Open Sesame x Chaoyang Trap: Taobao Ethics / Cursed eCommerce / Crab Justice

A special preview of Open Sesame Issue 3! Deals on spycams + Export-quality curses + Llama monopolies

Sasha: Hey!

Aaron: Yo.

Tianyu: Hi!

Jaime: Hello.

Krish: Hello!

Krish: This is a…slightly different episode of Chaoyang Trap. This week we’re presenting a special preview of Issue 3 of Open Sesame Magazine, which is out now in mainland China! It’s long been a fave, helmed by two Chaoyang Trap members Sasha and Aaron!

Tianyu: Made by the graphic design studio Lava Beijing, Open Sesame is an irregular print magazine devoted to the weird and wonderful world of Taobao, *the* Chinese online shopping site. The theme of this third issue is “Taking Responsibility,” examining the ethics, blurred or otherwise, of internet shopping and the choices we make when confronting this behemoth of a platform.

Sasha: I’m obsessed with Taobao. I made a magazine about it basically because I spend too much time on the app and wanted to make all those hours worth something. From the day I moved to Beijing from Russia in 2014, I kept hearing these stories of what you could get on Taobao: a positive pregnancy test, a visa, anything from a paperclip to a tractor. I started using it, at first, for daily needs.

I’m not quite sure how, but after that I got addicted to it. I guess because they’ve set it up so well and have such an effective algorithm. There’s a lot of weird stuff on there, and once you click on one weird thing the algorithm starts recommending hundreds to you. Way before I started the magazine, my friends already had an active WeChat group for sharing weird Taobao findings. This was also around the time that Instagram got blocked in China, and Taobao filled the same need for endless scrolling. No matter where you are in the app, it recommends more products to you: at the bottom of a product page, in your shopping cart, when you check your account history—really anywhere.

Aaron: More than just a shopping app, Taobao really feels like it’s been set up perfectly as a form of entertainment, far more so than competitor JD or American sites like Amazon. I think its parent company Alibaba does a lot to reinforce this, from billionaire Jack Ma’s high public profile (at least until he came under recent government scrutiny) to the Double 11 shopping festival galas that the company puts on each year. The app itself consists of a lot more than just products and sales offers, with an Instagram or Xiaohongshu-like browsing section and an entire livestreaming tab full of hawkers, ranging from gender-bending online celebrities pitching lipstick to farmers in remote provinces slicing vegetables with high-pressure hoses.

When it comes to Taobao’s market for magic spells and occult objects, for example, the products really seemed to range from the sincere to those purely there for the aesthetics or shock value.

The entertainment value of the app has led to its own strange form of vendor clickbait, where people advertise pretty normal products with the most disgusting or bizarre image they can get away with.

Under the constant entertainment and seamless experience, there’s clearly a lot of barely seen labor: vendors striving to stand out, delivery people racing to deliver absurd amounts of packages, programmers working on 996 schedules to keep you on the app for just another minute longer.

Krish: Here are three stories from the sumptuous print edition of Open Sesame below, adapted for group chat goodness. If you’re in China, you can buy Issue 3 in print (highly recommended) from Weidian here.

Taking Responsibility on Taobao

By Open Sesame Editors

When we open up Taobao or any other shopping app, we’re often looking for a lot more than a specific thing to buy. We don’t just want to make a purchase, we want to shop, to explore, to gawk, to engage in the Chinese consumerist version of the endless scroll, a brief escape from our daily lives. And yet there’s a dense web of responsibilities underlying this escapism. An intricate logistics system, powered by overtime-addled tech workers and underpaid delivery people, enables us to see something on one side of the country and receive it two days later.

Countless vendors’ livelihoods depend on attracting our attention, while we worry about the waste we create and what our purchases say about our values.

Given all that, when we decided to theme our third issue around responsibility, we were expecting to take a sober, serious turn. Instead, we’ve ended up with something surprisingly playful, exploring the absurdities and ironies that naturally occur when lofty ideals and urgent needs collide in the online marketplace. Sometimes taking responsibility can turn out to be the best form of escape after all.

Quiz: Forbidden on Taobao

By Joy Chen and Josh Gibbs

🅠 Which of these items can you actually (still) buy on Taobao?

🅐

BADGE OF THE COURT: YES

Selling suits and accessories of government offices was banned on Nov 21, 2014, but badges and suits of the court are currently available.

SALT: YES

In 2013, salt was banned on Taobao based on Regulations of Salt Industry, because the salt industry used to be state-owned. But now it’s available widely.

ANIMAL CROSSING: ❌NO

On Apr 10, 2020, Animal Crossing was banned on Taobao and other shopping sites because of some “regulations” and certain political user-generated content.

