S01 Episode 6: Being Cute in WeChat’s "Moodboard Industrial Complex"

McDonald’s spam emails + GIF Talent Agencies + Cat Ideology Reveal + Celery Fanclubs

In the house this week: ZhiShu, Maomao, Yan, Krish, Tianyu, Simon, Jaime, Christina, Caiwei, Aaron, Henry, ████, and Yi-Ling.

Krish: Yan and I are obsessed with WeChat stickers.

All of China is. 40 billion messages are sent on WeChat everyday, and if our conversations are any indication, at least 10 billion of them are stickers.

They’re the vanguard of expressive language online. A moodboard of the country. They’re how memes replicate, how slang terms seep into daily use. How the *felt* is *said*. I sometimes think in stickers. Mostly this one:

As a whole, they’re big business. WeChat stickers are a Moodboard Industrial Complex—complete with leaderboards, speculation markets, sticker talent agencies, copyright trolls and a strict censorship mechanism.

In my personal hierarchy of digital communication forms, stickers occupy hallowed ground.

They are above emojis and slightly below ‘silence’ in expressive range. WeChat, in particular, allows for freewheeling sticker-laden conversations, to the point where it’s useful to think of “stickers” as its own category of expression. A genre.

Try explaining this in another medium:

Krish: WeChat stickers are woefully understudied. I think of them as representing what queer theorists call “anesthetic feelings”—an expression that protects against the overintensity of feeling. “A predisposed disappointment to avoid the crushing feeling of actual disappointment,” as Lauren Berlant puts it.

When so much of life is mediated through WeChat, stickers become a necessary mask. A way to be visible without committing. Communication without actually communicating. There should be academic departments studying this (hire me).

Tianyu: WeChat stickers must have been what Marshall McLuhan meant when he wrote, in 1964, that “the medium is the message.” It would be impossible to reimagine conversations in Chinese contemporary life without the conditioning by—and of—these aesthetics, symbols, and representations. Much literature has been written about the use of stickers and memes by China’s nationalists while battling Taiwanese and Hong Kong activists on social media, showing that these collectible visual forms are an integral part of our online political language.

Yi-Ling: My first exposure to the art of the digital sticker was not on WeChat but on Line, in Taiwan, but also used in Japan and Korea. I was struck by its irony and dark humor. Line stickers often tapped into the concept of “kimo-kawaii” (in Japanese: cute and gross) which in some ways feels like a close cousin to the Chinese idea of “sang.” There were entire collections featuring “Moon”—a staple character who has an entire narrative: looking for a new job, watching his bank balance dwindle to zero, watching softcore porn, making friends with a cockroach.

Simon: I’ve joked to friends that the one advantage of working an office job in China, vs. the freelance life, is the amount of stickers you can collect from a variety of cursed groups. However, the darkness of work-life specific sticker packs can often be pretty shocking. It’s totally normalized to receive a sticker from a colleague that, on surface level, would seem to imply they want to physically harm you or that they’re contemplating suicide. On the one hand this speaks to the lack of agency within (white collar in this case) Chinese work life—the only way to express displeasure is by making a joke about violence—as well as the strange, self-contained atmospheres of many offices, where what might be considered extreme behavior outside becomes part of daily life.

Christina: The closest analogue to East Asian sticker culture in the U.S. is reaction GIFs, first popularized on Tumblr but still thriving (despite Gen Z mockery) on Twitter and in messaging apps everywhere. Both are ways of expressing hyperspecific emotions in concentrated and collectible forms, but reaction GIFs tend to rely so much more heavily on footage of real, expressive humans, while digital stickers make better use of illustrated characters. These illustrated stickers create a safe space for people to access (and normalize!) emotions that are probably too unseemly for pop media—depression, slovenliness, anger, and even sometimes sluttiness.

████: So, we should clarify that WeChat allows for two kinds of sticker use—“packs,” which are created by illustrators / companies and uploaded for review and platformed by WeChat and “custom”, which is any GIF you have.

I think Christina’s point is especially true for custom stickers, which in my experience tend to be more extreme and specific than those in the illustrated “packs”, and don’t go through any centralized review & distribution process. In addition to functioning as “anesthetic feelings,” stickers can also simultaneously work in the opposite direction as a kind of “super-aesthetic” communication that allows people to say things earnestly that they might not be as comfortable writing out directly (most obviously for the emotions Christina mentioned, which I am not ashamed to say represent the majority of my custom sticker collection). But especially combined with toxic workplace cultures like Simon mentioned, that can be...bad.

Henry: Unlike in some economies, custom stickers can only be hoarded for so long; you’ve got to show off your wealth by sending them at the opportune moment, at which point—after people laugh or express their appreciation—anyone in the group chat can save them.

