Rewilding #4: Society of the Scalper

An evolving dictionary of the Chinese web: train ticket hacks + Judith Butler voices + DdoS as method + the huangniu inside us all

In the house this week: Yan, Krish, Emily, ████, Simon, Caiwei, Henry, Tianyu, and Yi-Ling.

Krish: Welcome back to Chaoyang Trap, the newsletter that separates the Group from the Chat in a new story form we call the Trap. We’re back from our “summer” “break” to wrap up Season 2 and 摆烂 for good.

This is the closing edition of Rewilding, our series of explorations into the language of the Chinese internet.

In each issue, we pick a word from the labyrinthine swamp of online life in China, lay it on the table, scrutinize it and take it apart in the form of a mini-essay, then replant the pieces, sowing seeds for further conversation. Rewilding queen Yi-Ling is on book leave, so this might be more…free-form than usual.

Previous editions of Rewilding have looked at boundary balls, cut chives, and flying pigs. For this final trip, we’re grabbing some tickets.

抢: “Qiang” Culture, or Why Meritocracy is a Scam

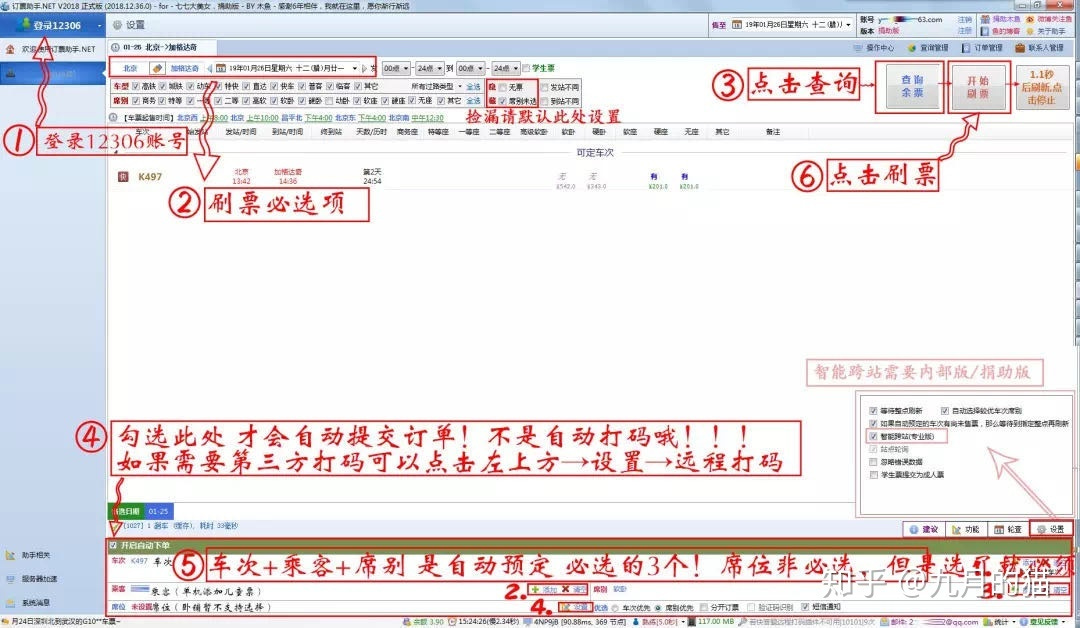

Krish: It's 2015. Spring Festival is approaching and you need to buy train tickets to go home. New browsers come bundled with a plugin that lets you cut the “queue” when booking online. The plugin causes Github servers to crash globally.

It’s 2018. The Beijing Film Festival opens next week and you want to watch the special midnight screening of Titanic. Tickets are sold out in seconds, then resold by scalpers for 10x the price.

It's 2020. You want one of the 2000 daily slots allowing you to cross the border into Hong Kong. You pay for a service on Taobao that will qiang slots the second they're available, and hand them over to you.

It's 2021. You need to take the TOEFL exam to be able to go to university in the fall. Competition to book exam timings is fierce. You’ve got plugins, fixers and scalpers on call. But so does everyone else.

What connects these situations is “qiang” (抢) culture, a pervasive organising principle of the Chinese web.

