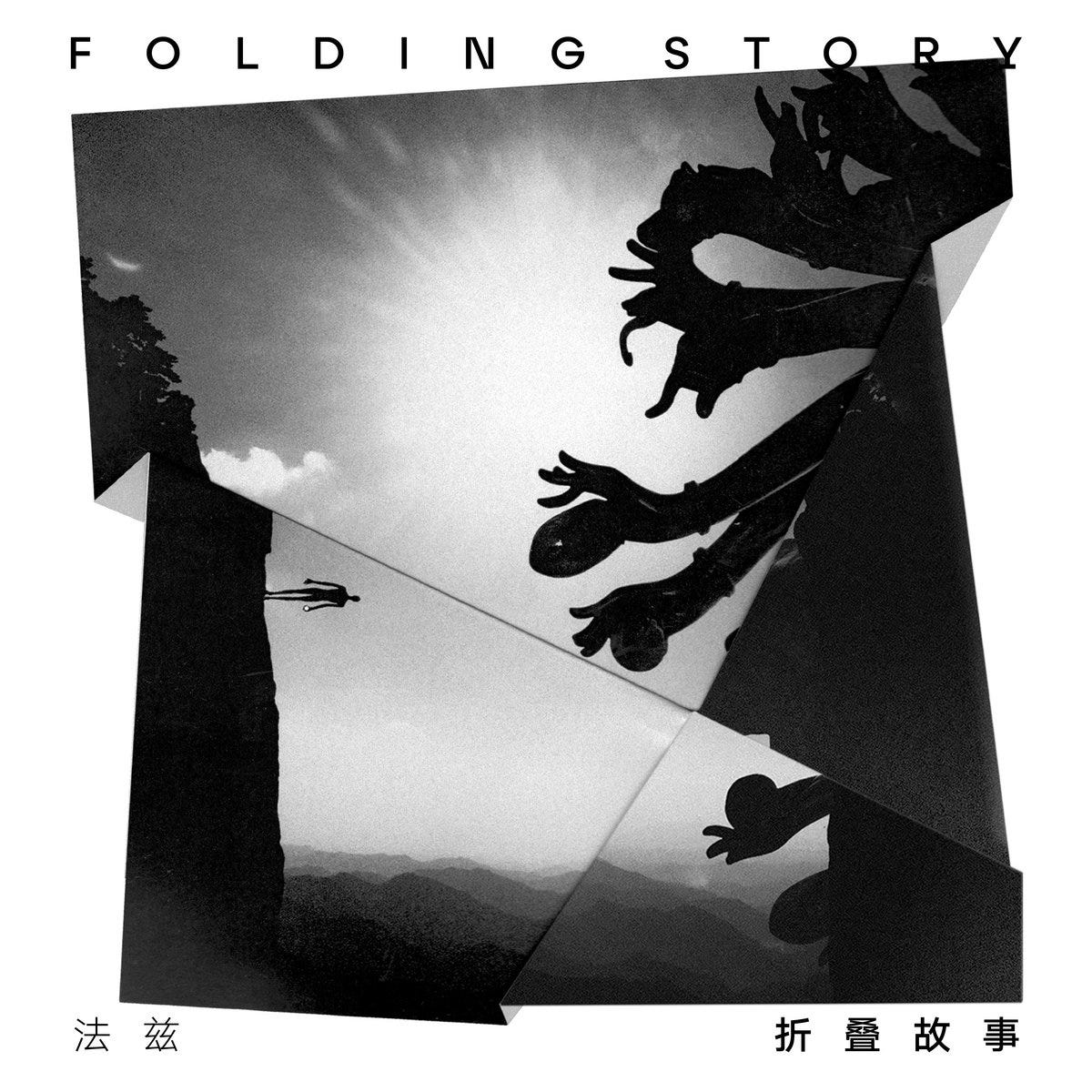

Jake: There were a few recent records that came to mind when I was asked to write a Chaoyang review. Wu Zhuoling’s down tempo electronica release Another Shore was one, Old Heaven Books’ experimental folk and rock compilation Encore 72 Hours was another. But FAZI’s Folding Story was ultimately the one I lumped for, partly because it’s so unexpected. It’s a fascinating, confident departure for the band. (Alas, it’s not, as I thought for a brief moment when I saw the title, a concept album based on Hao Jingfang’s Folding Beijing.)