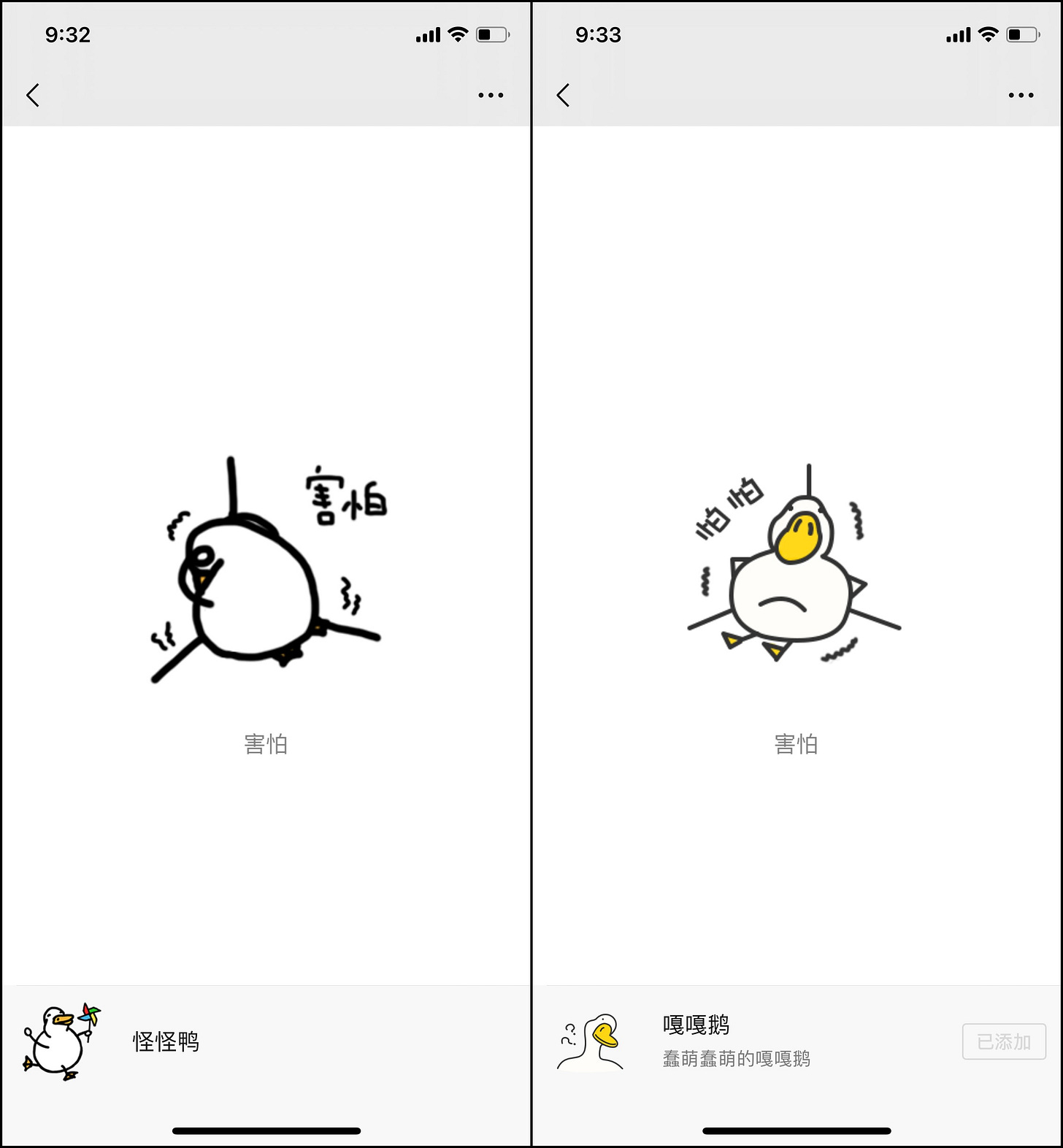

But sometimes, a sticker pack is suddenly taken down, effectively becoming a limited edition collectors item for those of us lucky enough to have copped it. One of my packs, 怪怪鸭 (Weirdo Duck, below left; note the button for “download” is missing), disappeared in such a fashion—I suspect because of copyright infringement (see below right for original but inferior version), but we’ll never know. Now, the only way folks can use Weirdo Duck is by saving each as a custom GIF—or I suppose buy my iPhone (plz DM me if interested). Unlike, say, Air Jordans, purposefully manufactured in limited batches, these beauties testify to the twists and vagaries of history, like the priceless Micky Mantle baseball card, 500 cases of which were thrown off of a tugboat in 1952, because their owner considered them trash.

Krish: This week’s Chaoyang Trap interviews two of our favourite WeChat sticker creators—one who started making stickers a year ago, and one who started 5 years ago.

We wanted to unpack how China’s predominant online art form is created and consumed, what the inner life of sticker makers looks like, and how they perform an important kind of witnessing. Both creators are women, who draw on their often depressing experiences at the workplace.

As an artistic medium, WeChat stickers are undergoing a process of ruthless standardization. When introduced in 2015, stickers were an experimental feature. That meant more weirdness in what was being produced, and less scrutiny over what was being platformed. Today, sticker makers are squeezed for margins, reliant on an opaque censorship mechanism and a black-box algorithm for visibility.

Unless you’re signed to a larger brand or an assembly-line “sticker studio”, there is only one path to economic security for China’s many brilliant, niche, observant, genius independent sticker makers.

That path has become a template.

Step 1: Create a single, ownable, copyrightable character.

