Far & Near x Chaoyang Trap: Lockdown, Normalized

Stories from the Shanghai lockdown: PCR test body horror + “Run P.R.C” + quarantine hotel pop-up concepts + Voices of April

In the house this week: Beimeng, Charlotte, Yan, Camden, Lisha, Tianyu, Henry, Krish, Emily, ████, Xuandi, Yi-Ling and Simon.

Krish: Hello. This episode of Chaoyang Trap is a little bit different.

Far & Near, our favourite Substack, put together a roundup of stories, artwork, and photojournalism emerging in response to the Shanghai lockdown, and we felt it was important to amplify and co-promote.

The COVID control measures adopted in Shanghai have resulted in tragedy, rage, confusion, and anxiety. Here, Beimeng, Charlotte, and Yan bring us a cross-section of dispatches from the city: photo essays, performance art, video collages, and howls of anguish from residents seemingly stuck in an endless present.

Beimeng: It’s Beimeng writing from Shānghài.

I’m counting my 28th 29th day of home quarantine, after three rounds of government food supplies, one delivery of Lianhua Qingwen, four rounds of PCR tests and dozens of rapid tests. The city of 25 million residents is under strict lockdown amid China’s latest COVID outbreak, with no end in sight.

Two years after Wuhan’s re-opening, a historic moment that I witnessed in person, the once unprecedented is becoming normalized: according to Caixin, at least 22 cities in China are currently under some form of lockdown. In some cases, one local infection is enough to guarantee citywide closures.

What’s different about the 2022 lockdowns is that, rather than COVID itself, people fear food shortages, centralized quarantine facilities, family separations and non-COVID medical emergencies. Social media posts that carry direct, raw audiovisual evidence documented by patients, protesters and homebound residents play a key role in questioning China’s zero-COVID policy. The panic has a ripple effect: as Beijing reported its own community transmissions this week, residents jumped into action, clearing supermarket shelves despite government assurances of abundant supply.

If there’s one thing people in Beijing have learned from Shanghai’s 4-day-turned-indefinite lockdown, it is this: be self-reliant and don’t trust what the authorities say.

In this special issue, Charlotte, Yan and I would like to compare mainstream and social media coverage of the lockdown, and highlight some of the most memorable sounds and images that made the rounds before censors zeroed in.

Our work is sustained by reader donations. If you like this newsletter, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and telling your friends about it.

Charlotte: There have been a few good works that cover the chaotic logistics of lockdown and how residents are being affected. For example, this video about truck drivers stuck in Shanghai after delivering goods to the city highlights how the suppliers were themselves undersupplied, and had to live in their trucks for weeks, running low on food. Another story is this beautifully photographed visual diary of Zhou Xin, a Shanghai photojournalist who documented her quarantine time spent stocking up food, cooking for her two children, and growing her own scallions in flower pots.