II

Chinese Rock on Chinese Rocks

Jake Newby reviews the jagged, icy new album from Xi’an post-punk band FAZI

Jake: I like the matter of fact quote that FAZI frontman and chief songwriter Liu Peng issued as part of the promo for this new record’s release: “We’ve created a different self, a fresh FAZI. It’s worth listening to.” That’s maybe not the most inspirational of sales pitches (largely why I love it), but he’s right—it is worth listening to.

It's also worth watching. Emphasising that this is FAZI’s most ambitious effort to date, the band released the album in tandem with a short film directed by Jin Shien that runs for the record’s full length. Shot in Qinghai, southern Gansu and in the Qilian Mountains, it features some spectacular imagery. You should go watch it:

Formed in Xi’an in 2010, FAZI made their name with a post-punk sound laced with krautrock, best encapsulated on their 2017 album Heart of Desire. It was a no nonsense post-punk album, with bright guitar melodies layered over Cure-like basslines and some very Maybe Mars production: slightly rough and reverby, with a purposeful DIY edge. Folding Story is a very different proposition.

With the new album, FAZI have embraced clean and clear production. They’ve swapped Maybe Mars for Space Circle and the guiding hand of ‘godfather of Chinese post-punk’ Yang Haisong for that of Chinese post-rock pioneers Wang Wen (惘闻). Folding Story was recorded at Wang Wen’s studio, with members of the band contributing instrumentation; Wouter Vlaeminck, producer on Wang Wen’s most recent records, mastered the album. (Between Heart of Desire and this latest effort, there was even a baton-passing Fazi record: the instrumental Dead Sea featured Wang Wen leader Xie Yugang and was based on a Yang Haisong story.)

The shift to a more expansive, crisper sound—that ‘fresh FAZI’—is on display immediately. Album opener ‘Invisible Water’ begins with Liu’s sparse vocals over trickling water and piano parts. It’s a hint of what’s to come, a signal that a band once known as The Fuzz have jettisoned their fuzziness, even if it’s quickly followed by the ‘don’t worry we still make post-punk’ of lively second track ‘Eye in the Sky’.

The next section is where Folding Story falters slightly. ‘Beautiful Teeth’ returns the album to ballad territory, then ‘Never Say Forever,’ a sprawling lullaby, is followed by another slow number in ‘Silence’. The tracks are fine in and of themselves but the record hasn’t built a consistent atmosphere at that point and their combined effect is to suck some of the air out, or make you wonder if it’s on shuffle. ‘Never Say Forever’ in particular feels like an alternative album closer that they couldn’t quite let go of. The clarity of production also reveals its downsides here, bringing Liu’s lyrics into sharper relief, a scrutiny they don’t always withstand.

But then the album surges back into life for a rousing second half. ‘Body / Mind / Soul’ is a classic burst of post-punk and ‘Vigil’ strikes a darker chord while continuing to build momentum, before the final three tracks find FAZI at their best. The jagged guitars and shouted chorus of ‘Delingha’—a track that feels especially primed for live shows—lead into the driving ‘Died in the Wind’ and then ‘Way to Atman’, the album’s swelling closing track that comes awash with triumphant trumpets.

This last trio of tracks is also where the accompanying visual narrative feels most cohesive, helped not insignificantly by the sheer beauty of Qinghai and the Qilian Mountains. The central lyric in ‘Delingha’ about facing a cold mountain is inevitably portrayed literally, ‘Died in the Wind’ sparks a snow-top freak out and the end credits feel of ‘Way to Atman’ is complemented by the protagonist progressing to empty roads and open skies.