Step 2: Create endless variations of this character and post constantly to see what sticks.

Step 3: Create product lines across platforms—Taobao, TikTok, Weibo, WeChat.

Step 4: Pursue rapid commercialization at the first sign of success.

Step 5: ???

The template is a trap, forcing labours of love to change to...just labours. Where comic artists (like Wangxx of ‘Seal & Friends’) can dabble in stickers as an experiment, there are few alternatives for sticker illustrators for whom messenger stickers is their sole medium—no alternative publishing outlets, no interested non-profit galleries or art institutions, no creative channel for work that isn’t purely ‘consumable.’

Caiwei: I once interviewed 12Dong (十二栋), a studio that runs multiple popular WeChat Sticker IPs including Budding Pop (长草颜团子). Starting from stickers and comics, they’ve built an insane business pipeline. They now run the biggest claw machine store chain in China (including the J-Stop 夹机占 in Sanlitun).

12Dong, and toy companies like Pop Mart, are both considered to be part of China’s Chaowan (潮玩) industry—a fascinating, almost untranslatable term. “KAWS meets streetwear meets videogame loot boxes” is one possible description—these companies deal in sticker-like parades of physical toys in repeating motifs and slight character variations, sold in “blind boxes” optimized like slot machines. It’s gigantic, even cultivating a secondary market of opened blind boxes on Taobao—much like the yoghurt speculators Yan wrote about in the last issue. We’re not far from a Wechat Sticker Con.

Krish: Stray even slightly from that route and it’s a state of permanent precarity, as both our interviewees explain.

Fuyan-kuma (敷衍熊) and YimaoRen (一猫人) have cult followings and what, on the surface, look like successful trajectories for indie artists. YimaoRen was approached by Mcdonald’s for a brand collaboration when they had barely 300 Weibo followers. Fuyan-kuma has close to 100,000 and is targeting a million TikTok followers in 2021.

And yet, the stickers at the heart of their practice are barely sustainable, forcing them in heartbreaking ways to distance themselves from the life that gives their art power and resonance.

Both YimaoRen (cute, emotional, heartfelt, imaginative) and Fuyan-kuma (indulgent, cheeky, subversive, edgy) have been used by millions.

Neither has ever been interviewed.

We try to address this sad and ironic negligence below. Why has no one gotten into the minds of the creators who have helped facilitate millions of unspeakable conversations?

In a society marked by an inability to self-diagnose, can we think of stickers as a shared cipher - the first draft of a vocabulary?

Lurk. Shitpost. Hustle. Repeat.

By Krish Raghav

(All images used with creator’s permission)

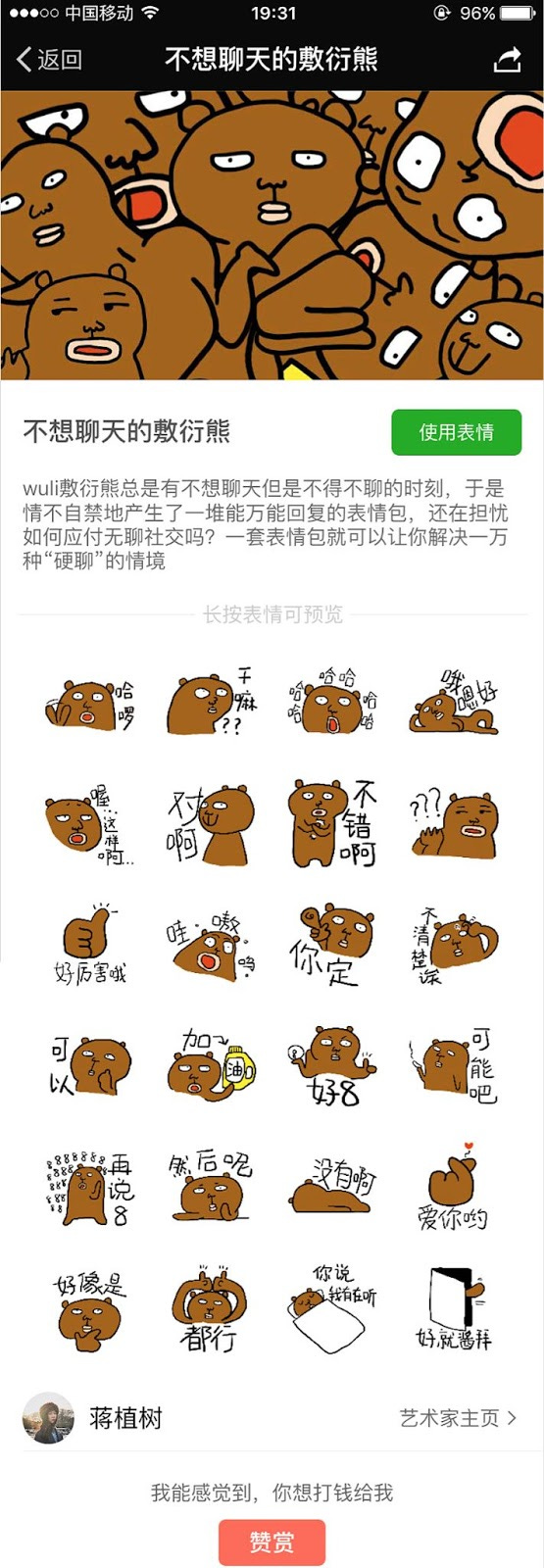

Krish: Fuyan-kuma (敷衍熊, lit. “half-hearted bear”) is my favourite WeChat sticker series. It’s classic “Weird WeChat”—a bit dark, a bit violent, a bit too gleeful in its dark violence. It’s inspired by the “gross cuteness”of kimo-kawaii, a semi-autobiographical diary of ennui and tiredness starring the titular half-hearted bear. I like using it at work to quietly signal my alienation and lack of enthusiasm.

