S02 Episode 8: Jokerfied on Literary Pornhub

Slash fiction in China post AO3: hitting the org//asm paywall + meal replacement fandom diets + Alpha-Omega-McDonald’s + cyber tomb-sweeping

In the house this week: Emily, Yan, Krish, Yi-Ling, Simon, Aaron, and Jaime.

Krish: Hello. In this episode, we’re continuing our exploration of desire on the Chinese web.

In 2020, the fanfiction site AO3 ("Archive of Our Own") was blocked in China. Long a safe haven for the country's diverse strands of erotica, fan works and danmei literature, its disappearance behind the Firewall was devastating. The furious drama surrounding the block spilled over into mainstream culture. When the dust settled, the question on everyone's mind was: what now?

Our focus here is on slash fiction, and the mind-bending ways in which fanfic writers and artists in China have adapted to the “post-AO3” era. In the shipyards of fandom below, you’ll learn about meal replacements, community-builder bots, and horny animal sounds.

Yan: Back in Season 1, Ting wrote about the fandom trend of nisu—changing the gender of your favourite idols to intensify crushing on them. In this piece, we also discover gousu (your idol is now a cute dog), maosu (your ship is now two cats frolicking), and…Pixar-su?

Krish: We’re really excited that Emily—aca-fan by day and unapologetic slash reader/writer by night—is our guide on this voyage. She shows us that ships and slash and danmei erotica aren’t marginal phenomena on the Chinese web. They’re the frontlines of how we live with algorithmic censors, bend platforms to our will, and build worlds within worlds online.

As Michel Foucault, renowned scholar of Chinese fandom, once put it: “the ship is the heterotopia par excellence. In civilizations without ships, dreams dry up.”

Soy Boy Soylent: Slash in Post-AO3 China

By Emily L

Emily: In the danmei calendar, 2022 A.D. is known as 2 P.AO3. I know that sounds like the name of Elon Musk’s third child with Grimes, but let me explain.

Early February 2020. Fans of the actor Xiao Zhan are taken aback by a piece of homoerotic fiction featuring Xiao and his male co-star in the series The Untamed (陈情令), published on the renowned fanfiction site Archive Of Our Own (AO3). It portrays Xiao as a cross-dressing, nonbinary sex worker. My beloved Alpha-Idol-God degraded to a drag-wearing prostitute? Unacceptable, they say. The retaliation starts. They collectively (and excessively) report the website as containing “pornographic” materials to China’s Cyberspace Administration Office. This is…not untrue.

On February 27th, the site joined Youtube, Google, Instagram and various other Western websites (the list goes on) in being blocked by China’s Great Firewall. “Great” in the sense that it censors the best of the best, from the Hugo Award-winning AO3 to the one who sits on the empty chair.

Thus we enter the “P.AO3” era. Of course in the wake of the ban, there was mass outrage. AO3 was one of the last remaining sites accessible to Chinese fans for reading and posting NSFW danmei male homoerotic content, and to do so alongside a global fanfic community. This “literary Pornhub”, as Ting called it, was very much idolised itself. The danmei community saw the Xiao Zhan incident as an insidious attack of their artistic freedom and their right to create. Fans from virtually every other fandom (even arch-enemies like the Otakus and the K-Poppers) rallied together to begin a universal boycott of Xiao and his supporters. People openly refused to be affiliated with them in any way, be it watching Xiao-starring entertainment programs or buying products from Xiao-endorsed brands. This series of events were coordinated under the umbrella hashtag #227Solidarity (227大团结). The spirit of #227 continues as the danmei community are still, to put it mildly, furious as fuck.

To this day, netizens digitally re-enact ancient “fire-jumping” traditions intended for warding off bad luck, posting a GIF of a fire pit every time they see Xiao’s face offline and online, casting him as a repulsive bad omen needing to be exorcised. A quick search on Weibo reveals that “fire-jumping” posts—daily, ubiquitous—are now almost exclusively associated with Xiao, all expressing intense dislike.