RESIDENCE PERMIT AGENCY: ❌NO

In the Taobao regulations, services to apply for Residence Permits and other social or administrative services are classified as general violations.

LIVE FIREFLIES: ❌NO

On May 24, 2017, Taobao banned live fireflies because they were unclear about the breeding industry, and thus were not qualified to review the products.

SIM CARDS: ❌NO

From Sep 6, 2016, people cannot purchase Chinese telephone SIM cards on Taobao, due to requirements to register real names for every telephone user.

SINGAPORE TOURIST VISAS: YES

Yes, it’s very easy to get a Singapore tourist visa on Taobao.

BITCOINS: ❌NO

Starting from Jan 14, 2014, Bitcoins, other virtual currencies, as well as mining machines and mining tutorials have been banned.

iTunes Gift Cards: ❌NO

iTunes gift cards were banned on Feb 1, 2017. The alleged reason was that there were too many fake cards, which led to lots of customer-seller disputes.

MANNED AIRCRAFT DRAWINGS: ❌NO

New terms were added on Jul 25, 2017, to ban selling manned aircraft, aviation components, and model drawings, which are classified as general violations.

ANIMAL CROSSING MONEY: YES

Although you can’t get the Animal Crossing game, you can buy money and items to use in the game.

ELECTRONIC CIGARETTES: YES

“Dianziyan” (e-cigarettes) were banned on all shopping sites in 2019. But if you change it to “dianziqiyan” (electronic cigarettes) or the brand names, you will see a lot of choices.

MICRO MONITORS: YES

If you search “mini spy camera”, there won’t be any results. But change it to “micro monitors”, and you will have some options. Most people seem to use them at home, but who knows?

LIVE LLAMAS: YES

You can buy live llamas, maybe because Taobao has some insight into the breeding industry, and thus is well qualified to review the products.

ACADEMIC PUBLISHING: ❌NO

Since May 23, 2018, writing academic papers, thesis projects, and homework for others has been classified as a serious violation.

TAOBAO SHOPS: YES

On Taobao, you can buy Taobao shops, pay professionals to help you decorate your shops, and learn tricks to attract more customers.

Simon: I’m pretty confused by the possibility of buying live animals on Taobao. For a while some friends and I were sending back and forth listings for Tugou (土狗, a common breed of dog) in Guangxi as a joke, because the price was something like RMB 45—we were unsure if shipping would be more than the price of the dog, or if, more darkly, the dog was intended as food, not friend.

Krish: There's a really interesting playbook on Taobao for sellers of dubiously legal goods, not too dissimilar from how community in underground culture works. If you're selling, for instance, laughing gas, or live feed for unusual pets with specific diets, there's elaborate codes for discovery and obfuscation. The "vendor clickbait" that Aaron mentions in the intro has an opposite here, because the goal is to make you ignore these listings altogether.

Taobao is Magic

By Aaron Fox-Lerner

In 2013, the Global Times warned in a headline that “Voodoo dolls [are] nothing but a dark curse on society.”

The accompanying article blamed the supposed trend on young, white-collar women ordering Thai-made voodoo dolls through Taobao.

Eight years later, it’s clear that the ire of state media was far from enough to cleanse Taobao of occult objects. Many of the dolls may be made in Thailand (at least some of the shops advertise them as such), but their vendors are also drawing on long-held Chinese folk beliefs and Taoist religious practices. Often, the dolls are in fact not meant for curses, but to bond couples together. They’re far from the only objects for sale promising magical benefits for the buyer.

With imagery ranging from horror movie-esque dark photos to bright, flowery graphics, vendors offer Taoist talismans capable of filling just about any kind of human need. You can have spells written out in intricate, flowing Taoist script to help you pass a test, succeed in your career, find lost pets, or marry rich.

Sometimes, vendors trend towards the modern, boasting scrolls that can fit in your phone case.

Other times, they market themselves with the traditional: one vendor advertises himself holding up a sign saying “I don’t understand Taobao, I just understand the I Ching.”

And then there are the ones who go stranger. One supposedly Thai practitioner of black magic promises to make buyers taller.

Over murky images of tables laden with skulls and effigies or CGI pictures of a figure with a third eye or a photoshop of a baby in a jar, other vendors make incredible promises: not just preventing miscarriages or conceiving a child, but meeting spirits, seeing into others’ hearts, viewing the past and knowing the future.

Some of the practices may be old and others new, some Thai and some Chinese, but they

all operate on the same principle: wherever people imagine incredible abilities or harbor dark desires, there’s money to be made.

A Summons to Crab Court

By Kendra Schaefer

Kendra: I prefer to steer clear of financial disputes. No matter how badly I’m getting screwed, I almost never ask for refunds. I pay overcharges without complaint, and I don’t contest my parking tickets. It’s not that I’m a pushover. It’s just that paperwork makes me anxious, and I’d always rather lose a lot of money than a little sleep.