The word “qiang” means "to grab" or "to seize." It’s about optimally getting in early on something, to be first in line. It’s a mental state of permanent readiness. A mindset, to borrow a recent Douglas Rushkoff phrase. Perhaps THE Mindset of the terminally online in China.

Yan: Qiang is a social act. It does not exist in the singular, it only exists in the social. One “qiangs” to compete against imagined others. Without a…mobilised mob, there’s no need for qiang. However, sometimes it is precisely the collective enactment of qiang that creates the mob: think about the crazy long lines outside a wanghong milk tea shop.

Krish: To qiang something—tickets, slots, deals, seats—is to lay the groundwork to be first in line, the accrual of small advantages and beneficial knowledge to give you an edge. It’s to steel oneself for a gold rush, but also to disavow any moral quandaries about getting ahead.

Plugins to cut queues, scrapers to find openings—that’s allowed, even expected. Qiang culture normalises behaviours such as writing code to surveill, DDoS, and grab first-come-first-serve digital listings, or creating ghost accounts to increase chances in online lotteries.

To qiang isn’t to steal or pirate, though. The scarcity that makes this mindset necessary is usually not directly challenged. Qiang undermines the queue while simultaneously defending its existence. To paraphrase Rushkoff, It allows for a kind of “externalisation of harm” to others, sometimes enabling an ease of distance from the people and places that are compromised.

We make a lot of videogame speedrunning references here on Chaoyang Trap, and it comes from a genuine belief that speedrun culture offers some pretty insightful lenses to look at online life in China. Qiang culture is pure speedrunning: an attempt to optimise routes through bureaucracy that nonetheless respects its boundaries. If you’ll excuse the analogy, qiang is an “Any% No Major Skips” run through life, one that’s okay with tool-assists and sequence breaking, but not with going out-of-bounds.

████: I think the Shanghai lockdown earlier this year really drove home the realities of artificial scarcity and online qiang culture for a lot of people, especially those that found themselves unable to compete for food effectively (like my elderly neighbors.) I know some people can find it exciting when it’s for film festival tickets, but it is pretty fucking miserable to wake up and unsuccessfully qiang for food every day. I was heartened to see people challenge it over time, and begin to exploit qiang strategies for the benefit of their neighbors—Rushkoff is right in a lot of ways, but it gets a lot harder when you’re externalising to somebody you share a stairwell with.

Krish: Also, an *expectation* that people will qiang any scarce goods on the Chinese web colours how many platforms and processes work here. It’s why friction is common in Chinese UX practices, why inconvenience is imposed on everyone as defence against qiang-like behaviours by the few. Keller Easterling calls this a “chemistry of causation”, and qiang culture permeates how systems are designed, how scarcity is always baked in, how shortcut-seeking networked habits are formed.

I feel like qiang normalises the logic of scarcity even in abundance, through creating a collective experience of individual gain. It’s a foreclosure of community: in many settings where you’d expect to see mutual aid, you get competitive qiang culture instead.

Caiwei: As the dread of Zero Covid is prolonged, are we going to see more acts of "qiang" both in the way of getting ahead against manufactured friction, and the mob-like acts of complete chaos that we saw in quarantine zones? Behind qiang is a sense of deprivation and lack of security, and in this sense qiang mentality could both be the source and the result of precarious living conditions.

Krish: Exactly. Qiang is one reason why policies of artificial scarcity in China are politically possible. The response to designed inequality isn't questioning the lack, but rather a readiness to qiang.

Yi-Ling: Curious about how marketing tactics & user behaviour during, say, Black Friday might differ from that during Singles’ Day. What are the different cultural triggers that might induce a scarcity mindset in two of the most aggressively consumption-driven marketplaces in the world? To what extent is a “scarcity” mindset more present in the mindset of Chinese consumers, simply because that experience was a part of recent history?

Simon: In terms of its more cultural/entertainment-based applications, I guess qiang is one of a number of interfaces between online culture and IRL, a moment of frenzied online activity that may translate into an exclusive offline experience that once again translates into online social capital, like the charged energy of a wanghong site in the wild. To put it another way, I’ve never even tried to qiang Beijing Film Festival tickets, but I certainly have seen a lot of people sharing screenshots of their tickets!