Krish: This has led, on the other side, Xiao fans to become so Jokerfied that they just want to watch the web burn. Indulging in the illusion that their innocent idol did nothing wrong in the lead up to 227, and safe in the knowledge that they will be forever alone and endlessly hated, their nihilism has gone into sicko mode. As a group, they've largely descended into picking random fandom fights and trolling everyone they come across.

Emily: Now in 2022, I want to sketch the landscape of slash in the post-AO3 era. How does a community rebuild after the loss of their home base? I write with the intention of chronicling this new beginning, this new reality for the Chinese danmei community and their NSFW creations.

First, where have danmei writers taken their work?

Some have explored uncharted territory, like flocking to the Chinese app “AiFaDian” (爱发电). New to the market and currently escaping the firewall radar, it brands itself as a “creator sponsored” platform that “returns freedom to creators”. Developed by a team of 5, the founder claims that it is built on the model of Patreon1 and that they do not censor homoerotic or NSFW content. The caveat: full (read: NSFW) content can often only be unlocked by readers through a donation. So it’s OnlyFans for fanfic. While AiFaDian does provide writers with the option of granting followers open access to their works without a donation, it comes with a risk, as homoerotic content can (and did) place writers in danger of serious persecution. Writing and publishing a bit of gay smut in China might leave the writer doing more time than rapists and spend a decade in jail. The OnlyFans donation-based mechanism somewhat guarantees safety for danmei writers, building a wall around evidence that could be used against them.

This AiFaDian model brings about tectonic shifts to the very meaning of artistic freedom in the fanfic community. When the sugarcoat disintegrates, the fallacy is blatant: freedom is there as long as you can afford it. You pay for your right to read freely. Likewise, your freedom to create content in safety is only guaranteed if you commercialise your work.

Jaime: Galaxy brain but the membership-as-safety-lock-against-the-state model has also created a dynamic in indie film where film clubs are branded in a way that seems "exclusive"/high entry of barrier, in order to filter people who are actually serious enough about it to go through the process of joining after which it's…just actually super casual.Yan: The interesting paradox here is that this kind of paywall protection against censors/regulations only works for online spaces, for now. On the other hand, profit-making is a liability in self-published physical zines. In the case of the persecuted slash writer mentioned above, it was exactly because she sold her work and earned some money. Similarly, a photographer was arrested for selling pornography after she self-published a photobook containing nudity last year. It feels like maybe the regulators haven’t caught up on what’s happening on AiFaDian. Or, like Jaime said, since the subscription works as a filter to let in only serious readers, the small crowd who’re willing to pay don’t make up a critical mass for regulators to care?

Emily: The opportunity to monetize your fanfic side hustle is, of course, welcomed by some writers. But this does not obscure the fact that AiFaDian is using its “champion of freedom” rhetoric as a smokescreen for its neoliberal consumerist platform logic. In fact, its founder has indicated in interviews that AiFaDian wants to encourage creators to “build their own brand”. Therefore the “paying fans / users,” will see the benefits and be “converted into creators themselves2.” This is the classic “assetization of data” model that drives all large platforms, with values like freedom of speech always secondary to those impulses.

On the other hand, many more have reluctantly decamped to Weibo. With some 200 million daily active users, it is one of the largest social networking sites in China containing a multitude of “dissonant shouting voices3.” Writers can publicize their works either as a long post (the character limit is no longer 140) or as a long vertical image containing the texts, before interacting with their readers in the comments.

Writers’ reluctance to use Weibo comes from the platform’s notoriously servile and heavy-handed approach to censorship. This makes Weibo the least ideal place to post male homoerotic content, let alone making it R-rated.