Folding Story is not without its flaws, but taken as a whole, it’s a bold move. After their (slightly awkward) appearance on the second series of iQIYI’s heavily commercialised The Big Band (乐队的夏天), it would’ve been easy for FAZI to capitalise on their new-found fame by rushing out a by-the-numbers album and agreeing to every festival booking that came their way (they would not have been the first of the bands who took part in the show to do so). Yet instead of choosing the 乐夏 formula they’ve taken the Bildungsroman route, following their independent-minded friends and occasional collaborators Hiperson in attempting an ambitious concept album. It doesn’t consistently hit the heights of that record but, in line with the theme at the heart of the album, FAZI have opted to try and take their own path.

RATING: 7.5 out of 10.

P.S.: If Chinese rock bands amid…Chinese rocks is something you’re into, here are a couple more options to cue up in YouTube: Stolen playing 3,500 metres above sea level in the Si Guniang Mountains and Tation undertaking a fascinating art project in their native Qinghai.

Simon: We’re far enough into the evolution of the music referred to as “Chinese post punk” that it is no longer as much of a matter of Chinese musicians taking inspiration from Joy Division and Sonic Youth, as the next generation of musicians trying to create new versions of P.K.14 and Carsick Cars. As Jake points out, you could chart FAZI’s journey as a movement from the lodestar of P.K.14 to that of Wang Wen. The aforementioned Chinese bands make wonderful music, and I don’t mean to imply that musicians need to have foreign influences, but I do wonder if there’s been an “involution” of inspiration in this particular scene, a gradual limiting of the palette available to artists. To my ears this album sounds like FAZI experimenting with some intriguing new textures and approaches, but then bolting these back onto the same template.

For example, the lumbering bass and spoken word-like vocals of “Vigil” caught my attention, reminding me of a certain sort of film or theater score. I found myself wondering if the track would defy expectations and continue as a dirge—it would be an interesting left turn to revel in amorphousness and make it compelling. But then, sure enough, the song locked into a drum pattern descended from the high hat-focused beat of mid-00s dance punk.

Post punk has already gone through enough revivals all around the world to be basically meaningless as a term, but I still love it, perhaps because of all the possibilities its legacy offers. Post punk isn’t reducible to just one particular streamlined form of guitar rock, but also warped dub, sedated psychedelic chanson, and grimy proto-techno… “Chinese post punk” feels increasingly cut off from other “post-punks” in terms of its reference points, production style, and the way in which bands are managed and operate as units. This relative isolation could be positive, leading things to evolve into a unique new direction in a few years, but right now the style feels very much like a given format, which to me FAZI push against but don’t quite manage to transcend in Folding Story.

III

Contemporary Memes for Sad Comicbook Teens

Krish Raghav reviews a new WeChat sticker pack that’s more picture book than reaction GIF

Krish: WeChat stickers are in the midst of an interesting evolution.

Their role has mutated beyond reaction GIFs and emojis. Like second-wave memes, they’ve become self-contained pleasures, conspiratorial coded archives of shared meaning. Stickers aren’t just simple pop culture reacts or conversational gambits anymore but…repositories. They’re a cultural archive. On Chaoyang Trap we called them a "Moodboard Industrial Complex."

Stickers are topical, reflecting controversies and serving as records of online wordplay, such as this recent example:

They can be showcases, portable portfolios of an illustrator’s style, often as complex as an animated short:

They can be bonding moments for fandoms, like this example featuring a chibi-fied music idol.