This article in the Atlantic about the craze for restaurant reservations in America quotes cultural critic W. David Marx to discuss how, when access to the accoutrements of a hip, cultured lifestyle has become more accessible than ever before, the ability to grab a finite resource (i.e. seats in a restaurant) can become an increasingly important symbol of status and cool. I feel like in China right now, status symbol restaurants are more likely to be accessed through queuing than months-ahead reservations (perhaps this is different in loftier reaches of the upper class), but this did strike me as a case where Chinese and Western online cultures are spinning out in occasionally intersecting loops, perhaps more in sync than is commonly thought.

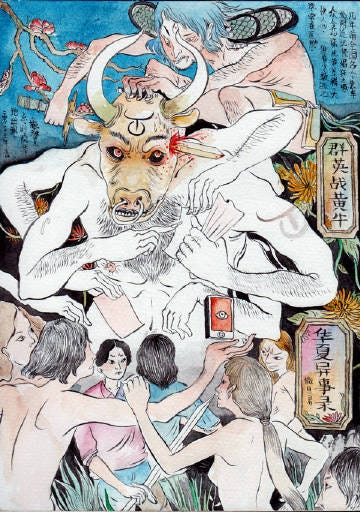

Yan: Yes, “qiang” is not created by or limited to the online. Before we could make online doctor appointments, people had to go to hospitals early in the morning (I’m talking 4 or 5 AM) to stand in line so they could qiang an appointment when the hospitals opened at 8AM. This may be the origin of scalper/huangniu culture, where people hoard scarce appointments with popular doctors and resell them for a higher price.

Tianyu: In a way, qiang culture emerges from this question of “how do you distribute resources that are so scarce to a population of so many people?” Before Dengism, the solution was some form of hierarchy-enabled egalitarianism, where everyone supposedly received their shares through work units—the danwei gave you canteen access, housing options, and film tickets, and rice packets. The message of neoliberalism in the PRC was that if you worked hard enough, you’d eventually climb up the ladders—getting into a college, buying a house, and visiting parents in the countryside during the Spring Festival. But the problem with scarcity remains: demand is now higher, and supply hasn’t kept up. We came up with new forms of distribution, but all seem unfair and arbitrary; even university slots, for instance, are assigned by provinces.

[Content Warning: blood, violence]

Krish: Even when these underlying interplays move online, this perception of scarcity persists.

Yan: Yes, though “qiang” online is completely different from offline. To qiang online is to compete with an invisible crowd (maybe this is also why people don’t have moral burdens as Krish mentioned above). It seems to me that “first come first serve” is the basis for everything that can be qiang-ed. Many online qiang scenarios come with interfaces, visual elements and effects that reinforce the symbols of scarcity: countdowns, stock numbers going down fast, being stuck between the product page and the purchase page… They induce the adrenaline rush that comes with being competitive, but there’s also uncertainty: you don’t know how many people you’re competing against, and therefore can’t even evaluate your chances, which justifies the over-aggressiveness in qiang.

Krish: An aggression that’s so normalized that it can even be reliably deployed in service of more progressive ends. In January 2020, A group of music fans used a “buy now” qiang spectacle to generate interest for their mutual aid campaign to source PPEs for people in Wuhan:

Henry: The example above is so interesting, and feels like it overlaps with Gofundme in that particular, socialize-risk-but-through-entrepreneurial-self-marketing-campaign, way. Trying to think of other ways that egoism is strategically deployed to get the Chinese population to do...progressive (?) things; reappropriating "qiang" in the way that "we don't take too kindly to———bigotry in these parts" reappropriates xenophobia. Is there a form or even formality of qiang that can be separated from its (ostensibly neoliberal) content?

Yan: For the most part though, Qiang is also the reason for manufactured scarcity, which is used to create far more cynical marketing campaigns or shopping sprees. I’m thinking of designer sneakers, or Li Jiaqi’s live streaming show. Manufactured scarcity makes “qiang” a spectacle to draw more people in, turning spectators into consumers.

Yi-Ling: I wonder to what extent the virtual qiang is the successor of virtual weiguan. Back in the heady optimistic days of the Wenzhou train accident in 2011, the talk of the town was that weiguan—or collective observing—would change China. (Change meaning liberalization.) One could say now that instead, qiang has changed the Chinese internet. (Change meaning commodification.) Instead of serving as a digital town square where one could freely participate in all kinds of different ideas in the public discourse—the louder your voice the better—it’s become more of a digital hawker’s market, where one can freely consume all kinds of goods available in the public marketplace—the faster your wallet hands the better.

Tianyu: This reminds me of qiang shafa as an early form of online engagement in China. The phrase, which literally translates to “grab the sofa,” means to leave the first comment—usually just the word “sofa,” without additional context—under a new post on an online message board. (This was common in the 2000s; nobody does it anymore.) Shaohua Guo traces the lineage from qiang shafa, in which she observes “an inclination toward voyeurism and exhibitionism,” to weiguan—the overarching idea is what Guo calls “digital witnessing.” To bear witness online might be performative activism at best; but the costs of change are just too high, its prospects too distant.

Emily: Qiang spectacles occur on a daily basis in media and entertainment. Like Yan said, nowadays M&E giants manufacture scarcity of concert or event tickets by “locking” seats to create a false sense of popularity. Sometimes, this pseudo-hype is slapped on the celebrity as a badge of honour, so that the company can boast about their artist’s clout. At other times, qiang spectacles can be manufactured to directly generate profit. The most extreme case is probably Time Fengjun Entertainment and their boy group TNT.

TF Ent hosted an auction in 2020 where they’d only sell concert tickets to the top 100 highest bidding fans. The winner purchased the ticket at the price of 21,312 RMB. That’s almost the price of a can of Coca Cola (not Pepsi) during the Shanghai lockdown. It is also alleged that M&E companies hire scalpers to work for them. Scalpers then qiang seats using bots and algorithms, resell to fans at a higher price and perhaps split the earnings with the company. In both scenarios, fans often willingly collude with this kind of corporate manipulation because they either buy their way in and proudly display their loyalty (affluence), or sulk (brag) about how their idol is too popular for them to reach. Fans feel like they must participate in qiang, because everyone else is doing it and if I need to be approved as an authentic fan, I must be a winner amongst them.

The tension that lies behind qiang is this bizarre push-pull of conformity and self-centeredness: I must qiang like everybody else and yet be ahead of everybody else.

████: My suspicion is that there’s more questioning of the underlying conditions that lead to this competition than you might guess, but with so few avenues to address them, there’s little else for most people to do than qiang themselves.

Krish: Just wanted to remind everyone that this legendary headline exists, and was caused by qiang culture.

Tianyu: That’s it for this episode. Thanks for reading, and for bearing with us through our summer break. We’re going to keep paid subscriptions paused while we figure out a more regular schedule.

Krish: Outro music this week is “Agora Bar” by Beijing (but not Chaoyang) band Sleeping Dogs. Agora is a dive-bar-cum-Indian-restaurant that was a regular haunt for at least one Chaoyang Trap member. They make good mixtapes.

For more China music in this vein, remember to subscribe to Chaoyang Trap friend Jake Newby’s Concrete Avalanche. We have two episodes left before the end of Season 2. See you all next time!

Tianyu: Bye!

Krish collects business cards from scalpers. He tries to qiang ideas from his own mind before they disappear.

Yan is plotting the start of the academic discipline of qiang studies.

Tianyu thanks qiang culture for teaching him how to make Chrome extensions.

Caiwei recently enjoys qianging pre-owned clothing and accessories on Ebay.

Emily was lowkey hooked on Li Jiaqi because one of the models he hired to hype up his qiang-driven live streams is insanely good-looking.

Simon convinced himself early on that many qiang systems would not work without a Chinese ID, and therefore tries to lead a qiangnostic lifestyle.

Henry has never successfully qiang’ed a ticket; he also gets cut in line a lot.

████ became an expert on grocery delivery platform qiang strategies the hard way.

Yi-Ling is writing a book. She’s also down with a fever & unsure if it’s an allergic reaction to antibiotics of the new standing committee line-up.