There used to be a celebrated alternative to Weibo, LOFTER, which gave writers more leeway. It's fallen out of favour after a brutal crackdown circa 2020 with government campaigns like Qinglang (清朗) that aimed to sweep the internet of “inappropriate” material. LOFTER writers were left “deleting passages until there are no words left to be censored”, as one author put it. Just last week, the few remaining LOFTER users were horrified to see how the platform is now displaying explicit ads that encourage women to sell their eggs, yet censoring all…activities between two men from their noses down. Funnily enough, the post exposing this observation is itself censored on Weibo.

Yan: In my limited experience with reading fanfic when I was in China last year, the most ridiculous platform-hopping I did in order to read slash was: I started from a Weibo post with a link which took me to a Douban post, whose comment contained a link to a fanfic written in Chinese published on a South Korean platform. As a reader, the amount of work you had to put in to keep track of slash writers’ new work on multiple platforms was insane. Plus, platform-hopping was only fun when all links worked: you were rewarded with the joy and excitement of a new work after being redirected between apps, webpages and switching VPNs on and off. It was really tiring, and I can only imagine how tiring it was for slash writers.

Emily: As a saying in Chinese goes, “pick the tallest dwarf”, referring to the necessity of “just make do,” now, everyone just has to suck it up—Weibo is mainstream enough that all slash lovers presumably have ready access. It saves readers from the hassle of, say, downloading a whole new app like AiFaDian or having to navigate around new sites using VPNs. Frustration with censorship is therefore borne with grace, and by grace I mean the invention of astoundingly creative ways to evade censorship.

Yi-Ling: “The cute cat theory, except the cute cat is gay erotica.”

