Season 1 Epilogue: Chaoyang Trap Reacts to Chaoyang Trap

Reflections on Season 1 + New PowerPoint Reveal + The Joys of Shared Pessimism + Attack and Dethrone this Substack + Dayyta Sienssss

In the house this week: Tianyu, Jaime, Krish, Caiwei, Christina, Yi-Ling, Ting, Simon, Amy, Carwyn, and Henry.

Krish: Hello.

Tianyu: Well, we’ve finished an entire season, and we’re still not a podcast.

Jaime: Should this be a podcast instead?

Krish: Even better. It’s going to be a PowerPoint.

Tianyu: …

Krish: Welcome to our Season 1 Epilogue. We thought it might be interesting, maybe even useful, to reflect a little on our first 10 episodes. Or, as a bot legend recently put it: “What have we done?”

Also, and this is the “useful” part, how did we get here? What might other newsletters hoping to attack and dethrone Chaoyang Trap need to do?

Part 1: “What Have We Done”

Krish: So this is like a really vulnerable moment for me, but here are some of the actual PowerPoint slides I made when pitching this project to everyone here.

The genesis of Chaoyang Trap was just a group of friends whose ambient disquiet about the state of culture writing in China was channeled through the magic of a slide deck.

Tianyu: I remember sitting down with Christina circa 2017 in Beijing near Dongzhimen, and she brought up the project she was working on with Tricia Wang and Pheona Chen that later turned out to be Magpie Kingdom. It was so fundamental to my understanding of English-language content about the Chinese internet.

Krish: Tianyu and I originally just wanted to reboot Magpie Kingdom, but everyone involved had forgotten their social media passwords (and been kicked out of Medium for “suspicious activity”) so we had to start over with a new name. I’m not saying we don’t regret the name Chaoyang Trap, but we’re all… pro-rebrand if anyone has a better idea.

Krish: Looking back, we used the word “cursed” a lot to describe our view of the status quo, and I think we were referring to 1/ the “trap” (lol) of needing to write about contemporary culture in China as always “partial, belated or emerging” and 2/ an artificial divide between flawed definitions of “local” and “foreign” that led to misguided exceptionalism and blindness to non-”western” connections when talking about trends, styles, or memes.

Jaime: Chaoyang Trap is a series of traps to begin with. How do we define the “Chinese internet”? (It already sounds weird if we say “the internet that people in China participate in” since that sounds like we are not part of this internet, or that this internet doesn’t include people other than “Chinese.” I’m overthinking semantics, clearly, but.) We are not really a collective. We are certainly not all Chinese, although it’s safe to say that all of our contributors have invested their lives in China or Chinese culture in different ways and degrees. Maybe we are “local” at best, but even that rings false in some ways.

The fact that I had so much doubt about what gives us legitimacy to write about China is partially a result of how much explainer journalism has poisoned the way we frame our thinking about writing about cultures, and partially a result of how the media environment in China has poisoned the practice of journalism itself. In a more innocent time, the role we occupy might be closer to “blogger” than “journalist.” You can get very petty and technical if what qualifies a person to write about another culture is like adding up points on an immigration qualification questionnaire. Do we trust this journalist more if he’s white but he’s lived in China for twenty years and speaks almost fluent Chinese? What about a Chinese kid who has just returned to China from living in America their whole adolescence, but with deep family roots in Beijing?

So in some ways I wanted to think about how doing this newsletter is freeing us from this kind of identity-based thinking that has become so toxic in media literacy. The legitimacy issue came up the first time we were plagiarized by a prominent Chinese outlet. That’s when I realized, oh shit, people are actually paying attention and taking us seriously. It’s not just a bunch of us who spend too much time on the internet. We started asking more questions about the nature of the newsletter. It’s easy and necessary in the beginning to go in with an attitude or a sensibility: well, we are gonna do better than all these other publications that we are dissatisfied with, but now we should actually define these practices and the integrity that is supporting what we put out other than simply being reactionary.

Krish: “Accomplishments of analysis are paid for with a dissipation of synthesis.” I guess we organically realized that our grift wasn’t “explaining better” but “synthesizing wider,” hence the group chat format.