For that reason, the idea of ever having to engage with the legal system scares the bejesus out of me. I’m not afraid of going to jail. I’m afraid of spending weeks and months and years in a state of bureaucratic uncertainty, filling out forms, requesting reviews, waiting on decisions that I

can’t fully control. The stuff of nightmares. I cannot imagine an affront serious enough to induce me to file a lawsuit against anyone.

But the architectures of dispute resolution have to exist, if even just for their value as a deterrent. Even if we never walk into a courtroom in our lives — and here’s hoping you never do — the knowledge that the system is there makes us freer to trust our fellows. We can engage with each other with open hearts and wallets, and let those systems bear the burden of our mistrust.

In some ways, Jack Ma made his fortune mitigating mistrust. Chinese ecommerce was born in the early 2000s, when the marketplace was rife with bait-and-switch scams and counterfeit Chanel. Shopping was a hazardous minefield in the best of circumstances, and the idea of shipping one’s money off to a stranger on Taobao required an almost insurmountable leap of faith.

Recognizing this as the primary barrier to their own success, Alibaba tackled the trust problem from more than one dimension.

They launched an escrow service — money wasn’t transferred to the seller until the buyer gave the nod — which later evolved into China’s largest digital wallet, Alipay. They built an algorithmic model for separating the honest sellers from the bad apples, an onboard credit system. And they sunk considerable resources into establishing a dispute resolution platform to handle the cases that fell through the cracks.

Those solutions revolutionized China. Probably also global economics. Point being, Taobao grew, and as it did, it spawned spin-off apps like a wet dog shakes off a bath.

——

One of those spin-off apps, Xianyu, was born when Ali determined that a significant percentage of its users wanted to resell used items. Xianyu is now China’s largest C2C platform for trade in second-hand goods. I love Xianyu. It’s the thrift store to end all thrift stores, the digital garage sale of your dreams, the outlet mall that never closes, the junkyard of China’s runaway consumption orgy. Xianyu is where Shanghai’s wealthy mistresses collect pocket money by offloading the ultra lux clothes they never bothered to try on. It’s where factories get rid of overstock shoes, and where smugglers’ warehouses dump off-the-back-ofthe-truck electronics.

I spend hours and hours there, digging through piles of discarded and unwanted items. Sometimes I get a dud, or something doesn’t fit, but for the most part, the sellers know that profits and honesty go hand in hand, and my experiences have been overwhelmingly positive.

Or they were. Until I bought a shirt off some guy in Ningbo.

Before I continue, you should probably know that the shirt was only 20 kuai. That’s three U.S. dollars. I spend twice that for a coffee without a twitch of concern. But it was never really about the shirt. It was a matter of principle. Nobody likes a bait-and-switch. Nobody likes to be a patsy.

I pulled the thing out of its package. It was not so much a shirt as a kitchen rag with sleeves. “What did you send me?” I messaged the seller. “This isn’t anything like the product description. Different brand name, different size.”

“What do you care?” the seller replied. “A white shirt is a white shirt.”

Look, I get it. Sometimes mistakes are made. Sometimes the material or the color isn’t quite like

the photos. Sometimes the seller talks their product up a little too much. That’s salesmanship. This wasn’t salesmanship. This was an unrepentant highway robbery. I did the unthinkable and requested a refund. The guy denied my request. I requested a return. Request denied. He dropped me another message: “You’re clearly the kind of person who buys things and finds fault with them just to get a freebie.”

“Give me back my 20 kuai.”

“No.”

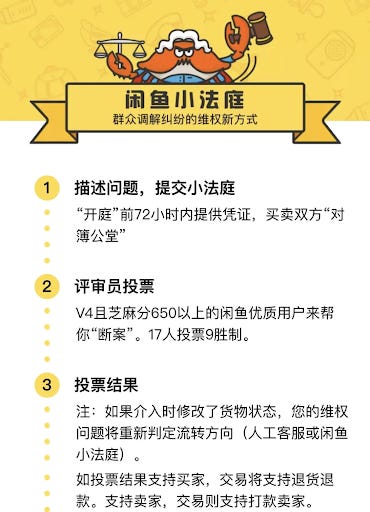

Rage is my favorite motivator. Rage is the get-it-done emotion. Ten years of on-platform purchases, and I’d never dug around in this end of the app. I submitted a request for arbitration, unsure what was going to happen next. Maybe someone from the Ali complaints department would review the transaction history and make a decision. If I was lucky, maybe someone would call me and ask what happened, listen to both sides, issue some kind of judgement. Instead, I got a summons via text message. “CRAB COURT HAS BEEN CONVENED. SUBMIT YOUR EVIDENCE. ”

Crab court. I clicked into the courtroom, and sure enough, there it was: a tiny cartoon crab judge waving a gavel around in its pincers. Both the seller and I were required to submit screenshots and photo evidence of the transaction for adjudication. The interface seemed to suggest we’d been entered into some kind of American Ninja Warrior contest, and that a panel would be convened to cast votes on our case.