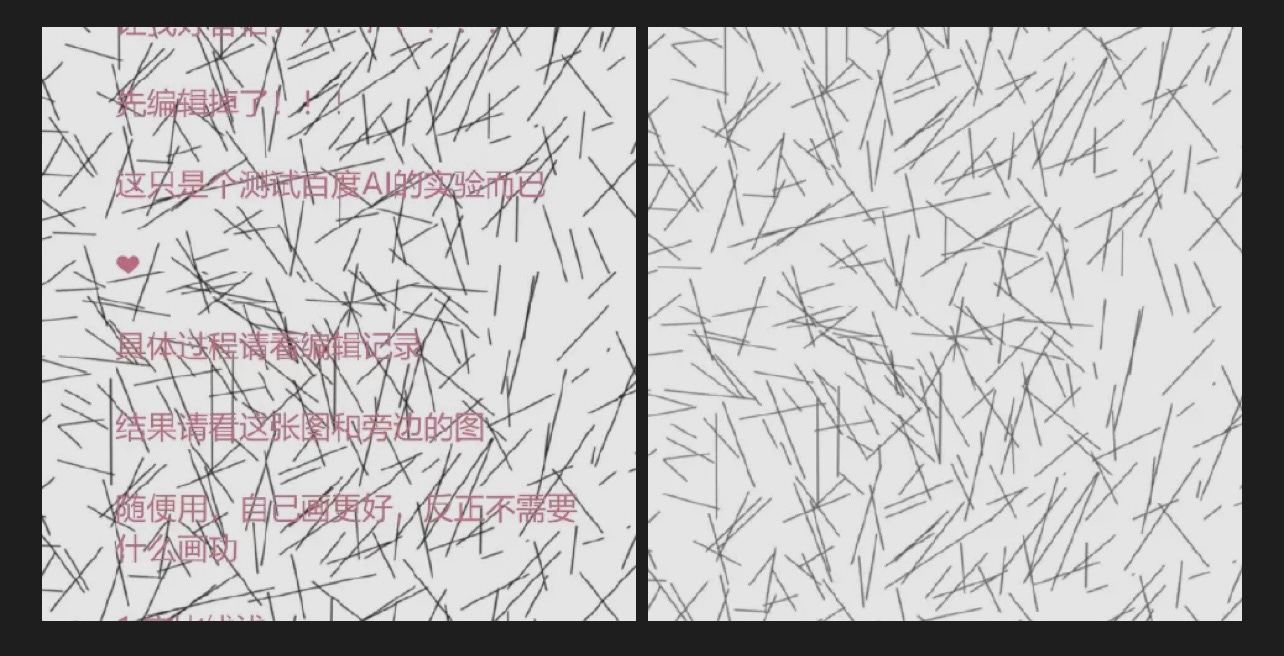

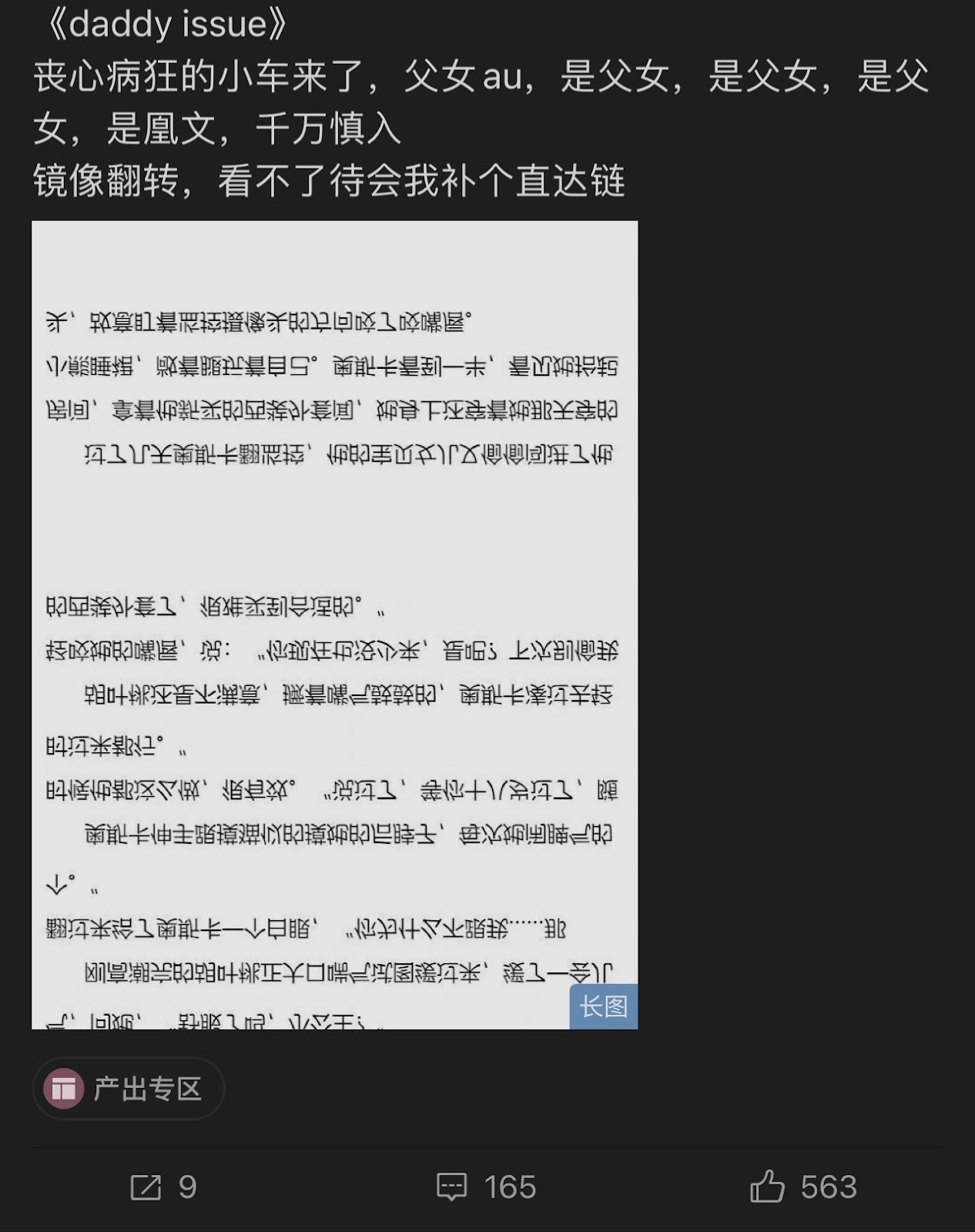

Emily: Some common evasion techniques include special characters in between words to dodge keyword filters: “org//asm”, “pen//is, “s/e/x” etc. For a longer piece in the form of a photo, doodling, blurring, flipping the photo upside down or mirroring the image horizontally can all mess with the algorithm.

