S01 Episode 9: We Built This City on a Camera Roll

The Season Finale roundtable: what is “wanghong” urbanism + the logic of internet fame + punch-in to punch-down

In the house this week: Asa, Amy, Carwyn, FATFISHBOY, Krish, Tianyu, Jaime, Yan, Yi-Ling, Simon, Henry, and Xuandi.

Krish: Welcome to our season finale.

The word “wanghong” (网红) is inescapable in China. It’s everywhere as a descriptor, online and offline. There is no precise translation. At the simplest level, it means “internet famous,” referring in its earliest iterations to viral personalities or social media influencers. The word has since mutated, expanding and venn-diagramming with a particular hipster aesthetic, strands of urban design and kinds of tech platform architecture. It can refer to people, places, cities, entire counties. Reliance on wanghong status can drive local economies, even a large coastal archipelago of villages, beaches and hills.

Depending on who’s using it, wanghong can be an aspiration, a warning (“you’ll have to queue at that bar, it’s wanghong”), or a judgement (“this art show’s vibe is a bit wanghong”). In almost all contexts, though, it suggests a certain shallowness. A hollow facade.

Tianyu: The most wanghong architecture I can think of is the Binhai New Area Library in Tianjin, first opened in 2017. With bookshelves on the ceiling shaped like an eye, the library is wanghong in every aspect: the spot is popular among social media influencers because of its interior design. If you look at the pictures, you’d wonder how readers are able to get the books so high up on the shelves—but don’t worry, the books are fake anyway. It was never designed to be a space where one reads, but rather where one poses for photos.

Krish: Here’s another, personal, example: I work for a wanghong brewpub in Beijing. It “became” wanghong in October 2020 due to this backdrop, first shot by a wanghong, an influencer, on Xiaohongshu. Here it is poorly reproduced by me, in a faux-wanghong style:

This table at our bar always has a queue. Everyone wants to “check in” (打卡) at this spot. Endless variations of this shot are uploaded hourly on every social media platform. It’s been the setting for elaborate short videos on Douyin, magazine fashion shoots with stylists and light rigs, and at least one wedding proposal. All because it’s “wanghong.”

We’ve used wanghong in the last few paragraphs to refer to a brand, a place, a building, an architecture, an aesthetic, a person, a phenomenon, and a process. Like a recent piece on the word “influencer,” in this issue we try to answer the writer Sara Ahmed’s call to “follow language around to see what it can and does do.”

Here’s why this is important. Wanghong is a concrete product of a specific tech-enabled historic moment in China. What we need is a theory for it. What does wanghong obscure, and what does it reveal? Can we ask who wanghong serves? What does itdo to our online lives, our neighborhoods, and even our entire city?

TL;DR: wanghong wanghong wanghong...wanghong?

Staring into the wanghong abyss for us are Drs. Amy, Asa, and Carwyn, three academics based at the University of Manchester (Amy, Carwyn) and the University of Leeds (Asa) who hosted a panel in May on wanghong culture, the aesthetics of Chinese cities, and the possible futures of wanghong urbanism.

Wanghong Vibe Check

By Amy Zhang, Asa Roast, and Carwyn Morris

Asa: My entry point to wanghong came from doing fieldwork in Chongqing between 2015 and 2017, and witnessing how certain sites in the city that I passed through gradually took on new significance as the background to a thousand selfies and short videos: most infamously, the Liziba subway station, where a light rail line passes through the side of a residential block. I didn’t realise it, but I was witnessing the start of a wanghong takeover of urban spaces.