A Fuyan-kuma sticker pack, to me, is somewhere between experimental narrative comic, flash poetry, mood board, and meme. Over time, as Fuyan-kuma’s skin tone has lightened (for “commercial reasons,” according to the creator), the series has also reflected the shifting mood among middle-class young urban professionals (the sticker’s primary demographic) from playful rebellion to weary resignation.

I chatted with creator Jiang ZhiShu (蒋植树) on WeChat. She talks about Fuyan-kuma’s origins, inspirations and future. This interview is translated from Chinese and edited for clarity.

Krish: Hi! Could you introduce yourself?

Jiang ZhiShu (she/her): Well, I’m the creator of Fuyan-kuma (敷衍熊). This is my creator alt: 蒋植树 (“JiangPlantsTrees”). I chose this because my birthday is on Arbor Day. I’ve been drawing Fuyan-kuma for five years now—it started as a WeChat sticker pack in July 2016. I quit my job in September last year to work on illustrating full-time. Now I mainly rely on my Taobao store for a living. It's so miserable. I don't know what else to say lol.

Krish: How did that first sticker pack happen? What was the “sticker scene” like at the time?

Jiang ZhiShu: I’d just finished grad school, and WeChat’s Sticker Gallery was open to user submissions. I literally just drew a set within an hour and uploaded it.

I guess I found all the existing stickers at the time too cloyingly sweet and too nauseatingly cute. I prefer something more “low”—a kind of slapdash ugliness. I also hate chatting online, so I wanted to create a sticker pack that reflected my hatred.

On WeChat, I think the popular sticker set at the time was Tuzki (兔斯基), and since I was studying in Hong Kong, I was familiar with a lot of the weird and wonderful Line stickers.

Krish: Is there a Fuyan-kuma “cinematic universe” that you keep track of? Are you consciously building a “world” or a narrative through these stickers?

Jiang ZhiShu: There’s no structure to the world...he’s just a slob otaku bear (肥宅的一个小熊) who dislikes social pressures and lives a slob otaku life. He’s surrounded by archetype friends that we can all recognize—simps, dweebs, “green tea bitches” (绿茶婊), and queers.

Krish: What is the process of getting a sticker pack on the WeChat platform? Have you ever had to change a sticker, re-do a drawing, or take a sticker pack down?

Jiang ZhiShu: They have a separate platform for sticker creators. They used to be really slow to audit and approve, but I never really encountered any big problems. Not sure if they staffed up or streamlined the process, but it’s really fast now. You can get a pack uploaded in 2-3 days.

You can get certain phrases or internet slang flagged and rejected, then you have to write an email to explain to them what the expression means, or find similar examples that have already been approved on WeChat. I faced that with a “草“ (cao, lit. “grass”) sticker in my third pack. It um...caused some concerns...but I (successfully) explained that it means “lol” in Japanese slang, and not...you know. (Note: “Cao” is an all-purpose homophone for “fuck”.)

Krish: What’s the most popular Fuyan-kuma sticker?

Jiang ZhiShu: The first pack is still the most popular, because that one is a bit more demented, more unique.

Krish: I feel like your next milestone was in 2017, when you released the “Fuyan-kuma’s Late-Stage Terminal Laziness” (敷衍熊懒癌晚期) pack. This one is my favourite, and it really captured this rising mood of “sang” 丧 culture and laziness-as-resistance in China. Could you talk about the inspiration behind this pack? What were you reading or watching at the time?

Jiang ZhiShu: I was still working then, and yeah, we were deep into sang culture. We were all trying to find the space to focus on ourselves, and seeing an emptiness within. I wanted to try and capture a “Fuyan-kuma” approach to workplace life, to maybe show that young people today can legitimately choose to “reject” what they felt was unimportant.

The dark side of workplace culture was definitely an influence. In their jobs, people are often deploying academic-paper levels of rigor to frivolous problems like “increasing engagement on a Kuaishou channel.” It’s darkly funny, but then they’re also suffering the constant PUA of toxic workplace leadership. I think this “rejection” comes from that combination —this mismatch of intelligence and education with the reality of what many jobs require.

Simon: Interestingly, "PUA" has picked up a somewhat different meaning in Chinese "office" English—not literally referring to "Pick Up Artists" all the time, but to emotional exploitation, quasi-brainwashing, and gaslighting in the work environment more generally. Of course, the way the term has travelled and evolved reflects the same virality though which stickers are transmitted. Also, I have colleagues who pronounce it "pua" :)

Krish: A few months ago, you put out a sequel of sorts: the “Fuyan-kuma at Work” (敷衍熊打工篇) sticker pack. This one has a lightness to it that feels like you’re reflecting back on your old workplace life rather than actively suffering through it.

Jiang ZhiShu: I think the post-95 and post-00s generation are much more reluctant to work overtime or to indulge in work-circle socializing. They dare to refuse these things. So where “Terminal Laziness” seems to say you *can* resist—that you don’t need to be enthusiastic at work all the time, that anger is justified, that you can foster a little resistance in your heart—much of that is normalized in work culture now (think “996”), which is reflected in the “At Work” pack.

When I drew these, I was watching a Japanese drama called "I Will Not Work Overtime, Period“ and reading this Taiwanese comic diary called “Can I Not Go To Work?” (可不可以不要上班).

I think, since it's becoming an aging and low birth-rate society earlier than us, Japan has a maturity and courage in addressing youth ennui that feels “ahead of its time” in China. For various reasons (SARFT, “societal norms”), China hasn’t quite excavated and completely unpacked the minds of its own young.

You can find a lot out there that’s “positive energy”, but those of us who’ve been repressed/depressed for a long time are relatively under-represented. It’s probably why all these insane (and dark) Bilibili videos go viral often—it’s a form of cathartic venting for feelings running underneath.

Krish: Do you see yourself as part of a community of sticker artists? Do you communicate with them, or exchange experiences and tips?

Jiang ZhiShu: I do, but I also have a social phobia. It’s very difficult for me to take the initiative, so I usually just wait for others to contact me. There are groups, but I’m more of a lurker, really. I’ll send a few stickers, shitpost in my mind, and go back to drawing by myself.

Krish: Do you have any artistic ideals or creative goals you want to achieve as an illustrator? Do you see this as a “career”?

Jiang ZhiShu: I’m neither professionally trained nor very good at “illustrating,” so I prefer to just be called a “sticker maker.” I guess my goal is to create an “IP” (intellectual property) that is popular, and to that end I’m extending the Fuyan-kuma world outwards beyond stickers—to TikTok short videos, Taobao merch, etc.

It’s a career, of sorts. I’d love to keep drawing, and maybe put out a book, given the chance. Books aren’t very profitable now, but it’s a dream for every creator to be able to publish at least one. I’m going to sign with a company that manages sticker artists, so that’s a step up.

Krish: Can you talk about “the sticker economy,” such as it is? What are the routes to economic security for a sticker maker?

Jiang ZhiShu: It's very difficult to make a living with stickers alone. You have to create a consistent IP, ideally one you own yourself, which then exists across platforms and forms—Taobao, Weibo, TikTok, WeChat, Xiaohongshu. It’s a precarious market because the competition for IP is intense. There’s a lot out there, and only the IPs that can continuously produce high-quality works or constantly go viral can succeed. So creators need to have one foot in the “fan economy” to go viral, and another in rapid prototyping to drive...well, consumerism around new products.

Krish: Why do you think the environment for creation and commercialization is so hostile to creators?

Jiang ZhiShu: Hot online products are more often not driven by well-known IP. They can be viral phenomenon, such as the “Kitten that Carries Everything” (万物皆可举的小猫), or the TikTok-famous “Ugly Fish Mask” (绿头鱼头套) These aren’t well-known IP with big capital infusions like Line Friends, but are a kind of “SEO” manipulation that rely on catchphrases, memes, or mentions by influencers. Cabbage Dog (菜狗) is a good example—an older illustration that became a hot-selling product due to buzzwords in the news. Capturing fickle attention isn’t easy, and when you’re focused on going viral, you can’t really go deep.

So there’s an adjustment I have to make with Fuyan-kuma—from a semi-autobiographical, narrative character to a visually-appealing platform for “products” that can sell well.

Krish: You have close to 100,000 Weibo followers, as well as fan groups on Weibo and WeChat. How do you run your fan community? Do your fans influence your work?

Jiang ZhiShu: My fans actually built the groups themselves, because I didn't have the energy to manage it at that time. They call themselves “celery.”

Krish: ...celery.

Jiang ZhiShu: Yeah. Since I’m called “Zhi Shu”, the same name as a character in a Taiwanese drama (based on a Japanese show) called “It All Started With a Kiss,” (惡作劇之吻) they named themselves after Xiang Qin (湘琴), the female lead who has a crush on Zhi Shu in the show. But they swapped the “qin” character with the word for “celery” (芹).

I’m really thankful to them. They help me manage the fan ranks and keep order. They also inspire me a lot, pointing me to trending topics or widespread pet peeves. I learn a lot from them.

I guess “resonance” is one of the most important qualities for a WeChat sticker maker. Only sympathetic, truthfully observed work can win everyone's recognition and approval, so having an attentive fan group like this is such a blessing. I send works-in-progress to the group sometimes, to get feedback, to learn what they like and dislike.

Krish: And finally, what other WeChat stickers do you use these days?

Jiang ZhiShu: I’m still drawn to the niche, “ugly” ones. I save a lot of meme-related stickers, which aren’t very easy to use in ordinary chats. I like Teacher Guo (郭老师), Brother Yaoshui (药水哥), and the classic “Panda Head” biaoqing.