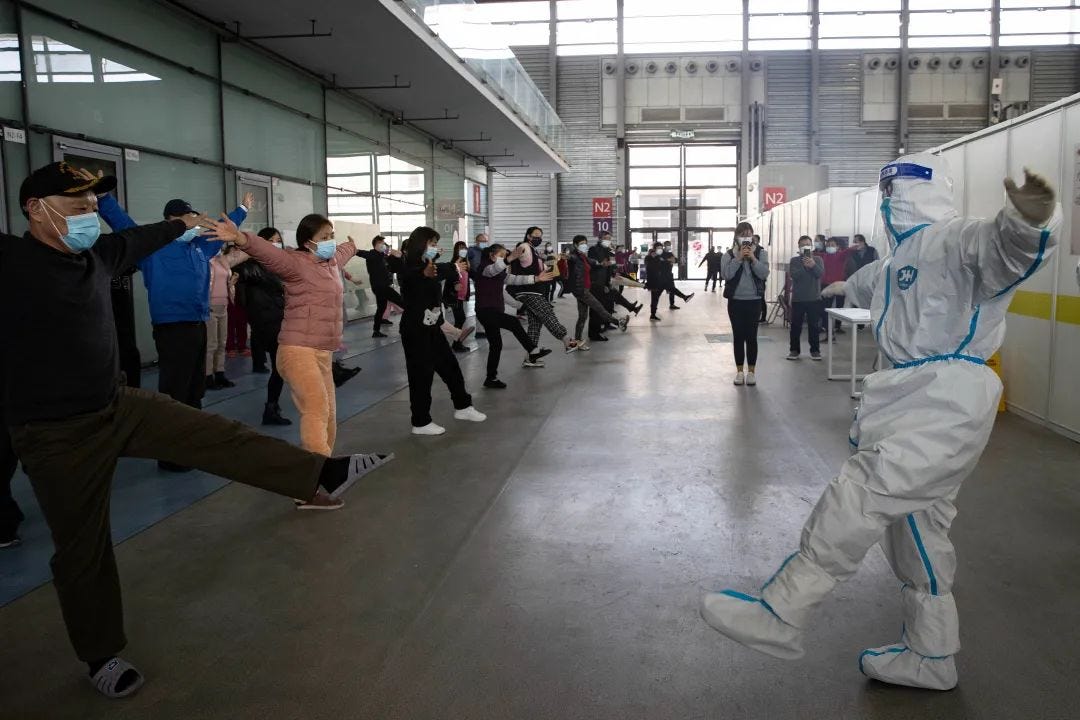

China’s mainstream media has focused on softer, less critical stories. Take, for instance, the coverage of Fangcang—mass quarantine centers for people who test positive but display mild or no symptoms. Stories from official and mainstream media are in stark contrast to what people have been saying on social media.

Beimeng: Written stories and uploaded videos from patients revealed difficult living conditions: constant noise, 24/7 lights, a lack of privacy and access to medical care. In some cases, patients in some of the hastily built structures have used tarps, cardboard boxes, washbowls, and anything else they can find as makeshift shelters under leaky roofs. The centers are rife with irony: in one widely shared video clip, a group of patients who seem perfectly healthy rescue a doctor passed out from overwork. These images reach a panicked, social media-addicted population in lockdown, their authenticity rarely commented on by mainstream media.

Access, Witness, Coverage

Charlotte: Lai Xinlin, a photographer working for Jiefang Daily, the official newspaper of the Shanghai Communist Party, received rare media access to Fangcang. The photographs he later published showed a much more organized, calmer side of the quarantine centers, contrary to patient accounts. Lai acknowledges the difficulties patients encountered in the article, such as the lack of showers, and the fact that thousands of people had to share a small number of toilets that were often clogged. But we don’t find these scenes in the final, published story. What he shows is rather routine and even encouraging—young children quarantining together with parents, students prepping for exams, and medical workers exercising with patients.

Some Chinese artists and critics lambasted Lai’s coverage as propaganda, arguing that he had deliberately focused on showing the positive. But many photographers came to Lai’s defense, making the case for his photos as objective and his work as valuable. Some called for understanding and tolerance, speculating that he took more photos but could (of course) only publish the less critical ones due to censorship in state media. Lai himself said he’d rather not respond to the controversy but just continue to focus on his work, and let it speak for itself. The discourse around Lai’s photos raise interesting questions for visual journalists operating in restricted media environments—should one take advantage of rare access in exchange for positive coverage, because otherwise, no one will bear witness? How far can one compromise before the work is no longer journalism but something else entirely?

Beimeng: I’m reminded of the late Cultural Revolution photographer Li Zhensheng, who was assigned to capture propaganda imagery of official events but for years secretly kept undeveloped negatives of the political campaign’s dark side. Li’s works wouldn’t have been recognized in the same way should he not have taken risks: pointing the camera at the sufferings, making public the fuller collection of his photographs. He could have remained another propaganda photographer.

Xuandi: I was especially saddened by photos that captured the “delights” of Fangcang, such as children and seniors exercising with smiles on their faces. It just shows how easily we can compromise and settle when faced with grief and quickly move on from contemplating what got us there—how absurd the political system and bureaucracy are.

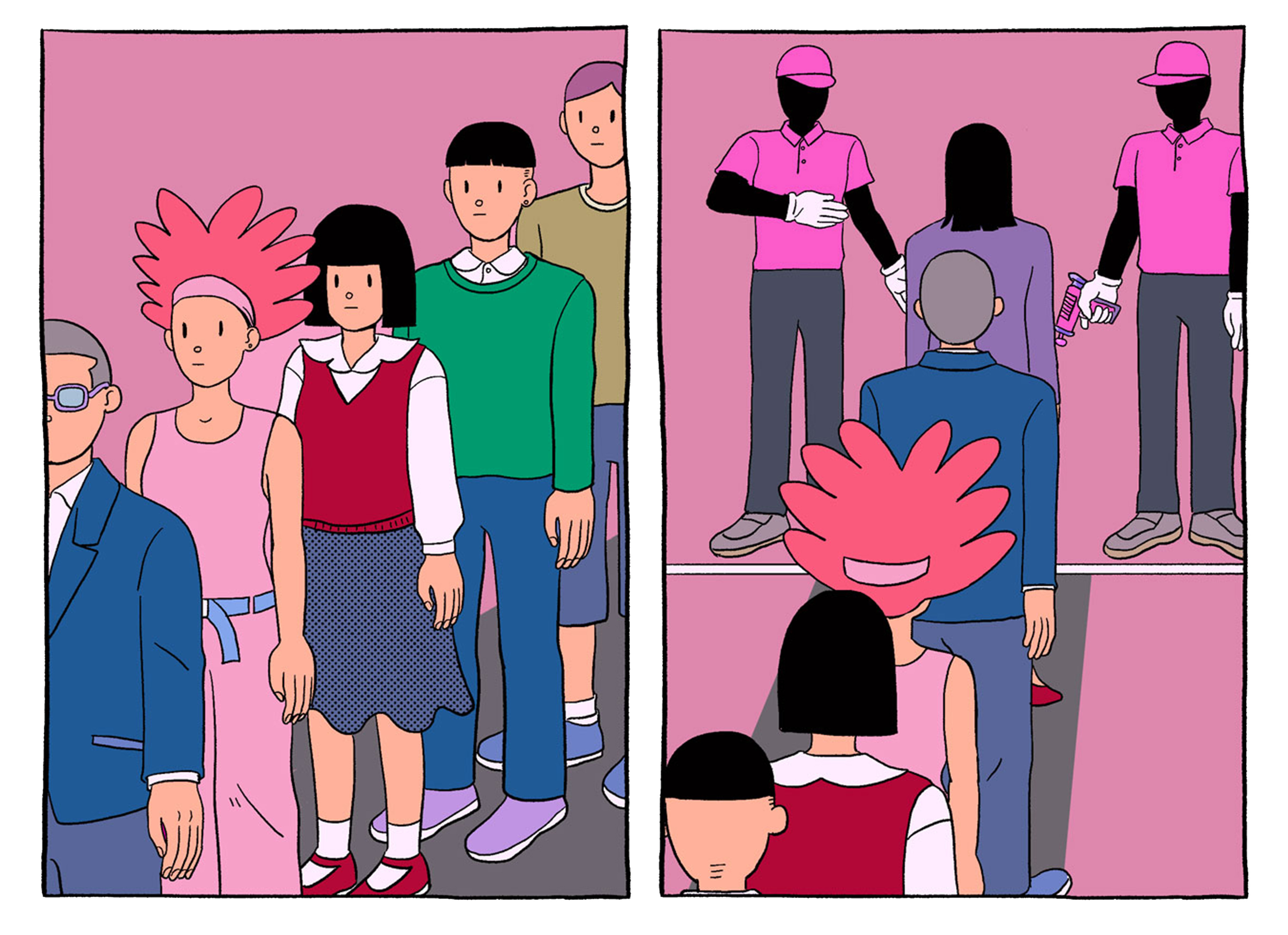

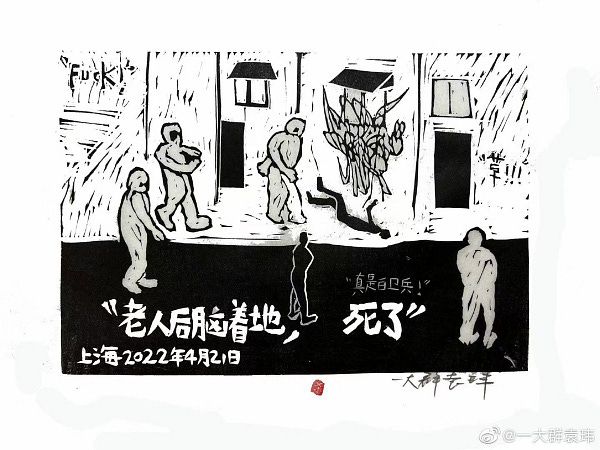

Krish: I’ve been struck by how local comic book artists have become “diarists” of sorts during this lockdown: bearing witness, capturing details, and as the web learned with the example below, helping beat algorithmic censorship.

████: On that point, while I definitely think both sides of this debate are totally valid, I’m inclined to agree with some of Lai’s supporters. Obviously there are major compromises to be made and he’s operating in a heavily restricted environment, but like Krish and Charlotte said, I still think it’s incredibly important to bear witness, and to me at least, the absurdity illustrates itself—they’re probably the best journalism to come out of the state media system since lockdown began. (Looking at you, Andy Boreham.)

Yi-Ling: At the end of the day, it’s The Old Question in a new bottle: compromise for access? Self-censorship for reach? Everyone has their own barometer to gauge integrity, safety, risk.

Voices of April | 四月之声

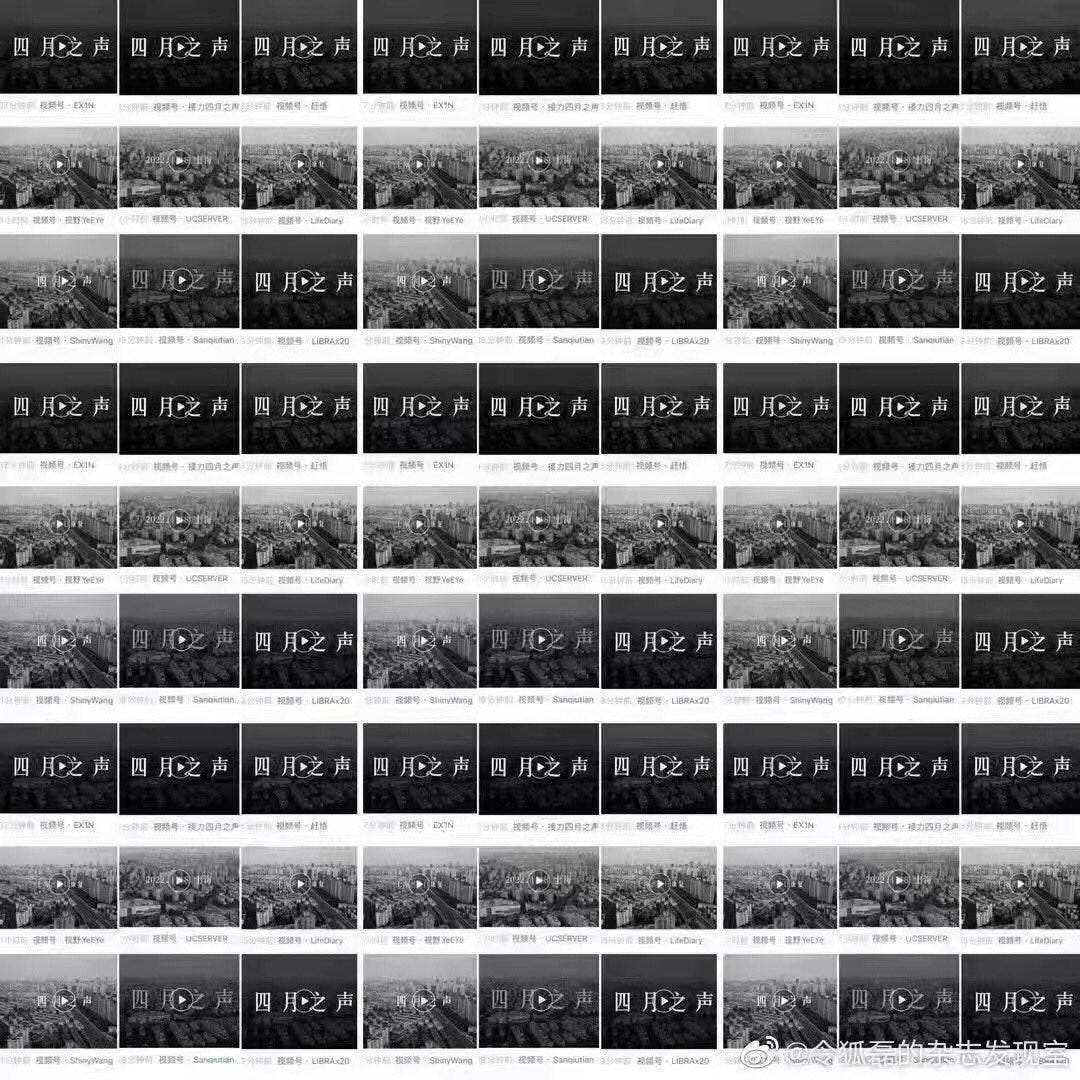

Yan: In the absence of reliable media coverage, many people, especially those outside Shanghai, learned about the bleak situation through recordings shared on social media. Some of them revealed residents desperately seeking food supplies and medical care; others showed the helplessness of exhausted neighborhood committee workers. WeChat user 永远的草莓园 made a compilation of these fragmented recordings (many of which had been censored) and amplified the effect. The video, titled “Voices of April”, offered a clear timeline of events and reflected the anger, frustration and moments of hope that people in Shanghai experienced throughout the lockdown.

It’s been arguably the most widely shared video from the Shanghai lockdown so far. When the initial video was taken down from WeChat on April 22, people resisted by sharing other versions that momentarily bypassed censorship. This was not dissimilar to the effort to keep the article “The Whistle Giver” alive in March 2020. At least 33 different versions and remixes were widely circulated before they were all taken down, one after another. Some of the remixes reversed, mirrored or blurred the original video, in an attempt to bypass automated visual-based censorship technology. Others edited in excerpts from the party’s “Core Socialist Values” or the song “Do you hear the people sing” from Les Mis to ridicule the government and show defiance. This day of run and catch was emotional for many. It was powerful to see mass mobilized resistance against censorship on WeChat, and some are already calling this “WeChat Spring.” It is not clear though, if this is just a form of slacktivism, or if it will lead to something else.

Yi-Ling: When I saw the surge of dissent on WeChat being called the “WeChat Spring,” my first feeling was sadness, my first thought: this spring will go quickly. I guess anybody who has lived and worked and has believed in online life in China will notice that the “springs” just keep getting shorter and shorter: before the WeChat spring, there was the Clubhouse spring in 2020, the Weibo spring in 2013, the BBS spring in 2003, and of course the original Beijing spring, that we know too well. The changing climate of the Chinese web. (As a side note, I do wonder whether the video-maker read/was inspired at all by T.S. Eliot, April being the cruelest month and all.)

████: While I don’t have a great answer for why this video in particular became THE one other than decent production and luck of the draw, I think Yan makes a really important point—for a lot of people, the media has become almost entirely displaced by WeChat logs and random leaks that fly around for a few hours before censors catch up. Obviously this reliance on social media happens a lot in times of crisis and social upheaval around the world, but it feels especially remarkable in the current context, where the gap between official portrayals and reality is just staggering—that’s fueling the fire as much as the actual policy issues, I think.

Henry: I wondered the same thing with the “Whistle Giver" piece—whose content is a somewhat corny, civil libertarian riff on "teaching someone to fish..." But at some point, scrolling through my WeChat moments and seeing Sindarin, Hex Code, braille, and emoji translations of that particular post, I realized that the initial urgency of content had yielded to a playfully formalist, almost Dada fuck you. What mattered was no longer decoding the message (come on, no one's going to learn the Elvish language just to read an internet rant), but the stylism and materiality of the cipher. To adapt Ennio Flaiano's phrase to these games of censorship and anti-censorship, "in China, the shortest point between two lines is an arabesque."

Tianyu: Perhaps a curious coincidence, the month of April was once associated with the anti-CNN movement in 2008, when young, tech-savvy Chinese youths protested CNN and other international news organizations for their criticism of the Chinese government in months leading up to the Beijing Olympics. The Tsinghua graduate Rao Jin founded anti-CNN.com—which at first consisted of one HTML file listing evidence of Western media “distorting facts”—in late March. Young nationalists who were involved in the movement called themselves “April Youths” (四月青年), and Rao’s website eventually transformed into April Media (四月网), a current affairs news portal. While the rebranded April Media wasn’t much of a success, the legacy of the April Youths lived on. Today, Rao is behind the social media accounts of China’s most vocal nationalist pundits like Li Yi (李毅) and Jin Canrong (金灿荣). Their followers, too, retain fond memories of the moment when young Chinese nationalists “stood up” to the West.

The voice of some Aprils ago: “2008 China Stand-Up!” first published on Sina on April 15, 2008 by Tang Jie, then a Fudan graduate student and later editor of April Media.

Emily: The VoA night was a sleepless one for me, as for many others I’m sure. I kept thinking how the video itself is precisely like the virus: warping and growing and evolving, spreading and infecting and engulfing, gripping and striking and persisting until it is “zero-ed” out. I’ve always been a pessimist when it comes to contemporary Chinese dissent but I do get the feeling that this time is going to be different. Voices of April, or “lirpA fo secioV” as some netizens call it to avoid censorship, is a complete inversion of government-constructed reality. It’s flipping the banquet table over to reveal the faceless bodies underneath, all choking on a PCR swab and moldy braised duck. Millions in and out of Shanghai resonated with it and, more importantly, millions fear the same will dawn upon them. And fear forces out screams.

Goodbye Language / “再见语言”

Yan: One impressive performance art piece was a randomly generated PSA, by artist and filmmaker Yang Xiao. It randomly stitched together 600 frequently used bureaucratic words from government and official media and was broadcasted to the compound where the artist lives. An authoritative male news presenter’s voice reads out incoherent messages without any substantial information, but it’s hard to tell it apart from real announcements. (None of the passersby in the video seem to notice any inconsistencies in the message.) The art piece calls to mind Newspeak in George Orwell’s dystopian 1984, and questions the language used to justify the government’s totalitarian and rigid measures—an accurate reflection of many people’s feelings about the situation in Shanghai now.

Henry: Not to be a broken record, but I feel like the gut punch delivered by the piece is the belated realization (or maybe I'm just dumb) that the messages are incoherent; what I'm reminded of, rather than Orwellian doublespeak (whose grammar resembles Opposite Day more than the random word generation here), is Xu Bing's Book from the Sky, another artwork which draws power from viewers' trust in the authority of appearances (this is not necessarily an endorsement of Xu—you hardly see him making a fuss about the violence of lockdown); as before with script before, so now with sound.

Emily: Parallel with the bureaucracy’s complete annihilation of the meanings behind words, COVID and COVID-related censorship is forcing Chinese folks to dehumanize as they speak. People are hollowed out and taxidermized. In everyday conversations nowadays, community volunteers, medical staff and policemen blend into one as “the Big White” (大白, referring to authorities wearing white COVID coverall suits). COVID positive patients are “sheep” because the Chinese word for “positive” is a homophone with the word for “sheep”, e.g. “a sheep was taken away today from my building.” Female positive patients are “ewes”. Apartment blocks or compounds with positive patients are “herds”. Of course many warn against this kind of discourse. This is also why, I think, Voices of April gained so much momentum as it did, because it counteracts this emergent and extremely disturbing trend of dehumanization with real voices from real people.

Siyuan Zhuji’s Nucleic Acid Test

Yan: Nanjing-based performance artist Siyuan Zhuji put a micro-camera in his mouth and documented 24 PCR tests he took in the span of about two months this year. The assembled video collage captures the sensations of going through mass testing and repetitive tests, a ubiquitous and essential preventative approach against COVID outbreaks in China. In the video frames, we see the artist taking off his mask, opening his mouth and letting a doctor take samples with a swab. The unusual perspective transforms the experience of taking a seemingly banal PCR test into surreal body horror.

Shanghai 2022 Belated Spring (上海晚春)

Emily: Another video circulating alongside Voices of April on the same night was this montage of various clips uploaded by Shanghainese documenting the lockdown, accompanied by the track “Cheer Up London” by UK band Slaves. It pieces together footage of Big White violence, stockpiling madness and balcony music performances of locked down residents as means of keeping sane. The content of the video is truly indescribable-in-a-Samuel-Beckett-way, not to mention the lyrics of the song that go “Cheer up London (Shanghai), you’re already dead so it’s not that bad.” The comments section under this song on NetEase Music were flooded with references to this video. People were vehemently mourning, relentlessly venting, scathingly satirizing and above all, engraving this spring in their memories because, I quote, “memory is the one thing they can’t erase.” I would show you those powerful words if they weren’t all taken down at 2am for “violating relevant laws and regulations.”

Simon: Typing this from inside Chaoyang, my emotions are an unquantifiable mixture of shock, sadness, sympathy, and anxiety. It’s maybe hard to extract the nuance of how—although there is a risk of overstating the differences between Shanghai and the rest of China—the city is precisely the place where you would expect life to continue somewhat normally as the rest of the country went into rolling lockdowns. It’s impossible to predict how things will go in Beijing, but I find myself hoping for a more positive outcome (either cases illogically going down, or a lockdown with better logistics) while also worrying that such a result will be used to browbeat Shanghai, as if the city brought this situation upon itself through its relative level of openness and the comparative strength of its civil society.

Epilogue: Saved by the Bell (Pepper)

Krish: One tiny source of joy for me in the midst of all this has been the Instagram account @shanghaihotel1927, a “quarantine fine dining popup” that takes the ubiquitous boxed meals delivered to quarantine hotels and converts them into gourmet dishes, using only basic tableware and material provided in the room.

Some of the transformations are just incredible, and it’s no surprise that the person behind it, Camden Hauge, is a seasoned (sorry) Shanghai restaurateur. I caught up with her to learn a bit more about the “project.” Hi Camden!

Camden: Hi! So I’d gone home to visit family + friends during CNY this year and I knew that the return quarantine would be rough so I started gathering tips from previous quarantine survivors about what snacks, tricks, etc they recommend to make 2 weeks of 套餐 food palatable. Someone had mentioned to bring your own serviceware to make mealtimes seem less soulless and the kernel of the idea was planted then—how could I re-plate this very average-looking food to make it look more edible, or perhaps even silly-fancy? (I am also incapable of downtime. I needed a project).

The sum total of my “tools” are: 1 bowl + 3 plates from Target (Kids picnic range – one is now a cutting board), 1x $3.50 knife (also from Target), 1x Thermos foldable spoon (came inside my Thermos mug), plastic fork from the airplane meal, and tweezers from my dopp kit. In terms of garnishes, both for this ‘project’ but also as a general top tip for those entering quarantine, go for simple sauces + seasoning powders (smaller, lighter for packing), plus grab handfuls of condiment packs from the airport deli before you fly. I’m not using any ingenious techniques (a sliced plastic cup as a ring mold was a high point) but just trying to think smartly about all of the component pieces and how I can put them back together in a less obvious way.

I think every sane person in F&B is simultaneously aware of the silly pretentions we tend to slip into and loves being a part of the world because of them. The dish descriptions are a nod to the ridiculous ways we have fallen into writing menus—usually either stark minimalism like “component, component, component” (what the hell will this look like when it hits the table?!) or painfully retro like “Chez Hotel Nonsense a la King”. The ‘ambiance’ captions are little jabs at the other self-referential restaurant traps we fall into e.g. collaborations with artisans on serviceware that cracks when washed the first time or niche art that no diner will notice. Some of that humor was so dry I think some followers didn’t really get it…

Krish: Do you have a favourite “rework” that you’ve done so far?

Camden: In terms of sheer deliciousness (not all are…), the pulled BBQ pork bun (pictured at the beginning) was likely a highlight. I was getting the same components for most mealtimes (breakfast = 包子 + egg + pickle + yogurt / porridge; lunch + dinner = 2x proteins + 2x veggies), and so I realized I needed to mix it up a bit, so one morning I saved my breakfast 包子 and pickles until lunchtime and was lucky enough to get 红烧肉 in the lunch set.

I immediately saw I could cut open the bao to make a ‘sandwich’ format and then the pork reminded me of American southern-style BBQ so I leaned into that flavor profile—I pulled the pork and then added some braised cabbage, carrots (picked out from a sautéed potato dish), and then added the green bean pickle on top; I threw the potatoes on the side like home fries and added some chili seasoning.

Krish: The Shanghai Hotel 1927 is now in residence at the…*checks notes* Campanile Hotel 325. Follow them here. Thank you so much, Camden!

Yan: I decided on this week’s outro music before we even started working on this issue. Shanghai-based Beijing rapper 小老虎 J-Fever dropped some verses on April 9, during the 2nd week of lockdown. More freestyle poetry than rap, it is at the same time imaginative (“work laptops are closed like pearl clams”) and political (references to the dead corgi and the separation of parents and babies). Check out his Weibo post to read some comments applauding J-Fever for being the only rapper in Shanghai “keeping it real” during the lockdown.

Krish: That’s it for this episode. Stay safe out there.

You can download and read Lisha Jiang’s comic 日常 here:

Bios

Beimeng Fu made a wild bet that her housewarming party could happen by April 15, which she naively invited ████ and other friends to. She says gutting a whole chicken without blinking in the lockdown is her coming of age.

Ye Charlotte Ming is in Berlin and suspects she has COVID for the nth time. Still negative though.

Yan Cong is based in Amsterdam. Her city has given up on contact tracing.

Camden Hauge is the owner + operator behind Happy Place Hospitality Group, as well as the co-founder and creative director of SOCIAL SUPPLY, a food-focused experiences agency.

Tianyu Fang is looking for a summer sublet in San Francisco or Oakland. Please write to tianyu AT chaoya.ng if interested.

████ is a ███████ and ██████████ at ███████ in Shanghai , and he’s pretty fucking tired of not being able to buy food normally.

Krish is tired.

Simon has been stocking up on Portuguese canned fish in honor of April 25th.

Yi-Ling is a writer who was based in Chaoyang but 润’d from Chaoyang.

Emily’s current ringtone is “Cheer Up London”, and it makes her jump every time a call comes in because the bass is too lit.

Henry wonders when he’ll be able to visit Chaoyang again.

Xuandi Wang is a writer who grew up in Zhejiang. His spiritual animal is Sufjan Stevens.

I'm in Kunshan. I've been following what I can and it's been surreal, to say the least, trying to understand the news and videos coming out of Shanghai when things here have been functional, if not good. Thanks for compiling and sharing this.