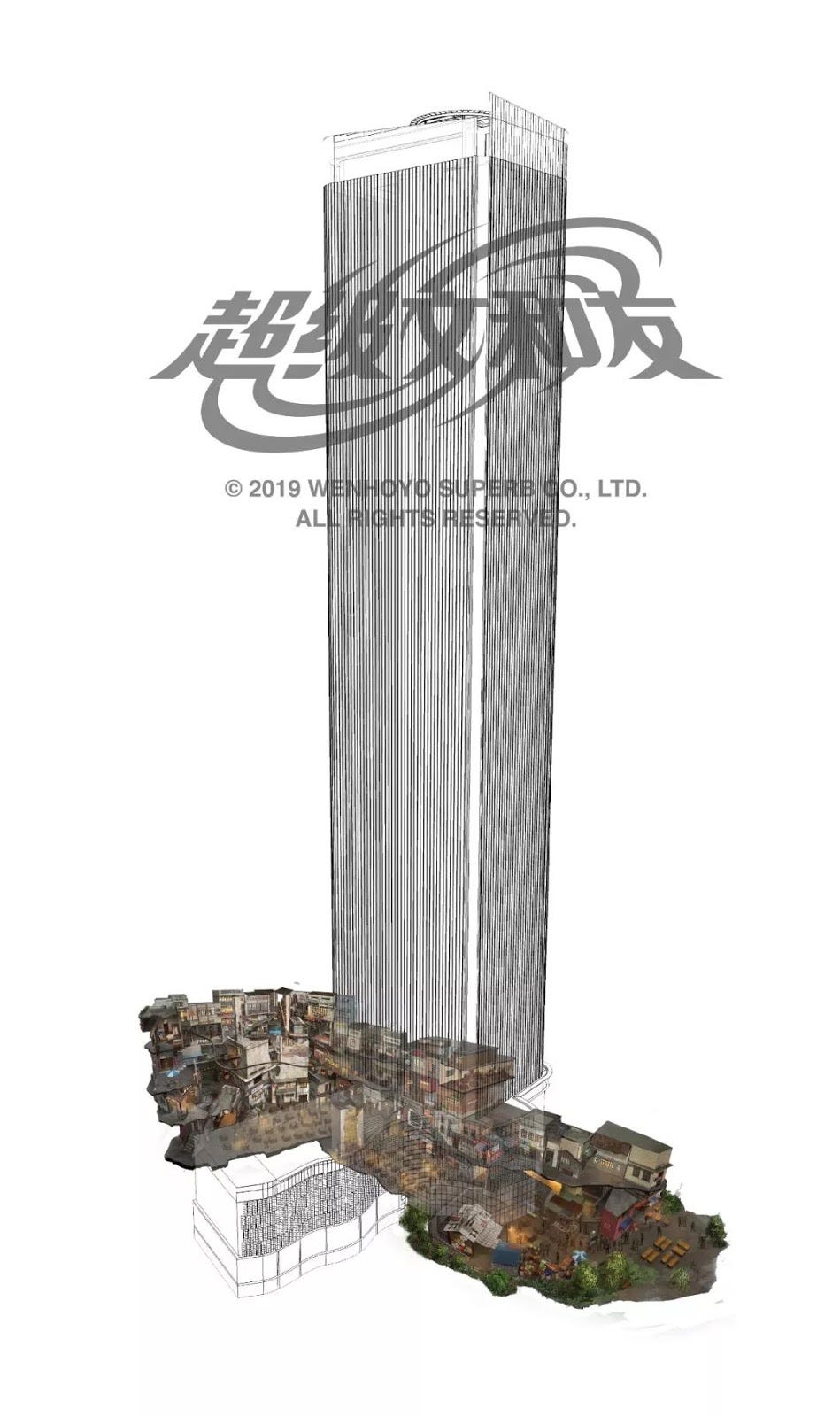

Carwyn: Lockdown boredom in 2020 took me to Zhihu posts about Changsha, and I kept seeing Changsha being described as a wanghong city (网红城市). This is the first time I remember seeing the term scaled up to an entire city and became interested in what was being described. As a serious scholar sitting in bed, I was soon obsessed with the Changsha wanghong food-experience, Wenheyou Superb (超级文和友, now just Wenheyou, with branches in Changsha, Shenzhen and Guangzhou).

Changsha Wenheyou is the recreation of a 1980s-style Changsha neighbourhood, set in Changsha’s high rise central business district and started by a young Changsha restaurateur. It's a seven-storey high nostalgia trip housing some of Changsha’s most well known food and drink spots with entry limited through a lottery system.

Amy: I started doing research on arts districts in Chinese cities 8 [😱] years ago, because I found it interesting how these places essentially function like a kind of theme park to many people. So, when wanghong attractions (网红景点) and wanghong cities started emerging, I saw them as an extension of those arts districts—may I even suggest arts districts were predecessors of wanghong attractions before this term came to existence?—but on a much larger scale.

What is wanghong urbanism?

Asa: For me as an urban geographer, the interesting thing here is how talking about these practices as a form of “urbanism” means thinking about how they intervene in the politics of daily life, place and space which make up the urban. I think Amy can explain this better than me…

Amy: Obviously, sharing photos of and experiences of visiting particular places online is not a new thing (I’m thinking of Douban, Mafengwo, and even the old Xiaonei/Renren and BBS), and it has helped make some places popular. But, the rise of app-based sharing platforms greatly increases the speed and scale of the circulation of these images and texts. In a way, the replacement of words that were used for describing certain places as being popular (for example, remen, 热门) with the term wanghong is an indication that we are now seeing a qualitatively (and quantitatively) different kind of intersection between online platforms and urban spaces.