So this was the epitome of Alibaba’s 20 years of experience settling conflicts between market participants. They took their zettabytes of trade data and built some kind of Hot or Not deathmatch presided over by a tiny animated sea creature in a powdered wig.

I sent a screenshot to a friend.

“So, can I submit a vote in your favor?”

I didn’t know. I didn’t know who the jury was, or how they were selected. I thought maybe Alibaba circulated the evidence to multiple members of its in-house team, just to keep things fair. Nope. Later, after I’d won the case, I found out that the whole thing is tried in the court of public opinion. Xianyu uses Alibaba’s onboard reputation system to select trustworthy judges from its customer base — other buyers and sellers — then invites them to submit an opinion.

I got my 20 kuai back. I still don’t know how I feel about it, though. I have more questions than answers. Is this what data-optimized justice looks like? Is this a little window onto the murder trials of 2081? Crowd-sourced jury duty mixed with a couple drops of reality TV? God help us. God help us all.

Yan: Krish and I had a similar experience on Taobao earlier this year. A damaged package arrived at our door, and we got caught in an endless loop of complaints: first to the Taobao seller, then to the kuaidi delivery company, then Taobao’s own customer service. Long story short, the Taobao shop wanted the delivery company to pay, but the delivery company wanted the delivery worker to pay. The delivery worker texted me, “My company asked me to pay you. How much is your thing? I’ll pay for it, and I’ll never work in delivery ever again.”

We found it unfair and exploitative for a delivery worker to take sole responsibility for an issue that either the shop or Taobao platform could easily cover (the brand we bought from made $50 million in profits last year). We told the delivery worker that he shouldn’t pay, and asked for mediation. In the end, after numerous hours on the phone and multiple message threads, Taobao compensated us directly. It took us four or five days to “solve” the entire problem.

Krish: The whole issue was grounded in this rigid flowchart of behavior and responses at every level, a closing of ranks and shirking of responsibility. This left the delivery worker as the sole “agent” on whom to pin blame to. His text to Yan made us wonder how normalized this was, and how many delivery workers had to personally pay off the cost of damaged goods.

Yan: Like what Kendra said, the infrastructure is there to mitigate incidents, because, by the end of the day, Taobao wants customers to trust them. They cannot survive without a diverse range of shops, reliable delivery partners and loyal customers. So they were willing to pay from their own pocket (almost like hush money) for my damaged product. However, systems of responsibility, and the physical and emotional labor that goes into it, seem to be seen as someone else’s problem: passed down all the way to the customers.

Tianyu: That’s it for this special crossover episode! If you enjoyed this, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription, or forward it to a friend by hitting the shiny button below! All of our revenue will go towards paying contributors on time and supporting writers. We also welcome feedback, story ideas, and cute animal GIFs via email (hello [at] chaoya.ng) or Twitter (@ChaoyangTrap).

Krish: One last thing before we go.

If you’re in Beijing, we’re organizing our first movie screening! Mark your calendars for the evening of Sunday the 4th of July, at fRUITYSPACE.

More details later this week, but this will be the film’s China premiere, and it will be followed by a (Zoom) Q&A with the director and cast. It will also screen online for a week, watchable from anywhere.

——

Outro music this week is a new Cantopop mix by friends of the newsletter 工工工 (Gong Gong Gong). It was part of opening day programming at Baihui, a new online radio station started by DJs Knopha, Slowcook and Frau. They’re great, it’s good, and the canto drops at 00:01.

Tianyu: Bye!

Sasha Fominskaya is a Beijing-based Taobao addict and graphic designer.

Aaron Fox-Lerner is a writer, editor and game designer based in Beijing.

Kendra Schaefer is the Head of Tech Policy Research at Trivium China. She, like the rest of us, over-consumes.

Joy & Josh are a creative duo based in Beijing. They make zines,collages and other art works from their experiences in the shapeshifting city.

Tianyu Fang likes to collect train ticket stubs and boarding passes.

Jaime (bot) works in Chaoyang and has moved to Chaoyang.

Krish Raghav is a comic-book artist in Beijing. All his comics were printed on Taobao.

Yan Cong is a Beijing-based photographer. She hoards Taobao shop memberships and coupons.

Simon Frank is a writer, editor, and musician/slob otaku human based in Beijing.