Yi-Ling: I remember when I first returned to Beijing, being incredibly underwhelmed by writing about the internet in China—so “cursed” as the Chaoyang Trap community has introduced to my vocabulary, in other words, so monolithic and reductible, so rooted in this gaze of 21st century digital Orientalism, sucking the fun and the humanity out of it all.

Around the same time, I stumbled upon a quote by Virginia Heffernan that gorgeously articulated the lens/attitude with which I wanted to make sense of the Chinese internet (perhaps slightly more rose-tinted/techno-optimistic of a perspective than I have now):

“The Internet is play, is expression, is challenge, is a call to greater eloquence, grander originality, most expansive community and shrewder gameplay.”

I am grateful to Chaoyang Trap because it has provided that: a space to play.

Caiwei: Speaking as a writer in English who grew up in China, I think Chaoyang Trap is this rare opportunity to meet readers halfway between the nuances of the Chinese web and “internets” elsewhere. You can go fine-grain rather than heed the usual editorial advice of “zooming out.”

Like every other field in arts and humanities, journalism has a “western-centrism” problem, and reporting on China has long been part of perpetuating that. Writers are usually expected to bridge the vast knowledge gap between China and a presumed English-reading audience, to explain the most mundane subjects in the most laconic way possible. Bearing all the responsibility of contextualizing usually means a flattened, highly reductionist version of reality that often goes around unexamined.

Tianyu: China reporting as foreign correspondence, after all, retells one group’s stories to another audience, but that isn’t enough. What are the boundaries between reporting and dialogues? And how do we turn one-way explainers into two-way conversations? What we want isn’t just storytelling, but also mediation.

Christina: When I first started writing in English about the Chinese internet, I had one major epiphany: I could manifest my ideal audience into being by simply creating for them. This doesn't mean that I write so well I instantly transfer my experience and values into someone else!! But rather, that it could be a powerful act to trust that there were people who cared about the same things I did with a similar need for something more than the 101, even if no editor believed they existed in large enough numbers to matter. Everyone else, I figured, would actually appreciate getting a glimpse into a conversation that wasn't necessarily meant for them, but provided enough on-ramps that the truly invested could follow along with a little bit of effort.

We got some of that right with Magpie Kingdom: letting the natural flow of the Chinese internet dictate our topics; illuminating patterns by telling stories from the edge; underscoring both the fundamental differences and similarities between the English-language social media ecosystem and the Chinese.

The thing I am most grateful to Chaoyang Trap for is its full embrace of that original epiphany. Its true clubhouse format makes it so much easier to NOT second-guess that feeling of trust—if there are a dozen people inside the clubhouse already, we can be sure there are more outside just waiting to be written for.

Krish: This discernment, this exercise in listening rather than explaining, was important to us. Outside of academia, a lot of culture writing on China in English is pure 101 "context translation," a necessary but perhaps overrepresented genre. We wanted to push ourselves to frame stories and make connections that would be surprising even to the extremely online within China. I’m not sure we succeeded entirely either, but part of that approach was to see “trends” not as neat, uncontroversial histories, but rather as messy, tangled knots of material and social circumstances.

I think the season finale, on wanghong urbanism, really encapsulated that approach.

Carwyn: The Chaoyang Trap Group Chat Format™ made sense to Amy, Asa, and me as the idea of wanghong urbanism began in our Twitter DMs over a year ago. It was one of a number of ideas we were throwing around in the DMs, and the only one that seemed to stick, probably because it was fun, would be seen as shallow by others but was full of D E P T H. Transitioning from Twitter DM to Chaoyang Trap format happened through a Google Doc, and the first line of that Doc was: “Treat this like DMs.”

Amy: When I was tweeting about the wanghong urbanism episode, I thought about saying something like “we are opening up our Twitter DMs.” This continuity between our Twitter DMs and Chaoyang Trap Group Chat Format™ definitely helped the writing process.

More importantly, I think this conversational way of writing made working on this project an enjoyable and ”flowy” experience. We were able to work both independently and collaboratively, expressing our own opinions, responding to each other, while being fine with presenting tensions and disagreements among ourselves, whereas a more “conventional” format would require us to reduce into one coherent voice. Being able to write in this way was particularly helpful for us at this stage as we were still working through initial ideas about the wanghong urbanism phenomenon, and a more “open” format that allowed each of us to articulate what we see was exactly what we needed.

Carwyn: Whilst stalking the Chaoyang Trap Twitter for mention of our episode (Tip: Best way to get loyal viewers is asking them to write for you), I saw something that Joshua Minsoo Kim, of Tone Glow, said that I really agree with: Chaoyang Trap is “like podcasts without the worst part of podcasts: hearing people talk at length ineloquently.” I agree with Joshua as both a viewer and a contributor. My worst fear during public speaking is being asked a question I don’t know the answer to and then saying something long and very, very wrong. This format gave me the chance to have fun, to write without fear, and then delete all of the nonsense.

Extending the format beyond Chaoyang Trap, I have previously pushed for overt, dialogue based writing for academic purposes, but received strong ಠ_ಠ vibes. This experience resulted in me bringing up the subject a few more times. Let’s see where it goes.

Part 2: Data Science and “Insights”

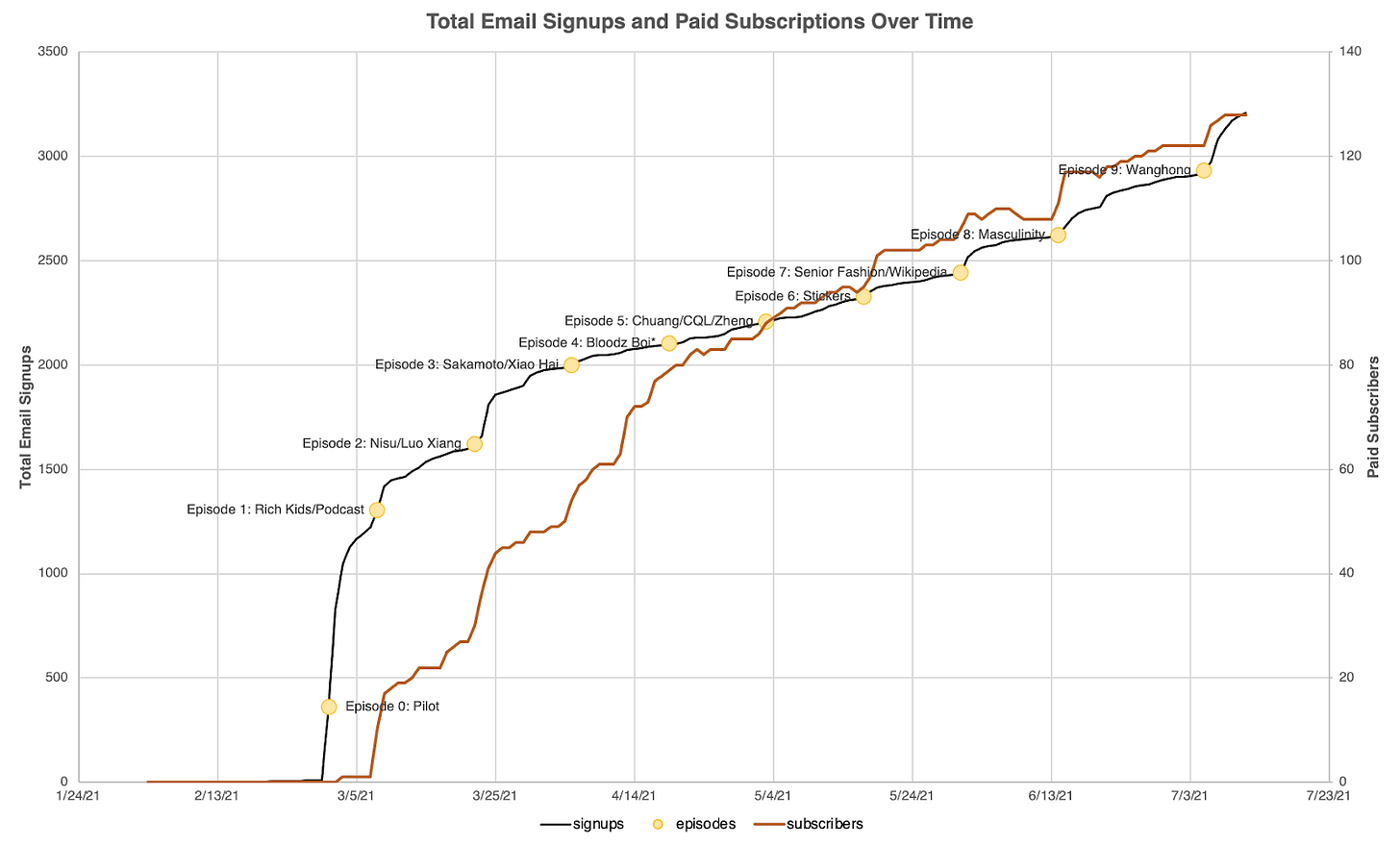

Krish: We had fairly modest expectations of what counted as “success,” and it’s been really humbling to see just how quickly these milestones were surpassed:

We’re currently at 3,350 subscribers, of whom 160 are premium subscribers. This is enough to fund two full 10-episode seasons of Chaoyang Trap with a 500 RMB (~75 USD) fee for every article and illustration. One of our big goals is increasing what we pay contributors for Season 2—ideally a baseline of 800-1000 RMB.

We spent a little over 9000 RMB (~1400 USD) on Season 1, broken down into the two genders:

This initially came out of our personal savings, but we made that back within the first four months. All commission fees and incidentals now come from the “company account.”

Here’s Tianyu with some more dayyta siensss.

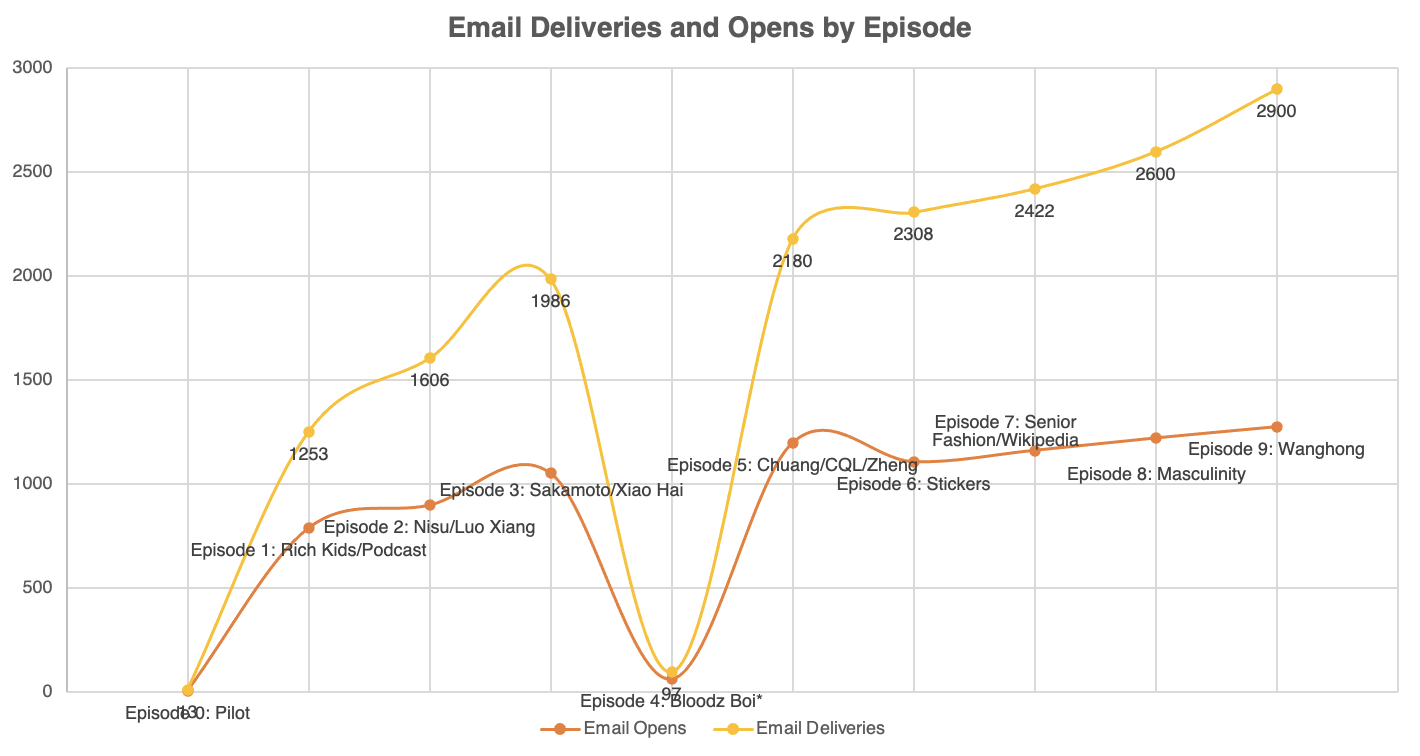

Tianyu: We started Chaoyang Trap thinking that we’d adopt the freemium model of paywalling bonus episodes. We sent out Episode 4, an interview with the Beijing-based musician Bloodz Boi, as a “deep dive” dispatch to our paid subscribers.

It was clear to us that the model didn’t quite work. The episode didn’t get the attention it deserved. Besides existing paid subscribers, it had few retweets; there were few conversions. Even by Episode 4, we had been accustomed to having thousands of views and social media interactions with readers. It’s difficult to feel the same kind of excitement when our work is only visible to a hundred subscribers.

This would have been fine if we were seeing the exclusive episode as a way to reward our paid subscribers. But we realized that subscribers aren’t paying us for exclusivity. They support us to keep Chaoyang Trap going. They want—as we do—more people to read what we publish, not fewer.

Simon: Wow, seriously, justice for Bloodz Boi.

Krish: Twitter was, far and away, our number one source of discovery and engagement. The “group chat” format helped. A combination of personal tweets meshed with the Chaoyang Trap group account meant we could highlight every episode from multiple angles. We took inspiration from collectives like Chinese Storytellers and consistently boosted non-CT work by our contributors.

Tianyu: A few landmark events brought us traffic: being featured on Metafilter (twice!), link outs on Marginal Revolution and Naked Capitalism, and two very generous shout outs on Garbage Day. One other landmark event brought us joy: being mentioned by CT-favourite Joshua Minsoo Kim on The Cut.

Krish: The Metafilter and Garbage Day mentions, as well as features in Sinocism, SupChina, RADII, and China Neican, were among our biggest source of new followers and subscribers. “Celebrity endorsements” like Marginal Revolution or Kevin Kelly bought traffic but not signups.

Part 3: Who are Our Readers?

Krish: We have a miraculous, funny, empathetic, attentive audience—a real dream for any publication, an unimaginable honor for our small group project.

We average around 5,000 views per episode, and there hasn’t been a day since we launched without new subscribers. This is who we expected would read Chaoyang Trap:

This connects to what Christina said earlier about manifesting an ideal audience. We did second guess ourselves, forgetting that the ideal readers were, first, all of us: as friends, as mutual conscience keepers. I keep thinking about Alexis Ong’s recent piece on the “radical editing collective” Racer Trash, where she talks about this joy in being supportive about something created as a group. About “banding together instead of competing over the same scraps.” A project as a gift.

Ting: I tried to approach my nisu piece in a way where it felt like a 2AM text rant with a friend that begins with "okay, there's this Thing and i have thoughts" and ends with "or idk, maybe i'm just sleep-deprived, what do u think." Having everyone in the house as an ideal audience not just to write for, but in some way to win over, made it easier to make better decisions: you're being supported, but also gently/meaningfully challenged.

Carwyn: Writing communally is joyous. I spend so much of my time slaving away over 10,000 word manuscripts and second guessing myself. Most of this is an internal fight, and it is both validating and inspiring to sit down with like-minded people and see where the text goes. There will always be fear of critique, but the way in which our roundtable article unfolded made critique unthreatening. Our engagement with wanghong urbanism is in its early stages, but the collaborative process WE engaged in was productive and refreshing.

Amy: I can echo what Carwyn said about second guessing oneself and the fear of critique (both Asa and Carwyn have been on the receiving end of my endless self-doubt—sorry/thanks guys!), which are probably common side effects that academia gives people. But the joy and fun this writing process gave me helped deter most of the doubts and fears that come with producing something to be scrutinized by others.

I enjoyed reading the reactions and responses the episode generated on Twitter. I am not sure if I should feel surprised that our episode did not seem to ignite much interest from other academics in anglophone urban studies, which perhaps indicates the values assigned to different types of writing in our field.

Jaime: The sad reality of our transient lives in an increasingly inhabitable place means that we often don’t know how long we will stay here or where everyone will be in the near-to-long-term future. Some of this latent anxiety is reflected for me in the structure of self-contained “seasons” as a result of this sense of built-in precarity—yolo by any other name. I think we would’ve been a very different publication if we were building for longevity or legacy. (Do you trust a can of fish without an expiration date?) It is this alchemy of desperation to be understood (not to be mistaken for represented) and finding that understanding in communicating what touches us that I think makes the newsletter come across as “authentic” and “down to earth” or whatnot—the stuff media VCs love to fetishize because it is actually so counterintuitive to orient yourself this way in normal capitalist society. There literally is no profit model for kinship. Like Christina and Tianyu mentioned, there is an act of translation here that is more than trafficking cultures and ideas, it’s also mediation and—I am using this word for the first and last time—care for what and who we know and see, because we do have the privilege of seeing more and reaching more by the virtue of our positions as bi/multilingual transnationals. And this is something worth celebrating, despite the challenges and perpetual existential crises. I love this definition of joy from Carla Bergman and Nick Montgomery’s Joyful Militancy:

"Joy rarely feels comfortable or easy, because it transforms and reorients people and relationships. Rather than the desire to exploit, control, and direct others, it is resonant with emergent and collective capacities to do things, make things, undo painful habits, and nurture enabling ways of being together."

Countering extractive journalism, if anything, I would be proud if we have reoriented (re-orient lol) ways of how people think about “China coverage” and community-based journalism.

Krish: For me, a part of this “reorientation” that Jaime mentions came out of a painful personal realization. I had this persistent...saltiness that many in the traditional “China watching” sphere, including mentors and senior figureheads, did not (or could not) care for this newsletter. Much of this was an overreaction, my Twitter psychosis.

Stepping away from this question of “who didn’t read us” as a kind of petty score-keeping, and towards a more inclusive “who else can we bring into this” was really rewarding.

Carwyn: In all honesty, from behind this pair of rickety old Panjiayuan glasses, the broader (English language) China Discourse seems to be a cesspit unfit for human habitation. It is definitely not good brain juice for anyone, and drinking that juice produces painful discord. More honesty: I have stopped reading anything that isn’t recommended to me by someone I respect, or, at least, trust. I am so tired of reading information reported about China (or other topics) that is just a vessel for incestuous, ideological warfare. And I am not just talking about U.S. newsrooms here. I hope I’m not being naive, or have accidentally swapped those Panjiayuan specs for a pair of rose-tinted ones, but it feels like things have gone downhill. The current discourse is as often about China as it is about using China in ways that are always one misinterpretation away from violence.

Amy: I have long refrained from participating in or subjecting myself to too much China Discourse because it is indeed cursed (to use the Chaoyang Trap vocabulary) although sometimes such efforts inevitably fail as a Chinese person who does research on China and has been on Twitter for more than a decade. So I do not claim to have any clear or accurate grasp of what the broader China Discourse is like, but I do feel that as a field (is this a proper word for it?) it has become increasingly performative, serving more for the purpose of personal branding than anything else.

The few pieces and discussions that I have found helpful or productive in the broader (English language) China Discourse are less about presenting, explaining, or reinforcing an orientalized other to a western audience and more about responsible analysis of and reflection on the meanings and implications of China-related issues, but they are not the loudest components of the Discourse.

Simon: I guess in some ways the shared pessimism of the Chaoyang Trap community makes me slightly less pessimistic about some things. Looking at many issues in the world today, it is somehow easy to lose sight of the realization that “this [problem or incident] is quite absurd and actually quite sad.” Especially in China Discourse, it can seem like the only modes are tech-optimism, and knee jerk negative reactions which leave a bad taste in your mouth even if they happen to be factually accurate. Being able to participate in discussions with a more nuanced negativity (haha) has personally been really rewarding for me.

Carwyn: Earlier, Jaime mentioned the roles of “blogger” and “journalist.” As neither of those, I feel that the boundaries have changed. In many ways the Chaoyang Trap content goes above and beyond journalistic content. That could be expected, as Chaoyang Trap is a slow burning labour of love made by a group of culturally aware people. But maybe it also fills a void that has emerged since News Journalism became the Opinion Section, with cursed comments slid in amongst a description of events. Or, since journalism stopped being professional (ethical lapses or abandonment, defunding local reporting, clickbait) and blogging became a profession. For me as a reader, Chaoyang Trap is providing much needed nuance, criticality, humanity and alterity, four of the many things that are lost as reporting becomes black and white.

Amy: Being critical but also nuanced and responsible is not what most of the Discourse is like and many perhaps do not have the patience or appetite for such content. But it needs this kind of valuable and meaningful intervention.

Ting: An example of that intervention is resisting the kneejerk urge to use words like “subverting” or “queering” when writing about subculture, which I think prevent us from identifying the tensions present. I think one approach of Chaoyang Trap that I especially value is instead of stressing how a particular internet trend is completely new (which makes it more newsworthy), we take the time to trace its precedents, to show how this trend *is* in some way a product of its very particular environment.

I also think often the problems I have with journalism on Chinese culture isn’t necessarily with content, but with structure (This Thing is Now A Thing - Some Context - It Has Impact - They’re Being Censored). Threading information is building narrative, and I appreciate the way our group chat format allows for a dynamic structure so that it never feels like we’re writing the same story with the subject matter swapped out.

Some other publications later wrote about nisu too, and for me some of those pieces had problems that show the difficulty of covering a niche subject when you’re not sufficiently immersed—for example, quoting a well-known voice in the community and reducing it to “one weibo comment.”

Krish: This is perhaps a good segue to the last big question haunting us after one season: what could we have done better?

Part 4: What Could We Have Done Better?

Tianyu: We started out hoping to give agency to people whose voices have been left out by the existing English-language landscape. While I think we’ve shown there’s an alternative to the current “China internet” coverage, there’s much room for us to involve Chinese creators and readers in this work. This could mean welcoming Chinese-language content—we can translate writings into English, as we’ve done for interviews—and making Chaoyang Trap newsletters visible and accessible to local communities.

Jaime: For me, the hardest story we published was Caiwei’s deep dive on three male self-help kings of their respective niches, the story with our widest reach to date. Chinese masculinity was something that we had been talking about for a while and I was excited that Caiwei was committing herself to listening to hundreds of podcast episodes and asking the subjects difficult questions (such as, “how do you reconcile your status as a Jordan Peterson disciple with being a feminist and queer ally?”). I knew she was the perfect writer to take on a topic that requires as much research into unsavory territories as it does level-headed compassion and nuance that comes with a big-picture understanding of the gender discourse landscape and particularities of this Chinese public sphere.

Caiwei: As someone who calls herself both a “writer” and a “journalist”, I definitely stumbled between the edge of both lanes when writing for Chaoyang Trap. Deciding what to write was a pleasant head rush, as the process usually took place during a friendly dinner or drinking session instead of the usual email exchange or editorial meeting. The unconditional trust placed in me by my friends led me to take on tricky subjects I am deeply invested in but would never have pitched to another publication, simply for a fear of the editorial gaze of “why is this worth writing about” and the “why should I be the one writing about it” that would inevitably follow.

As a result, I tend to indulge myself to a certain degree of “genre merge”, and if I have to find a term for this format of writing, it might be somewhere on the “gonzo journalism” spectrum. The practice has thus caused a series of ethical interrogations for me and the group — if what I’m doing improvises outside of journalism, how much ethical and creative burden should I bear for it? The dilemma felt especially disquieting when working on the masculinity piece.

Jaime: Caiwei returned with a sprawling first draft, and we immediately wished that we could have the resources to do a real investigative cover story. Despite obvious fourth-wave-feminist problematiques at first glance, the three profiles contained way more layers than shoehorning each into their rough Western equivalents. Still, it felt somewhat of a departure from our previous stories—for one, we were nervous about how it would be received by the subjects themselves. Prominent figures are not accustomed to being criticized at arm’s length in Chinese media, and the piece belonged to a different kind of engagement than our previous interviews.

Things got murkier once the draft was ready for other Chaoyang Trap contributors to enter the chat. It became less and less clear if we are criticizing the issues of spineless, low-bar masculinity standards, or the figures themselves, who fwiw should be dealt proper criticism as peddlers of these ideas we disagree with.

Krish: This was the group chat format at its messiest. In a critical piece like this where the author has “done the work,” bringing in “reaction” voices undermines a carefully constructed argument. I, for one, regret some of the comments I made there as comic relief—it felt like heckling from the sidelines.

Caiwei: When read together with the comments, the piece is not flattering, and the main characters are aware of that. Having brief personal interactions with all three of them (two cooperated actively with my interview requests), my respect for their work grew. I wouldn’t go as far as saying I am “in favor of” the ways they present themselves, but I think it is fair to say (as I recognized in the article) that all of them represent a somewhat progressive stance on masculinity and gender dynamics, especially within the deranged universe of the Chinese internet. In retrospect, I wish that I’d made this point clearer in the articles, that being the “manfluencers” they are takes a far above-average level of sophistication, originality and enterprising spirit.

Jaime: The dilemma came down to a question of genre: if the piece has been conceived as profiles, then the comments sound increasingly like personal attacks; if the piece is a topical investigative, then the angles of these three profile vignettes should be reoriented as an issue-based op-ed. The piece would’ve also been fine as a “voicey” op-ed, too, but I do feel these conversations should be a two-way street rather than a one-way extraction of fulfilling curiosity and woke superiority. It wouldn’t sit well with us to run a story that we would be hesitant to show our subjects after the fact. There are, of course, methodological ways to deal with this in more traditional forms of journalism, but these new demands of cross-cultural ethics is where we—as humans first, writers/journalists/documentarians second—are still feeling our way through in the dark.

Caiwei: The skeptical perspective from which my observations were made are certainly personal but I found myself holding these three characters to a standard that neither them nor their fans have bothered to (at least in public). Where do these “new men” stand, on a bigger political spectrum or on multiple social issues, with their western counterparts? What are their trajectories of change and growth like? How do they package progressive ideas to find a Chinese market? How do they reconcile the seemingly inconsistent discord in their words and deeds? With questions that were both “zoomed-out” and “fine-grain”, I was happy with the scope of the piece, which allowed me to do a detailed three-part profile instead of one concise umbrella piece that would likely contain (over)generalizations and equally (if not more) controversial assertions. The length and space was necessary, allowing me to follow through on my own investigations and justifying my observations.

Krish: That’s it for Season 1. We’ll be back late-September with Season 2, when regular fortnightly service will resume. Thanks for reading, and thank you for sticking with us. As always, feel free to email us if you have any feedback, and a tiny reminder that we remain open for pitches and stories!

Outro music is two of our favorite bands from Henan, reeling this last month from extreme flooding and unprecedented rain. Both these bands have been at the frontlines of flood relief in their hometown of Xinxiang, contributing to rescue teams and helping fundraise for supplies.

Muzzy Mum (麻兹妈) play cold, clinical, nervy post-punk in the P.K.14 or Hiperson mold, and this single off their latest album (with an eerily prescient cover) coils with the same rage and grief that many in Henan are feeling right now.

Pumpkins (小南瓜) have a dark, central-Asia inspired psych rock sound, and I love this surreal music video about leotard-clad wrestlers fighting for survival.

Tianyu: Bye!

Tianyu Fang was a Beijing transplant in New England, but he’s moving to California. His website shows up if you look up “Chaoyang Trap” on Baidu.

Jaime (bot) works in Chaoyang and has moved to Chaoyang.

Krish Raghav is a comic-book artist in Beijing. He really wants some aloo tikki.

Amy Zhang is from Chaoyang and now works in Manchester. She is in need of a new pair of glasses from Panjiayuan.

Caiwei Chen is a writer, journalist and podcaster. She is excited to become an owner of pretty bay windows in her new apartment.

Carwyn is a Manchester based academic who is yet to arrive in Manchester. He has recently written about dynamic stillness in Beijing.

Yi-Ling Liu is a writer in Beijing. She believes deeply in the importance of spinal integrity & flexibility.

Simon Frank is a writer, editor, and musician in Beijing. His new album So Dream It is out now on Absurd TRAX.

Henry Zhang is a writer in Beijing. He believes in life after love.

Christina Xu used to write about Chinese internet culture, but now mostly yells about and on the American internet.

Ting Lin is a writer in Beijing. She has very vivid nightmares about goldfish.