Carwyn: One of the most interesting things is the move from wangluo hongren (网络红人, internet celebrities) to wanghong. Search analytics data suggests that wanghong gained dominance in 2015, meaning that non-humans accounts or figures could become celebrities, opening up new possibilities and forms of celebrity and celebrity interaction. Perhaps there is an ease of access to wanghong places that is not possible with human celebrities, and then one can filter that out to one’s own networks to become a bit more hong in one’s own social circles.

Asa: “Checking in” (daka, 打卡) is pre-existing terminology that takes on new significance in the wanghong city context.

Amy: The production and consumption of wanghong places seem to be very much about the imageries, whereas the experiences of these places are often secondary and are not necessarily the focus when people share about these places online.

Carwyn: Yes, my friend has been to Wenheyou in Shenzhen several times and, due to the lottery system, failed to get in. Nevertheless, she has taken pictures of the visits; daka-ing and showing off.

Shot:

Chasers:

Jaime: Wanghong now has way less to do with experience than “aesthetic proof,” to the point where buildings or restaurants or infrastructures are now being built and marketed for the sake of wanghong-ness, at the expense of prioritizing public or social functions or purposes. These are not spaces that facilitate interactions between their users, counter to what we usually think of urban social dynamics, but rather as more like a monologue between the users and the space. How did wanghong architectural design come to be valued this way?

Tianyu: In bringing oneself into the interactions between the user and the space, as Jaime noted, what role does the individual play? The OG wanghong—the internet celebrity on Xiaohongshu, Weibo, or Instagram—seems to imagine themselves as the visual protagonist of said location, as their presence and media influence make the space trendy or avant-garde. Do others who visit locations for their wanghong-ness, however, imagine themselves to be in that same social influencer position? We might think that those who patronize wanghong restaurants aspire to be wanghong themselves, but anecdotally I don’t think that’s the case.

Yi-Ling: I am going to make a big leap here: if fandoms are a form of worship, wanghong celebrities deities reincarnated in contemporary form, aren’t wanghong locations, in some ways, temples to pay homage to? The God of tech-driven capitalism—in this case, the Dianping/Meituan algorithm—has deemed this particular glitzy bookstore significant, meaningful, worthy of your attention, and so, you must go and pay homage. Because chances are, if you are a young Chinese person living in a city, you don’t have shrines, anymore, to imbue meaning on. All you have is a wanghong restaurant. And I guess, if you still remember the revolutionary days, Yan’an.

Henry: To add to all three points: if loving wanghong is worship, then it seems to be a form of idolatry—the images of these places and people are much more powerful than the real McCoy (or 真佛); architecturally, I’m reminding of Don Delillo’s “world’s most photographed barn,” whose physical existence is dwarfed by its digital presence. Human-wise, I think of the “wanghong face,” an almost baroque set of features (straight nose bridge, Disney-princess eyes, sharp, conical chin) achievable only through plastic surgery, and which seems to be made-for-camera. In this sense, I wonder if the OG wanghong don’t gain their power by becoming secondary to their online representations.

Krish: We’ve gone this far, so:

If wanghong is an idolatrous religion, can we expect an imminent rise in iconoclasts?

What is wanghong aesthetics?

Amy: One of the things that first interests me about this phenomenon is: Why this particular aesthetic??? [Cue wanghong city starter pack] What does this tell us in terms of young urban professionals’ “deep desire”?? (lol)

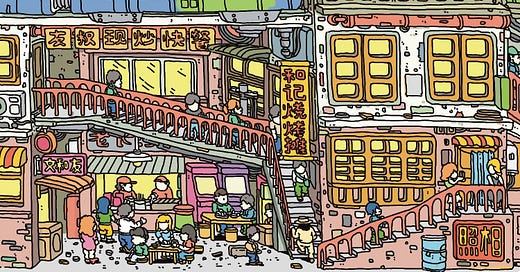

Carwyn: Looking at premier wanghong site, Changsha Wenheyou, we can see a mixture of desires. I mentioned that Wenheyou is built around 1980s nostalgia, and one of the central Changsha born co-creators is a collector of objects discarded during the demolition of Changsha’s old neighborhoods. Coupled with these aesthetics, the experience of being in Wenheyou suggests turning back the clocks, including modes of eating and group socialising more associated with pre-highrise urban China, or at least, an urban China where food culture is more organic and not policed into the ground by urban law enforcement and erased through demolition and eviction. Wenheyou looks unlicensed, it gives the sense of a street stall, it may even feel like one is eating on a street corner, but it is actually a controlled, scripted, and formalized environment.

Jaime: A real street cart food experience would include chengguan showing up to disperse the show at any moment.

Krish: An “Escape (the chengguan) Room.”