Writers even go to extreme lengths, conducting rigorous experiments to test the effectiveness of different methods of evasion. In this one instance, the image on the right needs to be overlaid on top of the text for the best result (left), the writer concludes:

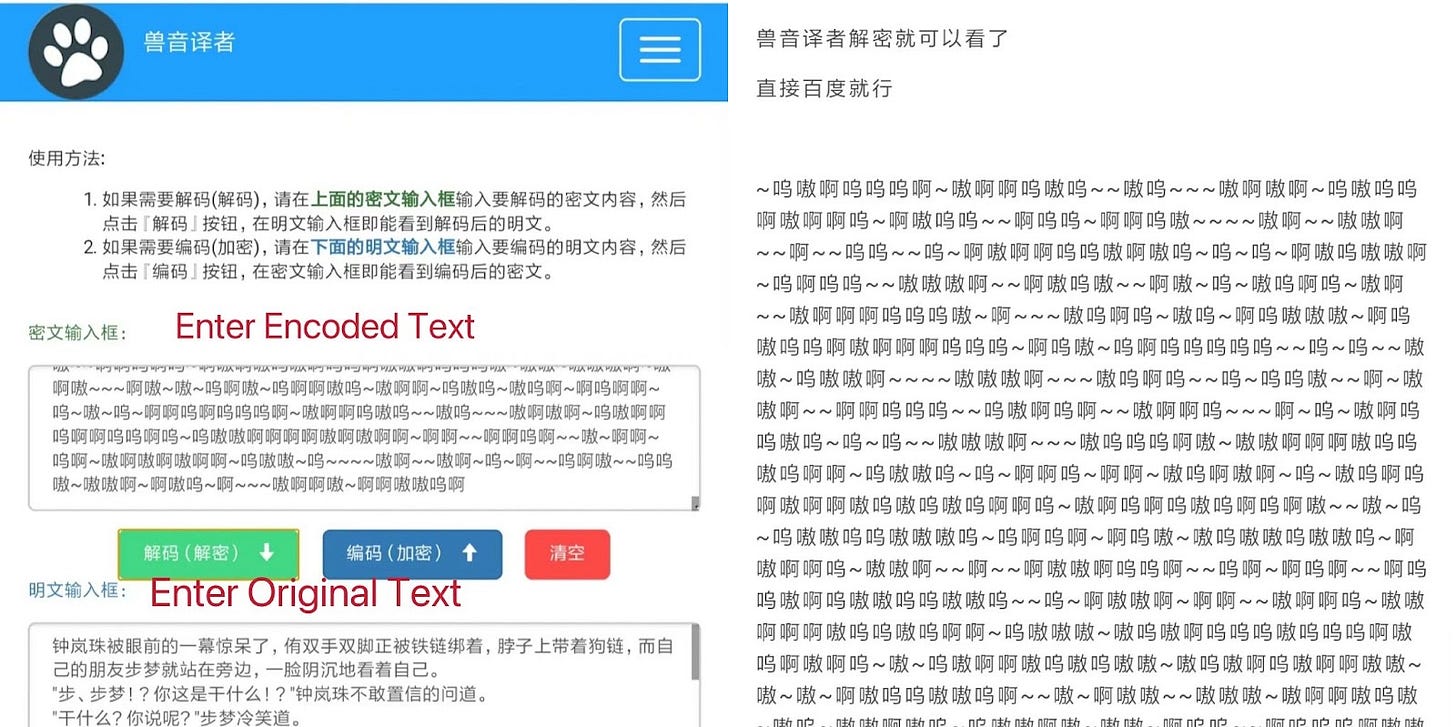

The latest development in 2 P.AO3 is the insanely innovative use of an “animal communicator site”. Writers encode their text by running it through the “translator”, basically an encryptor. The result is a series of animal sounds, WUUUs and AAAHs and AOOOOs onomatopœically representing the horniness within. The writer would post the encrypted text (right) while attaching a link to the translator in the comments section for readers to decode themselves. I mean, who says Dadaism is dead?