Krish: Do you have a personal favourite Fuyan-kuma illustration?

Jiang ZhiShu:

Simon: Talking about “sang” culture makes me think about something I’ve wondered about recently. It may be a very “my own generation is the best/worst” perspective, but if discourses about China often talk about the speed of growth and an atmosphere of entrepreneurship, isn’t there an inverse to that growth? The faster things come together, the sooner people might want to opt out. Starting to twitch involuntarily as I recall the countless poorly-considered references to accelerationism and misappropriations of Mark Fisher’s writing that I’ve had to translate, but should we ask if an accelerated rise also results in accelerated entropy? To put it another way, it took Europe and America around a century to get from capitalist industrial takeoff to SoundCloud rappers, and China only 40 years.

Krish: ...that actually brings us perfectly to the second interview in this episode:

Is YimaoRen Okay? Is Anyone Okay?

Yan: It’s very hard to describe why I like 一猫人 (YimaoRen, lit. “cat person”) so much—there’s this strange tendency in WeChat behaviour to champion an underdog (undercat?) sticker pack and make it “your own.” I’ve followed YimaoRen (on Weibo as well as WeChat) from very early on, and being witness to their growth and evolution feels a bit like being an aunt or a distant relative.

Krish: YimaoRen is cute in this precious way that feels so rare. There’s a purity to the expressions, a non-ironic wide-eyed wonder made somehow more adorable by the *just-slightly-too-slow* animation speed. It’s interesting, looking back at my sticker use, that I reserve certain characters for “true” ZQSG feelings rather than ironic reactions. YimaoRen was one of them.

Yan: I chatted with co-creator Maomao (猫猫) about the sticker’s pandemic origins, chaotic process, and McDonald’s collabs. This interview is translated from Chinese and edited for clarity.

Yan: Hi! Could you introduce yourself?

Maomao (she/her): I’m the “main” creator of the 一猫人 character and sticker packs. I draw and come up with the concepts, and I collaborate with a former classmate—now a graphic designer—for the animations. He used to be called 大熊猫 (“Panda”), and I was 猫猫 (“MaoMao”), so our combined creator alt is 大熊猫本猫 (“PanDaCat”)

Yan: YimaoRen just celebrated its one-year anniversary! How did it all start?

Maomao: It came out of the pandemic at the beginning of last year. I moved back home to live with my parents in Shenzhen. There was a certain amount of pressure and anxiety, so I began to draw and paint by myself. I was not a trained illustrator, nor did I have any foundations in painting. I taught myself through Bilibili videos.

Back in college, I discovered I had a bit of talent for captioning funny pictures, and my meme “creations” were popular with classmates. I also helped a few friends come up with concepts for their WeChat stickers packs. Some of them were very well received.

Panda had gone back home too, during the pandemic. He was drawing stickers as well, and we’d riff on ideas. I’d just randomly drawn the YimaoRen character one day, and I sent it to Panda to take a look. There was this moment of mutual recognition—DENG! A lightbulb moment that this character could work as a protagonist.

Yan: Can we talk about McDonald’s? In 2020, McDonald’s publicized an official collab sticker pack with YimaoRen. How did that happen?

Maomao: When things went down, YimaoRen had been going for around half a year. It didn’t seem like it was catching on that much, or doing great numbers. We’d just discussed changes and additions when the email dropped.

We were shook.

McDonald’s China was inviting us to cooperate with them directly. They’d seen our sticker pack, found it cute, and wanted to talk about an official collaboration. To be honest, I thought it was a scam at first. I mean, we had less than 300 Weibo followers. We were tiny, extremely niche. Even if they’d found us “cute,” it didn’t sound right. You’re McDonald's. I was also scrutinizing the email, like, shouldn’t McDonald's China be called Golden Arch Pvt Ltd?

(Note: McDonald’s China did officially change their name in 2017 to “Golden Arch” 金拱门—a move netizens mocked as unimaginatively literal, leading to memes like this:

Long story short: it was not a scam.

McDonald's was a critical and important turning point in the YimaoRen story. We were close to calling it quits before it happened, thinking about finding new jobs, changing course.

They’d initially asked us for 3-5 stickers, and requested a timeline and quote. It was our first business deal of any kind, so we started by searching online for quotation templates. We weren’t that confident, so we quoted a very low price. The advice was, if you have McDonald's on your client list, that's enough. The endorsement mattered. If you lost money, so be it.

They agreed immediately to our offer. They didn't even read the details, just said OK, and let us ideate. Our advertising background served us well. We made a hilarious proposal document, and a lot of it was accepted.

There are pros and cons to this kind of brand collaboration. It doesn’t appear on our artist page, for instance. Many noticed McDonald's but didn't know who YimaoRen is, so it didn’t help us much in growing the fanbase. The real advantage is potential—when we talk to fat cats and top dogs in the future, we have a big golden arch on our resume. Most of all, it gave us hope that there was commercial value in what we were doing.

Yan: So what’s your process like? How do you come up with ideas for stickers?

Maomao: It’s a chaotic process. It’s like surfing the web and connecting A to B to C and suddenly everything makes sense. I take long baths. I’m the kind of person who, if I have five dreams in one night, will remember every single one. I write down ideas constantly.

Yan: That's amazing. Do your dreams ever become stickers?

Maomao: Maybe? My list is really long, and sometimes I never get to the good ideas. There are some truly strange things in my ideas document. I can read some out for you:

“画画不积极,催更不积极” (“Slow to draw, slower to follow up”)—what kind of sticker can this be?

I even wrote: “人间枯萎子,少女心注入” (“A dose of shoujo vibes, to bring the withered back to life”). Like, WTF?

Also “青山不改,绿水长流” (“The mountains remain evergreen, and the waters everflowing”)…for some reason.

Let’s see, what else...oh I like this one: “梦境是言灵的具象化” (“Dreams are the first draft of reality”). I wrote this a while ago but haven’t figured out how to represent it yet.

Yan: Do you think about “world-building” at all—is there a YimaoRen universe that you have plug ideas into?

Maomao: The world-building came much later. We established early that YimaoRen was a cartoonist, but we didn’t think about his personality or hobbies. All of that develops slowly as we create more scenarios and situations for YimaoRen.

Drawing the stickers is such an emotional investment, and you put so much of yourself into it that one day, I suddenly had this intense feeling that I had a son. That YimaoRen was like my child, one I’d imbued with dreams and hopes and yes, even my flaws. His world, in a way, is a reflection of my own—he does, on my behalf, what I want to do, what I can't, what I dare not. So we made this feeling a part of the world. On Mother’s Day, we “revealed” that our PanDaCat alt was, in fact, YimaoRen’s mom.

Yan: So YimaoRen is a...person? Not a cat.

Maomao: How can I explain this to you? Do you know Hello Kitty?

Hello Kitty is a little girl, you know?

Yan: Isn't Hello Kitty a cat?

Maomao: Hello Kitty is a little girl. A third grader from England.

Yan: My worldview is collapsing before my eyes.

Yan: So how does a sticker pack come together from these disparate ideas? Maybe we can use the latest one as an example?

Maomao: This latest one was sparked by one sticker, which was a still image when I first painted it. I was really moved by it for some reason, it really sparked something. Panda didn’t get it. He just thought no one would use it.

I was fine with that, and when he asked what the theme of the pack would be, I said “天马行空”— “letting creativity run wild.” I had a lot of unused material that was discarded for being too “out there” and I brought it all together and packaged it for this one. It’s really special.

Yan: How’s the traffic data for this pack?

Maomao: It's very bleak.

Yan: How do you feel about that?

Maomao: I’ve made my peace with it. Making it made me happy, and this was the result I expected. I’m in it for the long-term, so I will continue to experience, observe, accumulate, mull and produce new content. I think sometimes you do feel powerless in the process, but it’s stimulating and the work keeps me going. It took me back to the pure joy of just wanting to paint well, and when YimaoRen can push me to expand my horizons, things like revenue or data become less important.

Yan: Can you be financially secure as a sticker maker?

Maomao: Impossible.

Almost all our revenue from the McDonald's collab was invested in copyright protection and trademark registration, and the cost is actually very huge. It’s a really sad situation for small creators in China. Everyone urges you to immediately secure copyrights as soon as your work gets even a little bit of exposure. The cost is prohibitive, but friends persisted: “Borrow money from your parents if you have to. If you’re successful and don’t do this early, you might find someone has claimed ownership first.

I was speechless. Many creators are really being cheated like this, by fraudulent copyright claims on their behalf. As a result, the original author “infringes” the rights of the pirates when they continue to use it, and the pirates can turn around and seize all your work. We’re still in the process of registering all our copyrights, but it’s a long journey.

Then there’s payment terms. There are so many examples online of creators drawing half or even 100% of a project before it’s called off, and you don’t get any money. You don't even have social security paid for you, and then you destroy yourself working for hundreds of hours.

On top of all that, income from WeChat stickers and red envelopes (Note: kind of like tip jars), for us, is quite low.

Yan: Do you think it's because people aren’t used to paying for this content?

Maomao: How do I say this? The vast majority of WeChat sticker users who are willing to pay are in China's second, third and fourth tier cities. Their aesthetic tends very differently—either big written characters, memes from TikTok, or “clip art-style” imagery. Our kind of work doesn't cater to that aesthetic. I’d rather not make money and continue to create the art I believe in.

Yan: It feels like the only way to survive as a sticker maker is to...well...commercialize an “IP” across platforms. Create products.

Maomao: You’re right. You can't support yourself only with stickers. We calculated it—you take the number of downloads and divide the number of paying “fans” and tips, and it’s shockingly low. And that’s just the number—most “tips” are less than 5 yuan.

For instance, the first sticker pack has been downloaded nearly 1 million times. It looks like a lot, but the return is very little. YimaoRen stickers have been sent in chats over 50 million times.

Yan: Do you have any plans for YimaoRen in the long run? You mentioned going back to finding a full-time job?

Maomao: I'm looking for one now, but haven’t found one yet. I’m looking for something a bit more leisurely than before. I used to be a professional minion. All my previous jobs were “007.”

Yan: So unsuited for a side-hobby.

Maomao: Yeah, and you really damage yourself and your mind. And recovering at home isn’t ideal, since there’s a different kind of pressure from your parents. When I’m job-searching, I think I might set a goal of “no 996, no 007,” and settle for a lower, but stable salary. My parents are really hard on me. They think I’m a squatter at home.

Yan: Tell me about your fan community on Weibo and WeChat.

Maomao: My fans on Weibo mostly comment or DM me to push me to release new sticker packs. I have a WeChat group of over 100 people. We’re like friends, talking about random things. Unlike on Weibo, my WeChat fans care about my well-being. They constantly check in on me—if I’ve had dinner on time, if I’ve stayed up too late. They even know that I really like to drink Iced Lemon Tea, and they drop links whenever there’s a sale.

My fans really like my daily updates outside the sticker packs, whether it’s an illustration, comic strip or short video. I told them it’s because both me and Panda are unemployed. What else can we do? When we’re not sleeping, we draw. That’s why we manage to update daily.

If I do get a full-time job, I can only prioritize creating new sticker packs. So I told my fans to cherish this time. When both of us are jobless.

Aaron: It's interesting if unsurprising that both Jiang ZhiShu and Maomao mention Japanese culture or Hello Kitty, since it seems like a lot of WeChat sticker IP has learned lessons from Japanese mascot design, and the way those mascots fill a need for anesthetic expression. Gudetama, a “sad egg yolk crippled by existential despair”, is an especially good example of this, like in this interview with Matt Alt or the head designer. The whole thing feels to me like something that's rapidly moving from "wacky Asian phenomenon" to "standard method of communication" in Western eyes.

Jaime: I want to suggest we can even trace a lineage of sticker communication further back to the iconography and visual communication systems in Chinese decorative art and print history. Certain self-contained narrative universes and protagonists of sticker packs lend themselves as essentially deconstructed versions of woodblock new year’s picture (年画, nianhua)—literal sticker-posters that people used to put up on their walls and doors for vibes.

These locally mass-circulated woodblock prints, under various schools and aesthetic subgenres, can be epic group portraits that are essentially “positive energy” mood boards, FILLED with internal drama, featuring sets of symbolic characters and illustrating relatable content drawing from scenes of daily life, traditions, current events (i.e. village gossip), to nature worship and spiritual aspirations—not so unlike the ethos in today’s sticker packs. Another interesting parallel is as folk art, new year picture makers were also often anonymous and considered lower-rung than their “fine arts” counterparts.

Character-, reaction-, and coping mechanism-driven sticker packs like YimaoRen and Fuyan-kuma also make me think of the iconography of kungfu manuals in wuxia traditions—if we consider the context and narrative of each pose in a series of moves being contained within one icon of illustration, captioned by a poetic or meme-able title. And speaking of poetic agency in mass communication, let’s not forget graphic design was Lu Xun's passion.

Tianyu: That’s it for episode 6! If you enjoyed this, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription, or forward it to a friend by hitting the shiny button below! All of our revenue will go towards paying contributors on time and supporting writers. We also welcome feedback, story ideas, and cute animal GIFs via email (hello [at] chaoya.ng) or Twitter (@ChaoyangTrap).

Krish: Next time: Chinese towns on Wikipedia, Chinese seniors on RED.

Outro music this week is the lovely new single from enigmatic Beijing duo TOW, composed of Yang Fan (Hang on the Box/Ourself Beside Me) and Liu Ge (The Molds). This one reminds me of evenings spent between the basement murk of Fruityspace and the too-bright 7-11 nearby.

Tianyu: Bye!

Krish Raghav is a comic-book artist in Beijing who has one-too-many 我很好 stickers.

Yan Cong is a Beijing-based photographer, and one of the founders of Far & Near, a Substack about visual storytelling in China. You should subscribe!

Tianyu Fang is a writer who grew up in Beijing and is an avid collector of now-banned Jiang Zemin stickers.

Maomao is a sticker maker based in Shenzhen. 一猫人 is on Twitter. Please follow 一猫人.

Jiang ZhiShu is a sticker maker based in Beijing (but not Chaoyang). You can buy Fuyan-kuma merch on her Taobao shop.

Jaime (bot) is a critic and translator in Beijing who works in Chaoyang and is moving to Chaoyang. She is also a contributing editor at Spike.

Yi-Ling Liu is a writer in Beijing. She likes to wall-dance—both online and at the climbing gym.

Henry Zhang is a writer who is accepting offers for his phone full of priceless discontinued stickers.

Christina Xu used to write about Chinese internet culture, but now mostly yells about and on the American internet.

Simon Frank is a writer, editor, and musician/slob otaku human based in Beijing.

████ is a ███████ and ██████████ at ███████ in ███ , and often wishes he could send stickers face-to-face.

Caiwei Chen is a writer, journalist and podcaster. She has a big collection of “begging for mercy” stickers when editors are at her throat.

Aaron Fox-Lerner is a writer, editor and game designer based in Beijing. He has his own sticker:

Thanks for sharing.

https://nivapackersandmovers.com/

Have you guys had dinner yet?