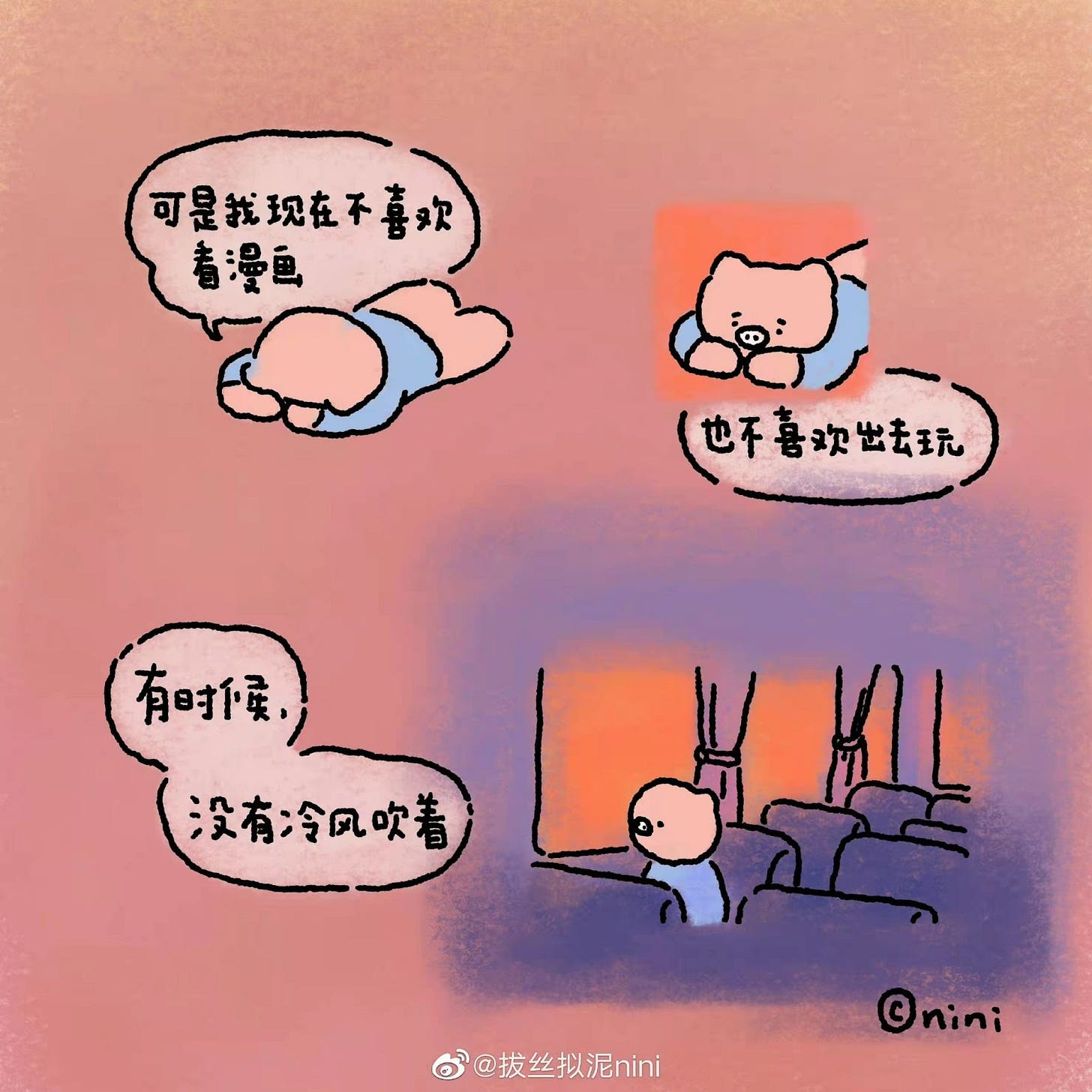

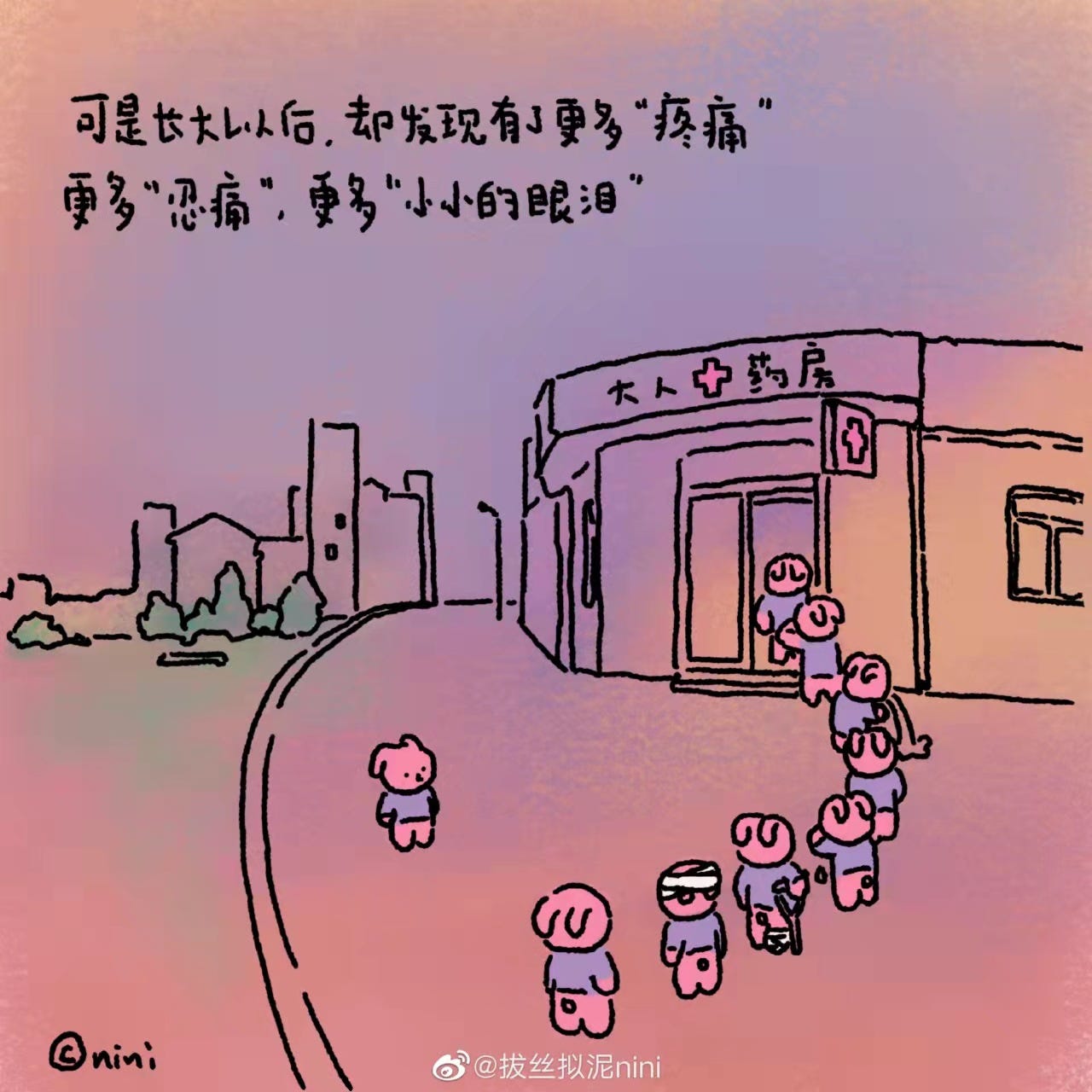

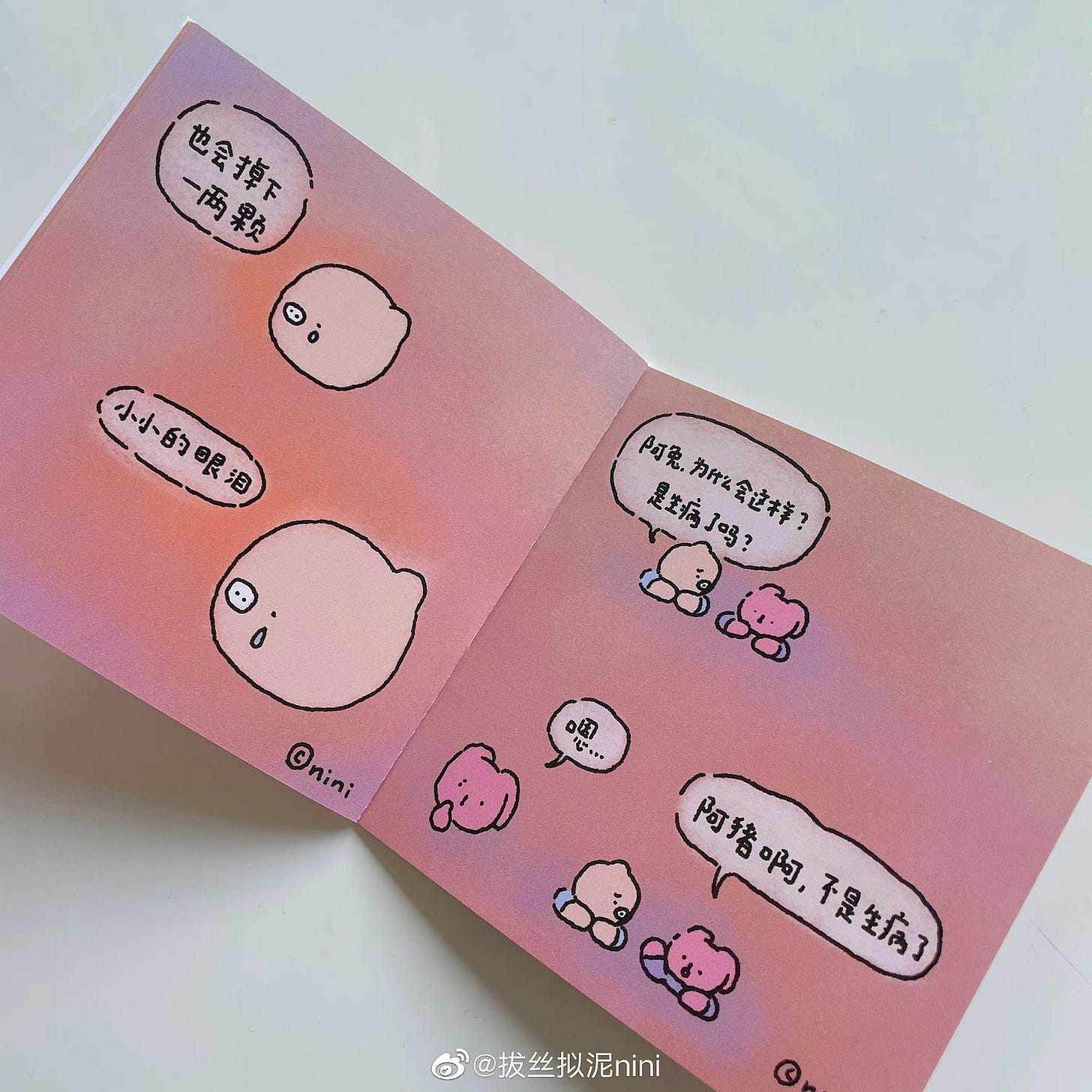

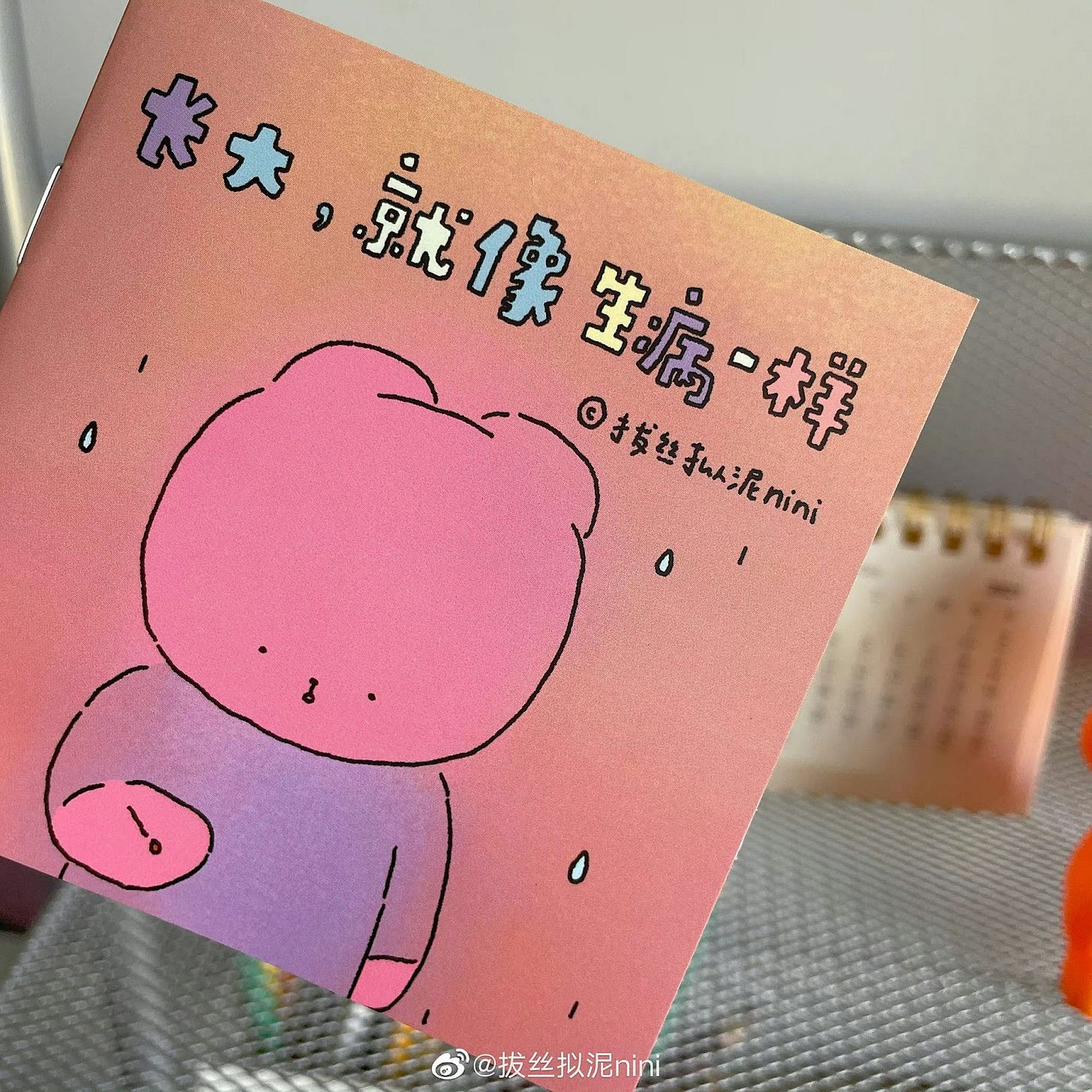

What I personally find most fascinating though is that they’re becoming storytelling devices, and a recent favorite is illustrator 拔丝拟泥’s (Nini) “阿猪阿兔一起玩” (“A-Zhu and A-Tu Play Together”), which uses the sticker form as a picture book.

Nini is a Chinese comic book artist whose work is a common fixture at art book fairs. The images in this sticker pack, like much of her WeChat work, are “repurposed” panels from a comic zine. Her work is best