But what sets AiFaDian/Weibo apart from AO3 is rarely, if ever, noted. AO3 is a discussion forum that revolves around literary creations as the centrepiece. It’s in the name too: the “archive” of AO3 creates rabbit holes, connections, lineages. Its emphasis is on how fanworks speak to each other in a fandom or across fandoms, whereas social networking sites like AiFaDian and Weibo are about the connections between people. In our Post-AO3 era, the unhappy migration of danmei to spaces dominated by OnlyFans logic or a suffocating iron fist results in a serious castration and sullying of the actual writing. They are no longer protagonists on centre stage. They are mere commodities, assets, tailored to the customer’s demands. More importantly, they are the stark emblems of a policed age. Struggling to choke out words is not a pretty look and fanfic writers know it.

They know it, they mock their knowing and they mock their comically pathetic attempts at resistance through absurdity.

It’s clear that the prime time for danmei on the Chinese web is over. Its exile from AO3 has resulted in a brutal form of survival escapism, changes so drastic that the genre is opaque, by design, to all but the most faithful.

Let’s talk about meal replacement.

“Meal replacements” (代餐) culture in the danmei community are emblematic of the trend I’m describing. The phrase is used literally: replacements for “real”, forbidden food. Since any representation of gay intimacy in any form will be instantly removed on the Chinese internet, fans consume other types of content to satisfy their appetite: cute animal videos that can be imaginatively anthropomorphized to reflect gay romance. Screenshots that can stand-in for common ship tropes of yearning and desire. Footage of a tiny, benign kitten playing around with a doting Alaskan doesn’t come off as suspicious in Big Brother Weibo’s surveying eyes:

The same goes with these two images:

Popular meal replacements would often include a back story about the animal’s personality, their previous interactions leading up to this captured moment, and additional lore:

There are Weibo accounts dedicated to scavenging the internet for meal replacement content ripe for anthropomorphization and appealing if anthropomorphized, like @代餐墙 and @代餐bot. People will then use the content as the mold, swap in their favourite gay couple, fantasize, and go from there.

Almost at any given moment, there will be someone who frequent male homoerotic content reposting videos like the one shown here with the snappy phrase “subbed subbed” (代了代了), indicating that they have substituted in whoever they were a fan of:

Yan: It seems that almost all the language around fanfic and shipping in Chinese is food related. To write fanfics is to make meals/produce food (做饭/产粮); to consume fanfics is to eat meals (吃饭); and to indulge in romantic interactions of your ship is to eat candy (磕糖). This might be how meal replacement got its name. If you’re desperate and hungry, anything will do.

Emily: Leaving aside the ethics of anthropomorphizing and subsequently sexualizing animal behaviours for a second, why is this happening in the first place?

The concept of “McDonaldization” might be useful here. I argue that Chinese danmei is becoming McDonaldized——beginning to operate on the principles of a fast-food restaurant.

Ritzer, who first defined the concept, lists four characteristics that constitute McDonaldization4 and one of them is especially noteworthy in our context: efficiency. Ritzer has a very specific definition of efficiency. In using the word, he is referring to the mindset in which minimization of time is always prioritised. In a fast-food restaurant like McDonald’s, consumers will go from hungry to full as fast as possible.