Carwyn: A place like Wenheyou only becomes possible because of the demolition and erasure of the places it mimics and sanitizes. If small restaurants and food stalls could function in a regulated, not revanchist, system, then Wenheyou would not need to exist. That is a lot of ifs and butts, and the reality is that Wenheyou does exist, and it stands in stark contrast to central Changsha’s other buildings, including the Changsha IFS Tower, China’s ninth largest building and only a ten-minute walk away.

The landscape around Wenheyou is that of high-rise urban modernity, built through top-down urban planning. This urbanism represents demolition, homogenization of the urban experience, the triumph of verticality, and the end of locality. This story is common throughout China’s large urban centres, it has taken place over the past 30-years and is still ongoing. Importantly for this discussion, this urbanism is repetitive, it does not create the eye catching difference that wanghong seeks. That is not to say this way of creating an urban fabric or being urban is bad, but its ubiquity creates blandness, and within homogenous landscapes created through top-down urban planning, sites of alterity may become fetishized.

While Wenheyou is commodifying some slowly disappearing forms of urban life, its popularity in Changsha, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and across numerous digital sites makes a clear statement: “MANY OF US STILL LIKE THIS WAY OF BEING URBAN!” In my opinion, wanghong-ness is not necessarily about nostalgia—although in this case, nostalgia plays an important role—rather, wanghong urbanism is about highlighting other ways of being. It is about multiplicity. When everything looks like a bigger or smaller version of the IFS Tower, and everyone must act in the same way regardless of which version of that tower they are in, then places like Wenheyou become sites of consumerist-alterity that highlight some of what is missing from people’s daily urban lives.

I might be pushing this too far, and this definitely isn’t the case for every urban resident, but wanghong urbanism might enable (or capture, in the camera lens) a slight democratisation of urban space and lifestyle. This democratisation has been relatively absent in the top-down “government x real estate company” vision of urban China that has dominated during Reform and Opening Up, and despite the many problems that might arise I see this as beneficial and refreshing.

Simon: The idea of wanghong-ism representing a slight democratization of urban space is an interesting one, but isn’t this often imitative behavior within different tiers of wanghong-dom? The true influencers, with corporate or tech support, help define standard behaviors and tropes, and then people with fewer followers aspirationally copy them. In a different context, there’s the example of Hong Kong’s Choi Hung Estate, where public housing became an Instagram influencer spot—a vestige of welfare state “democratization” mutating into something pretty strange. Perhaps a wanghong-led approach to gentrification crowdsources the initial impetus towards urban transformation, which is then pounced on by brands and government. As a proto-wanghong site, 798’s transformation began through ground-level actions by artists (then lacking the social or financial capital they now possess). But today the district’s state-run enterprise landlords, Seven Star Group, are happy to run the show.

It’s also worth noting that not every city, or wanghong site, is created equal. I remember taking a trip to Chaozhou and Shantou last year, and noticing that there were already signs of wanghong culture—third wave-ish cafes, restaurants with a certain aesthetic, Airbnbs—in these cities, coastal but not the most prosperous. But a few weeks later I was in Shanghai for work, and found myself thinking, while young people in Chaozhou were probably pretty excited that this stuff was available in their hometown, they would be over the moon to be in Shanghai, with its rows and rows of cafes and better preserved Republican-era architecture, already narrativized by the popular influencers based there.

Krish: Speaking of multiplicities, may I present the Hebei Academy of Fine Arts,featuring a spectacular wanghong architecture graft of Disney / Hogwarts / Neuschwanstein faux-baroque rococo. This was deliberate, a ploy to attract people to come and take photos at the university and raise its profile online:

Tianyu: I’ve recently visited Changsha’s Wanjiali International Mall, which, despite its notoriety on some parts of social media for its unbearable aesthetics, is often characterized as a wanghong mall on Dianping and other platforms. The complex, up until the 8th floor, is your typical Chinese mall, but above that there’s a wax museum, a pseudo-imperial garden featuring (pixelated) murals of pretty women and effigies of Mao and the Buddha, a giant exhibition hall introducing Xi Jinping, famous people from Hunan, and the biography of Huang Zhiming, founder of Wanjiali. At the top of the mall are eight helipads, and though it’s unclear if any helicopter has ever landed there, it’s a pretty popular wanghong “check-in” spot:

The post-socialist, nationalist, nouveau riche aesthetics of Wanjiali may be at odds with what one typically thinks of wanghong spaces. First, Wanjiali caricatures the fictitiousness of wanghong places—evident from the fake imperial garden, the useless helipads, and the imaginary official-ness the Xi exhibitions embody. The pictures of it look great, but a closer look reveals its counterfeit nature. This doesn’t undermine the fact that most of Wanjiali remains a community mall, with milk tea shops and Haidilaos, but it’s the fictitious aspects that are amplified by online influencers. Second, the wanghong aesthetics aren’t singular. The term’s versatility (there’s a wanghong narrative to almost anything) belies the fact that different strata of China’s urban society could have different answers to what wanghong is: a patron of Shanghai’s wanghong Bulgari Hotel may not be impressed by this fake Greek sculpture at Wanjiali’s outdoors garden at all.

Asa: One thing I would say is that this idea of a different way of being urban or a different form of modernity is very much in the eye of the beholder, and if that is the gaze of a first-tier urbanite imagining a more meaningful version of urban life in Changsha or Chengdu that it is just that: imagined, and based on interpreting at these places as “other” to the cosmopolitan modernity of the first tier cities of Beijing-Shanghai-Guangzhou.

I would see this as easily feeding into a kind of shallow fetishization of authenticity and an aestheticized vision of old-fashioned urban ambience (市井气息) which remains largely ignorant of the local economies and cultures which become wanghong-ized. In this respect, it reminds me of the fetishization of a certain aestheticized vision of city life in discussions of “new urbanism,” “creative cities,” and ultimately gentrification in Europe and North America—which is not to say that wanghong is the same as gentrification! But there is a clear parallel with the kind of conspicuous consumption of nostalgic and notionally “authentic” built environments which Richard Ocejo describes in his ethnography of craft labour in Brooklyn.

Amy: Right, and this kind of aestheticization of the “run-down” or fetishization of “authenticity” is also not new in Chinese cities. I’m thinking of my previous research on arts districts based in (post-) industrial spaces. The popularity of these places partly comes from an aestheticization of industrial decay and the urban past, which depoliticizes the meanings of those preserved traces and fragments of a generally lost urban past.

I would argue that the appreciation of an alternative urban aesthetic is not entirely done by urbanites from tier 1 cities, but it is more a reflection of the concerns of certain stratas of the society, not necessarily those who are more socio-economically disadvantaged. The fact that Changsha’s Wenheyou was shortlisted for the “City for Humanity Awards” organized by Sanlian Weekly this year, which intends to promote more “human-centered” city-making, demonstrates the limitations of such appreciation.

Carwyn: If wanghong sites can someday influence the production of a more human-centred city, one that the interlocutors from my previous research project (migrant food stall and restaurant owners) are not violently erased from, then I don’t want to be completely cynical. The caveat being, as we’ll discuss more later, only certain cities are wanghong cities, and it is mostly provincial capitals that carry this label right now.

How is wanghong reproduced?

Jaime: If we take away the digital aspects of wanghong-ness, what about wanghong’s similarities to traditional tourism? Why and how wanghong proliferated from leisure spaces, especially considering the tremendous amount of labor to contribute to and reproduce in the wanghong economy—the styling, the shoots, the equipment, the time spent on the whole photo enterprise…)

Tianyu: Daka is the V-pose of Chinese Gen Z.

Jaime: And who is the Balzac of Chinese Gen Z? A recent article on chibo (吃播) and food waste by Lina Qu makes a good point about how China’s new Gilded Age is related to this grotesque display of affluence—but I think not only in terms of being rich in content, but also being rich in time (that immediately gets exploited):

“The parasitic relationship [between Chinese popular culture and political propaganda] is strengthened in the era of social media by the vanishing distinction between venues for information and leisure. How the prevalence of food visuality on social media echoes the state-engineered discourse of Chinese affluence attests to this ‘parasitic relationship’.”

Amy: Now this links to the next aspect that I see in the connection between wanghong places and wanghong people: wanghong places serve as the backdrop of (some) wanghong people’s photos and become part of their brands. The influence of wanghong people as trend setters then drive a section of urban consumers to consume the same places and aesthetics, producing hundreds of similar photos at the same spot and from the same angle in order to demonstrate that they are keeping up with the trend, or, as Carwyn mentioned, to “become a bit more hong” in their respective social circles.

What’s especially interesting to me here is a necessity for the sameness of the “outputs” coming out of the consumption of wanghong places, which goes beyond the typical experience of photographing and documenting a visit. For example, when reading a guide for visiting Changsha as a wanghong city, I noticed the guide repeatedly mentions how to find the exact angle to take the “classic” photos that are associated with Changsha’s wanghong-ness. While any images shared online of a city are always fragments of the city, wanghong consumption leads to an even more reductionist representation of the city. The attention and labor goes into reproducing the uniform wanghong “outputs” also raises more questions about the potential and limitations of appreciating an urban alternative on aesthetic basis.

Xuandi: What Guy Debord said decades ago has become more relevant than ever:

“In societies...all of life announces itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.”

It is haunting when I imagine how people might travel and navigate an unfamiliar place through revisiting and recreating what they’ve seen online—there is almost some dictatorial power to wanghong-ness—constraining your mobility and stripping away all the potential serendipities from randomly strolling around a place.

Carwyn: One question people might be thinking: is this not Instagramification? Although simultaneous phenomena, the geographies of wanghong fame differ from those of Instagram fame. Crystal Abidin’s work has explored in detail internet celebrity as an industry and phenomena across the globe, but in Abidin’s extensive writing on fame the person is still central. When the human is decentred on Instagram, it is becoming replaced by algorithmically created artificial humans, as discussed by Alice Marwick. Certain places become famous, but that fame rarely becomes central to the narrative. For instance, the pastel wall at Sugarhouse Studios in London did not become a site through which new forms of profit could be extracted for its creators or the Greater London Authority, even though it ticked many of the aesthetic boxes. Rather, it became an image reproduced devoid of context on smartphone covers and recreated in Beijing, part of an exhibition of global wanghong walls. What differs from Instagramification is less the aesthetics, more the industry building up around these sites, the centrality of space and place in celebrity, and how space is being exploited for profit.

It is precisely this spatial element, and its relationship to politics and economics, that is interesting about wanghong urbanism in China. Not every city is a wanghong city, some cities have wanghong-places and sites of tourism, but wanghong cities are their own niche and many cities labeled this way are provincial capitals.

Amy: This is about a consumption-led production of the urban. What do I mean by this? To me, wanghong urbanism is about taking wanghong places onto a larger scale or projecting a city’s wanghong places onto the city. So for a city to be a wanghong city, it must have a presence of unique wanghong places that are strongly associated with the city and that are recognized not only locally but also nationally. Thus, wanghong-ness, in terms of a particular kind of place and aesthetic, becomes the identity and brand of the city.

Jaime: “I'm internet famous because I possess many internet famous characteristics and I display internet famous behaviors.”

Asa: This also links to Dino Ge Zhang’s work: wanghong as a logic rather than a noun.

Amy: It is the intersection between the rise of consuming wanghong places and the lack of existing, strong aesthetic identity/brand of certain cities that generates wanghong urbanism: to me, this particular kind of city branding (whether intentionally or unintentionally) and the dynamics behind it are what wanghong urbanism is about.

The reproduction of wanghong aesthetic and facade that takes place not just through individuals’ visits and replicated images but also by literally replicating a site in different cities is certainly another important aspect of wanghong urbanism. The latter demonstrates how certain cities and urbanism actually become influencers who exert influences on other places and cities over their aesthetic choices, just like those Weibo and Instagram influencers. And the fact that it is Changsha (a tier 2 city in China’s urban hierarchy based on economic development) influencing Shenzhen (a tier 1 city) not the other way around is an interesting dynamic.

Carwyn: WHITHER THE (so-called) TIER 1 CITY!

What kind of criticism is wanghong facing?

[images]

Asa: An important point to note here coming out of Amy’s discussion is that some of this is not particularly new. We have to understand the idea of a city itself being wanghong in a broader history of “city branding” and “place making” which has long been a tool for cities marketing themselves or seeking to project a certain image.

One of the interesting things in the case of wanghong cities is that these are images of the city and visions of the urbanism which are “chosen” for prominence by the users and recommendation algorithms of these apps. The application of wanghong to a place is decentralised and networked. So they are potentially a lot harder for city governments or propaganda departments to control, and not necessarily easy for businesses to exploit or benefit from, or for a place to stop being wanghong once it has become so!

There’s no single person or body which can grant or refute wanghong status—rather it (at least in theory) emerges out of lots of millions of individual shares and likes. It introduces a degree of uncertainty in the semiotics of these places and how they are visualized and used: you cannot always choose which places become wanghong and for what reasons.

Carwyn: I agree, but we must also remember that institutions, companies, governments and people will try and influence it. There are numerous wanghong influencer companies, though some within that industry are hugely dissatisfied with their jobs as wanghong. And anybody who has been to a gallery or cafe in the last ten years sees that environments are being designed for 赞-worthiness. But, to my knowledge, there isn’t the same level of wanghong industry producing wanghong places and cities… yet.

It is also very important to remember that tech companies—most of which are based in tier 1 cities—are extracting profit from this entire process, and from the activities that take place in other urban and rural places across China. If someone just “checks in” for a photograph outside of a wanghong place and then moves on, they're producing content which generates value for Tier 1 cities and makes little economic contribution to the wanghong city itself.

Amy: As the joke goes, “Hangzhou is wanghong’s city; Chongqing and Changsha are wanghong cities.”

Krish: I feel like this raises an interesting question of what the wanghong is in relation to cultural production and “scenes.” Echoing n+1’s classic panel discussion on hipsters, is the wanghong a “permanent cultural middleman” in hypermediated capitalism, selling out and co-opting alternative sources of social power developed outside tech and official hegemonies? A poisoned conduit that completes the circuit between cultural capital and the marketing machine.

Tianyu: We should consider the emergence of wanghong culture in the broader context of the conglomeration of Chinese technology behemoths in the most recent decade. As one consumes wanghong culture on Weibo, buys tickets to wanghong cities on Fliggy (飞猪), looks for recommended wanghong spots to “check in” on Amap (高德地图), and eventually pays the vendor on Alipay, tech giant Alibaba’s corporate synergy is involved throughout this process.

The wanghong “gaze”

Asa: There’s also something interesting going on with temporality here, imagining the first-tier vs rest hierarchy in terms of an inhumane present and a more human past. This temporal aspect is something which came up really regularly during my fieldwork in Chongqing. I had several conversations with people visiting from tier 1 coastal cities who would say the thing which they found most appealing about Chongqing was this sense of temporal disjunction: an urban core which looks in some ways more “futuristic” than Beijing or Shanghai, combined with a sprawling periphery that (as I was told) felt like going back in time to the 1990s. It’s a sense of juxtaposing futuristic modernity with unfinished “authentic” local culture, and I think a lot of the wanghong sites in cities in Western China play off this aesthetic. The wanghong gaze loves combined and uneven development!

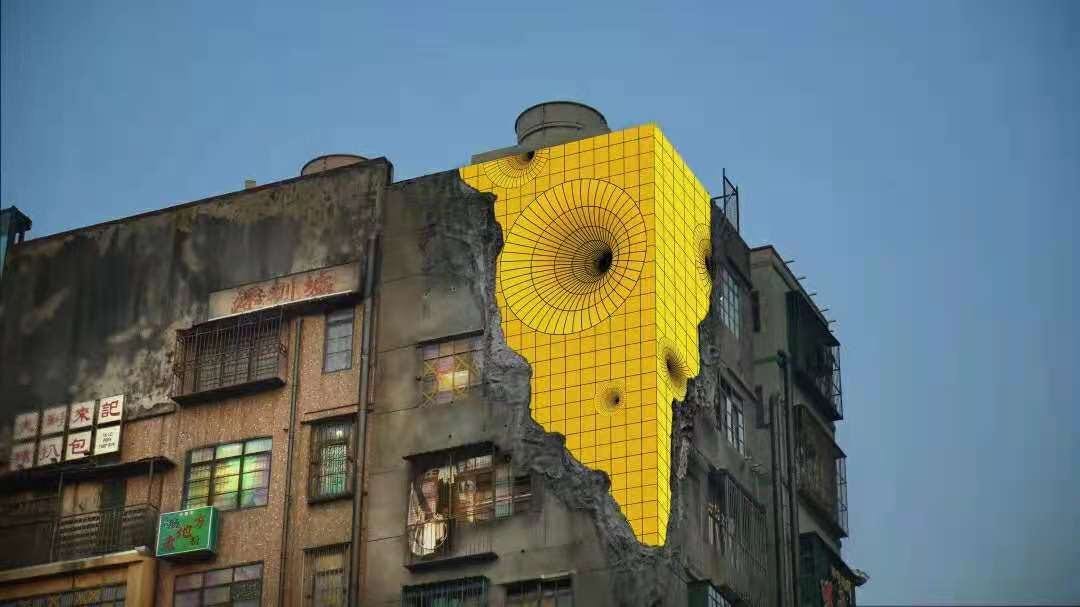

For me the most interesting point becomes how the gaze of wanghong urbanism impacts those “other” places it lands upon. Chongqing is a great example to talk about in this respect, because while it has become one of the pre-eminent wanghong cities, the places which tend to get imaged as wanghong are largely not dedicated tourist sites or commercial centres. Besides Hongyadong (basically a nostalgically-themed mall) and a few restaurants / night markets, the most wanghong places in Chongqing are very unlikely sites of consumption: a subway station, a footbridge, the edge of a highway, an old cable car from the 80s. These aren’t sites which have deliberately cultivated the wanghong image (at least initially), but they have quite accidentally found themselves the subject of wanghong attention.

The result is a kind of wanghong-ization of infrastructure. There is no better example of this than the infamous Liziba “building-piercing train” (穿楼轻轨) in Chongqing.

When I was doing fieldwork in Chongqing, I started to notice young tourists riding the train through the station and taking videos of it, or gathering on the street below to take photos of it, from around 2017. Cut to the present, and we have a new “viewing platform” constructed next to the station to cope with the volume of tourists, residents complaining about people crowding the street and knocking on their doors, and plans to regenerate the area and construct a giant LED resembling a hotpot on the side of the building so that the train appears to be plunging into it.

The problem here is that the city has different values for different people who encounter it. If a bit of urban infrastructure becomes wanghong, that can potentially disrupt the actual day-to-day function of that infrastructure and the lives and needs of local residents around it who are dependent upon it.

Carwyn: Wrapping up, I just want to tie what you said to something mentioned earlier. When people just engage in wanghong tourism, visiting the wanghong sites of so-called wanghong cities, they produce profit for tech companies and become a small bit of information in larger data economies. But, during this process, they may not always be supporting local people and businesses. We’re still early into our enquiry of the wanghong city, but, if engagement with the wanghong city means profit for Tencent or Alibaba but an unsustainable future for locals, then it is important to consider how a wanghong city reproduces and deepens existing urban inequalities.

Henry: The (Beijing) exhibition of wanghong walls that Carwyn mentioned reminds me of China’s World Park, which offers a kind of “poor-person’s backpacking trip” (or espouses a kind of “isolationist cosmopolitanism”). But in (pre-Covid) present times, plenty of Chinese hipsters are visiting the actual Berlin wall and Sugarhouse Studios, which makes me wonder: is wanghong-dom contiguous with Mainland China, or can its borders be extended overseas by such image-production?

Amy: I think the reach of Chinese tourists around the world has already extended the borders of wanghong consumption, which generates spatial effects. For example, with the steady flow of Chinese international students to UK universities, during COVID, we have seen the wanghong gaze resting on more unlikely sites. Asa and I recently took a field trip to a scenic spot in the Peak District national park, which has become an unexpected wanghong site for students to check in, prompted by popular posts about the spot on Xiaohongshu. The wanghong status has noticeably increased the number of visitors to this particular spot. However, we are yet to see whether wanghong-induced spatial production would similarly extend overseas.

Carwyn: Pumping money into the built environment in these ways requires specific economic and political conditions. But economic and urban development does not follow a linear path, other areas of the world may move in different directions, or produce different results while attempting to follow the wanghong urbanist path. At the corporate level, though, companies are obviously learning from one another. ByteDance—owner of TikTok and Douyin and a major force behind wanghong city branding—is a huge global player while Euro-American companies have a potentially unhealthy and orientalist obsession with the Chinese internet. I could definitely imagine British based companies or joint-ventures attempting to reproduce the forms of profiteering described above, whether they will succeed in reaping the profit they so desire is another question.

Tianyu: Thanks for exploring Chaoyang Trap World 1-9. If you’d like to daka for online clout, please use this button and tag @ChaoyangTrap for a repost:

This is also the end of Season 1 of Chaoyang Trap! We’re taking a few months to recharge, and we’ll be back with full fortnightly episodes towards the end of the year. We’re still going to be pretty active on the Substack. Expect a few special interviews, reflections from Season 1, shorter dispatches we’ve been working on recently, and a surprise project we can’t wait to reveal.

Krish: Outro music this week is a warm slice of dream pop from Chengdu’s Deep Water, who’ve “checked-in” with 9 other wanghong bands in China to create fuzzy, filtered recreations of familiar indie songs. Here's the album trailer, and the whole thing on Spotify and Apple Music.

Tianyu: Bye!

Amy Zhang is from Chaoyang and now works in Manchester. Her research sites have all become wanghong sites.

Asa Roast is an academic based in Leeds, missing Chongqing.

Carwyn Morris is a Manchester based academic who is yet to arrive in Manchester. He writes on dynamic stillness in Beijing.

FATFISHBOY is a Shenzhen-based illustrator who loves fountain pens.

Tianyu Fang was a Beijing transplant in New England, but he’s moving to California. His website shows up if you look up “Chaoyang Trap” on Baidu.

Krish Raghav is a comic-book artist in Beijing. He works for a wanghong craft brewery.

Jaime (bot) works in Chaoyang and has moved to Chaoyang.

Yan Cong is a Beijing-based photographer, and one of the founders of Far & Near, a Substack about visual storytelling in China. You should subscribe!

Yi-Ling Liu is a writer in Beijing. She believes deeply in the importance of spinal integrity & flexibility.

Simon Frank is a writer, editor, and musician in Beijing. His new album So Dream It is out now on Absurd TRAX.

Henry Zhang is a writer in Beijing. He believes in life after love.

Xuandi Wang is a writer who grew up in Zhejiang. His spiritual animal is Sufjan Stevens.

Most interesting read, Wanghong almost seems an informal revenue sharing, where social media platform identifies an aesthetic that gains attention (the currency of social media), then pays the attention of others in return for reproduction of that aestheic.