described as “cute tragicomic”—the titular pig A-Zhu, an omelet-flipping champion and returning character in her work, cries in almost every story, a victim of late-capitalist shenanigans like real-estate scams and game show disqualifications. Her style is a languid daydream, all mellow gradients and slapdash (yet somehow perfect) linework.

This source zine is titled Growing Up is Like Falling Ill, where A-Zhu and their rabbit friend A-Tu reminisce about childhood memories and compare adulting to a disease. The cultural touchstones here are familiar: a numb, “funereal” (丧) outlook on the future, and an involuted life experienced as permanent tiredness.

The sticker pack takes panels from the zine and remixes them with new captions. This new form lives solely on the WeChat platform, downloadable as a collection of 16 captioned images. It’s possible to read this merely as a “brand extension exercise,” an illustrator trying to maximize presence across different social media platforms. But the sticker pack makes no mention of the source zine, and is clearly meant to circulate independently of its source—a parallel version of the same images, functioning as fragmented stories in your own conversations.

Sticker / meme captioning is a uniquely recognized skill on the Chinese web, one often noticed as a "talent" just like drawing or longform writing. Sticker makers have to both capture a prevailing mood and offer expressive range, something this pack does particularly well. Note the combination of stickers below that allows for "progression" in mood or situation, a potent property in sticker packs that allows for sophisticated callbacks in conversations:

Others (like the snowman below) are harder to shoehorn into casual conversation, and function merely as a recognizable "Nini" image, an inside joke, a piece of affective flair.