So what’s the deal with meal replacements? My tentative answer is that they are the most efficient way of consuming danmei. As with real-life meal replacements like protein bars and bio shakes, it’d fill you up nice and fast. Animal behaviours do not have the same level of complexities compared to humans. More often than not, they are action-based, physical and therefore carnal. Easy to consume, process and almost already vaguely suggestive, meal replacements are a “quick fix” of homoeroticism on the go. It is preferred over a time-consuming, elaborate 8 course dinner where the menu is all in French——an extended body of fiction with multiple chapters, character arcs and plotlines.

Ritzer’s 2019 article revisits this theory in the modern age. He asserts that “digitalization has served to intensify the process of McDonaldization5.” I would argue that meal replacements are, in some ways, propelled by the saturation of TikTok-ish endless information streams in recent years. We currently live in the day and age where delayed gratification is now only tolerated by a handful of people.

Jaime: this reminds me of this analysis about the desexualization of porn, the virality of image that make erotic image-forms more widely available (than text), and sex (in every day life) becoming consumer product except China lives in the future so we are replacing "human face" with "animal face": "Intercourse has ceased to be sexual, and signifiers once tied to sex are now just individual pieces in the “Lego set” of one’s identity, divorced from the context of a relationship, a scene, or even desire itself...The message isn’t one of unfettered, unchecked carnal desire; it’s one of endless, aimless consumption and dopamine hits…”

Emily: This article on TikTok and comedy makes a perceptive remark: TikTok created a new comedic genre consisting not of an incremental buildup and an explosive punchline, but only an “existential chuckle”, a “huh, that’s quite funny”-and-moving-on culture. The same goes with the consumption of danmei. Most want instant reward - instant turn-on, instant adrenaline rush, instant flash of the thoughts “that’s literally my ship” and “fuck, that’s hot and my ship is so real”. If that euphoria moment elapses, well, we can always swipe and watch the next one. The food (meal replacements) is readily accessible, easily digested and “organic” (uncensored), the preparation time (imaginative leap) is negligible, and the final sense of existential thrill is instantly evoked.

More importantly, meal replacements are opted for by will but also by a complete lack of choice. When the sign itself can’t exist, we are left to devour the signifiers and the signified. We are cornered to the point where meal replacements are becoming staples.

----

On 27th February 2022, a two-year old post from AO3’s now dormant Weibo account started recirculating. “We regret our inability to resolve what appears to be a sudden manual disconnection with AO3’s servers on the Chinese side,” it read.

This is our annual “cyber tomb-sweeping”, said comments on the reposts. Behind this digital vigil was both a profound mourning of the loss of creative freedom, and a resigned acceptance of a new normal. Because alongside danmei’s (unwilling) collusion with platform consumerism and its futile micro-rebellions against authoritarian control is a growing force: a grateful, tired embrace of the less-than-real.

Simon: Some aspects of this topic reminded me of… Bandcamp. The indie-friendly Oakland-based music platform was recently purchased by Epic Games, which Tencent owns a 40% share of. This could have lasting implications for Bandcamp’s future and potential attempts to delve into the Chinese market… but that’s perhaps best talked about another time (which I hope we can do!).

What’s interesting here specifically is how critics and commentators like Mat Dryhurst have discussed how a better endgame for Bandcamp might have been “exit to community”—community ownership of the platform removing the need for growth that led to the site’s sale. It seems like there are some analogies with the platforms hosting Chinese slash fiction: a small passion project of a website cannot, or does not want to, invest in censorship, and thus builds a community. But when founders realize the project can go legit and make money, or it reaches a critical level of popularity, things get cleaned up or blocked. Could collective platform ownership work here, or might it still require a legal figurehead who could face serious fines and jail time? The closed off environment of AiFaDian is an interesting workaround, and yet kind of frustrating. It makes me think about discussions with Krish on the model for cultural events in Delhi: things are going on, but mostly confined to semi-private spaces, where you need to know someone to gain access. Though developed as a protective strategy, I think this kind of platform elitism can prevent broader, more interesting conversations from happening.

Emily: Another Chinese slash platform that's gaining a lot of dedicated users is 废文网 (SoSad.Fun), the edgy name deriving from its self-awareness that, yes, we are living in a sad age of restricted creative freedom and the site itself may not last long before getting shut down. It’s also “censorship-free” (thanks to a server based abroad) but it is STRICTLY membership-only. The process of registering is deliberately cumbersome (it took me about a month). What makes registration easier is, as you've mentioned, through someone you know who's already on there with an invitation code. Otherwise, it's such a hassle. But fans say it's worth it, because apparently 废文 houses some of the best and most original danmei out there.

Krish: Chinese slash platforms are truly the private BitTorrent trackers of today (RIP What.cd)

Simon: Wow! Also, SoSad.Fun sounds like the name of an emo band from Hong Kong or Guangzhou.

Krish: Wayne’s SoSad.Fun

Aaron: More broadly, I think the platform elitism that we’re seeing develop with danmei communities is a mirror of how Chinese internet users engage with the global internet and open political discussion. If you’re savvy enough, accessing these with a VPN is hardly a problem, but most people probably wouldn’t even think to look for that access in the first place. And similar to the way that AiFaDian ends up gating content by your ability to pay, “savvy” VPN users are almost entirely made up of those from privileged classes – former international students, employees at multinational companies, foreigners, etc.

The insanely creative ways that shippers try to evade internet censorship also reminds me of more explicitly political attempts like the mass reposting of a censored 人物 Magazine article in different coded forms, or how demonstrators in Russia have started holding up blank signs to protest the country’s draconian post-invasion censorship. In these cases, though, I think the point of using codes is actually to draw attention to the censorship itself. With danmei, it looks like the point is to just stay under the radar and keep publishing. Learning the particular slang and codes of behavior is an integral part of joining any subculture, but this makes me wonder if there’s a point where finding danmei becomes so obtuse and involved that it walls off discovery for the next generation.

Krish: Outro music this week is also fan fiction, of sorts.

This amazing new No Nonsense Collective (無妄合作社) cover of a Karen Mok song makes the original ballad sound like a Car Seat Headrest B-Side.

This is part of a new 40th anniversary collection from Taiwan’s Rock Records, getting younger (cross-straits) bands like Sunset Rollercoaster, Carsick Cars, Elephant Gym, Default, Wayne’s SoSad.Fun and Mong Tong to cover old classics from their back catalogue. Worth a dive in.

Yan: See you next time!

BIOS:

Emily is secretly spying on Chinese fandom to turn everything into an essay. An ex-fan of Chaoyang Trap, she made a conscious effort to include Ting’s nisu piece in her dissertation without knowing that one day she’d be a proud contributor.

Yan is still recovering from the discovery that Hello Kitty is a little girl, and is now processing the fact that her favourite meme character My Melody is Hello Kitty’s best friend.

Krish would like everyone to know that, in craft beer lingo, there is something called a “cool ship” that produces extra funky brews.

Simon has a lot of music in his Bandcamp wishlist.

Aaron is having a lot of trouble imagining how the friendship between Hello Kitty and My Melody would work.

Yi-Ling is missing Chaoyang & her Chaoyang ppl.

Jaime is still trapped in Chaoyang. The rest of Chaoyang Trap is on holiday. 😭

ACGx (2018) “有人做了个‘爱发电’的网站,问了他3个问题”. Wechat Subscription account. Accessed at: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/sFDaj-WjviK0WDMfcfEB1Q

Ibid.

Noveck, B.S. (2000) ‘Paradoxical partners: Electronic communication and electronic democracy’, Democratization, 7(1), pp. 18–35. doi:10.1080/13510340008403643.

Ritzer, George (2013) The McDonaldization of Society: The 20th Anniversary Edition. SAGE.

Ritzer, G. and Miles, S. (2019) ‘The changing nature of consumption and the intensification of McDonaldization in the digital age’, Journal of Consumer Culture, 19(1), pp. 3–20. doi: 10.1177/1469540518818628.