A good sticker pack, then, needs to be "usable" as conversational fodder, AND foster a kind of micro-community, with the art style (and voice) signaling a mutual recognition of subcultural knowledge. This comes to the forefront in interest-based WeChat communities or company-wide work groups, where sticker choice and profile pictures stand in for the entirety of one's persona. The right sticker, deployed at the right time, functions akin to spotting a good band t-shirt or a tote bag joke.

As online phenomenon, it's a bit like feeling connected to diffuse communities around specialized meme pages like Classical Memes for Hellenistic Teens (appreciation of which signals your knowledge of The Classics) or the sadly defunct Facebook group Tractor Loverzz (appreciation of which signals your knowledge of tractors in Punjab).

This is one possible approach to a question I hope is asked more: how do you evaluate a WeChat sticker pack? "Craft" is far too subjective, as my favourites span everything from lo-fi scribbles to slick animations. Instead, I want to consider what you might call "circulatability"—how the give-and-take of particular sticker packs adds to what can be expressed on WeChat, and what can be expressed about us.

In Nini's case, it is our granular sadness, each of us unhappy in our own way, that finds endless resonance in her crying pig and lonely rabbit.

Rating: 6 out of 5 cry-laugh emojis.

████: I agree that the key, or really only, criteria for good stickers is circulatability. No matter how artfully produced, a sticker isn’t any good if nobody uses it. I think the most circulatable stickers, at least among my friends, tend to be a particular kind of cultural remix that takes some visual content and applies it in a new way - not just a reference or clever meme (though these are good too), nor like the overplayed reaction GIFs favored by boomers on Twitter that can be used for almost any scenario, but illustrations of a very specific feeling or concept in a fresh way. (This is an absurdly under-discussed topic worth addressing in much greater depth than a comment in an online newsletter but anyways here’s a sticker favored by my own micro-community:

Henry: I think it’s also worth disambiguating circulation’s quantity from its quality. How many people find joy in discovering 小众, unpopular stickers, the ones whose WeChat storefronts show a few dozen downloads or donations? Who doesn’t like swapping these with just two or three friends, with the “personal touch” of barter, where the sticker itself, its use value, has not totally been subsumed by its function as a token of exchange? Of course, one of advertising’s triumphs is its ability to endow corporate mascots with the intimacy of a close friend—cf the “You look like a good Joe” scene in Blade Runner 2049, in which the protagonist's seemingly one-of-a-kind virtual girlfriend turns out to be mass-produced—so maybe the feeling remains, even among company-wide chat groups. Like Ryan Gosling’s replicant character, I’d probably feel a jolt of pain and betrayal if I saw A’Tu and A’Zhu on the phone screen of someone I disliked.

Yan: I just learned about the concept of idiotism today, and I would like to think A-Zhu as the accidental 笨蛋-ism philosopher of our generation (see exhibits A and B below).

In one Nini comic, A-Zhu fails to win an egg frying competition because they believe the merits of a “sunny-side up” have nothing to do with elaborate performative cooking and styling, which I interpret as the refusal to turn a simple dish into a readily consumable commodity on social media. An intentional decision to withdraw from the game of late capitalism.

The underlying meaning of the stickers defines the affinity among sticker users. I’d be angry if not-good-at-capitalism A-Zhu stickers are used by… say, crypto bros.

Krish: That’s it for this crisp, short, 4600 word reviews piece! A reminder that we are open to pitches—send us your review ideas. Bye!

Jake is planning a 1,000-mile round-trip to go to a gig in a couple of weeks. It better be good.

Krish has a five-star rating on Goodreads despite publishing zero books.

Emily is heading to All Sages once the restrictions are lifted.

████ is a ███████ and ██████████ at ███████ in ████, and has a disturbing volume of stickers that he can’t share in this newsletter.

Simon is dealing with Beijing lockdown-not-lockdown by listening to Bourbonese Qualk mp3s

Henry is looking across the Yellow Sea at China.

Caiwei is happy that she made friends with Pig, the black cat in her neighborhood bookstore.

Yan would like to summarize the inaugural issue of Chaoyang Review with three WeChat stickers: